Catholic church leaders have often demonstrated a particular antagonism towards Australia’s leading minor party, the Greens. Are there any consequences from this for either the church or the party or is it a minor matter? Both major parties still prefer to have the church onside, despite its numerical decline and declining credibility following institutional child sexual abuse. But the Greens may not worry. Younger Catholics also probably care very little what their church leaders say.

The antagonism exists at both federal and state level. The relationship is currently on display as the federal parliament moves again towards anti-discrimination and freedom of religion legislation. Archbishops Anthony Fisher (Sydney) and Peter Comensoli (Melbourne) have joined the National Catholic Education Commission and some other religious leaders in rejecting a role for the Greens in matters concerning religious schools.

Criticism of the Greens by some church leaders has quite a long history, though there have also been priests and heads of church agencies who have defended the party on occasions against charges of being anti-Christian.

The most notable attacks have come from former Archbishop of Sydney, Cardinal George Pell. Prior to the 2010 federal election Pell was critical of the Greens in concert with the conservative Australian Christian Lobby. He addressed the attractiveness of the Greens’ environmental policies by saying that they were impractical and hurtful to the poor. Going much further he condemned the party as anti-Christian and opposed to the notion of family. In fact, Pell said, for those who value our present way of life, the Greens were “sweet camouflaged poison”.

Greens leader Senator Bob Brown provocatively defended his party as more Christian than the cardinal, hitting back by claiming that Pell was out of touch not just with Australian society but with many Catholics too. Fr Frank Brennan thought Pell’s language was unfortunate and he called for a more dignified distance and reticence from church leaders.

The bad blood between Pell and the Greens never dissipated and was revived in 2017 when, in the middle of legal claims against the Cardinal, the Senate passed a Greens motion to call for Pell to return to Australia. In rebuttal Pell described the Greens as having an anti-religion agenda.

After Scott Morrison’s government failed dismally to find a successful formula for religious freedom/anti-discrimination legislation between 2019 and 2022, the Albanese Opposition made a 2022 federal election promise to do so. Now, as the federal government considers an Australian Law Reform Commission paper on anti-discrimination and religious protection, Archbishops Fisher and Comensoli have urged Prime Minister Albanese to seek bipartisanship with the Opposition rather than to negotiate with the Greens to build a parliamentary majority. While the Opposition Leader has already rejected Albanese’s offer of bipartisanship before proceeding, the archbishops in an Open Letter from 41 religious leaders described the Opposition’s position as “reasonable and prudent”.

Albanese flagged another way and broached in Cabinet the possibility of working with the Greens “if the Greens are willing to support the rights of people to practice their faith”. CathNews then reported that “Catholics say discrimination reform backed by Greens ‘dangerous’”, while the story in the Catholic Weekly was headlined, “Faith leaders urge PM: Don’t deal with Greens on religious schools”. The National Catholic Education Commission added that a positive agreement was unlikely because “the Greens are ideologically opposed to religious schools”.

The issue of religious freedom/anti-discrimination is a wickedly difficult balance to strike and, if unresolved, will be made into a major federal election issue next year by certain religious leaders, including Catholics. Does this matter? Labor’s promise was unwise given Morrison’s failure and the divisiveness of the issue. If the Albanese government is judged to have failed to implement an election promise, however, then it could swing some voters against Labor. It is unlikely to hurt the Greens though as they rely less on so-called religious voters.

How the Church’s political interventions will be judged is another matter. Despite its past support for the breakaway Democratic Labour Party, the Catholic Church is now locked into the major parties, and more sympathetic to the Coalition than it once was. Major party sympathisers, Labor and Liberal, are common in church education bureaucracies at the national and state level.

Being locked into the major parties leads to more conservative outcomes than if the Greens and other crossbenchers are involved. The ‘balance’ will be struck further towards the conservative end of the political spectrum because the defeat of Liberal moderates by the six Teal Independents at the last election means the remaining Liberals are more conservative. One third of voters did not support the major parties in 2022, either Labor or the Coalition.

Such an outcome would consolidate the present conservative image of the church. The Greens should not be taken lightly, however, even if the church being dismissive of the most secular of the four biggest political parties might seem predictable. At the 2022 federal election the Greens won about 12% of the primary vote and about two million primary votes. Its pro-environment, pro-refugee and pro-renter agenda was especially attractive to urban voters. They gained three new House of Representative seats in Brisbane (making four in all) and now hold eleven Senate seats. Surveys regularly show higher support among younger voters for the Greens. It is highly likely that many Catholics, especially younger Catholics, and particularly young Catholic women, voted Green.

Both the Church and the political parties have a common interest in increasing the adherence of young people. Church attendance among young Catholics is spectacularly absent. But the Greens have always done well. Even a June 2023 paper from the conservative Centre for Independent Studies by Matthew Taylor was titled “Generation Left: young voters are deserting the right”. The environment was the top issue for voters under 24 and the Greens score highly on that issue. In the 2022 federal election the four seats with the highest proportion of young voters (aged 18-29) were won by the Greens: Melbourne, Brisbane, Griffith (Qld) and Ryan (Qld).

px.jpg)

Church leaders should only initiate a bitter political dispute at the next federal election about religious freedom/anti-discrimination with their eyes open for its potential adverse consequences for the future of their church. Such an approach might alienate young Catholics even further. At the very least younger Catholics, including older secondary school students and recent graduates, should be consulted about their views. Otherwise, the Church is flying blind.

John Warhurst is an Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University.

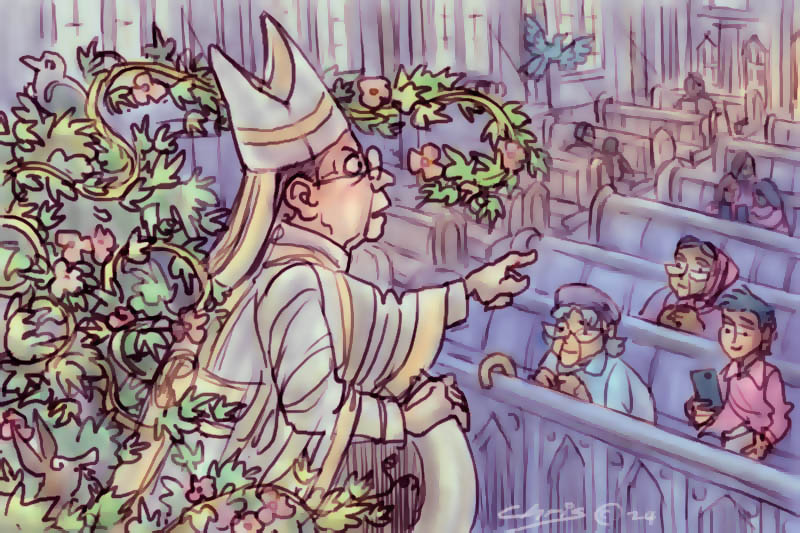

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration