It hits you the moment you wish to pay for something. First, there is the issue of online payment. The company offering the product not only prefers it but demands it. There are no humans at the end of the line to receive calls, merely a digital menu with a tin voice of dry options (‘To inquire about your account, press 1’).

Absent is the tangible feel for cash, something that began with the introduction of plastic cards. It also eliminates the reassuring face over the counter, the individual at the checkout who counts your money and returns your change. There are no sheets to feel, no satisfactory placing of notes into a wallet. In its stead comes the digital form, an incoherent, intangible object that only exists on trust, on conjured, industrial magic. And the device to facilitate this is the smartphone.

Inserting the smartphone into such dull transactions has become the norm. Many online payments now require an additional authentication service. This entails messaging a code to your phone to validate the transfer. No phone, no code. No code, no transaction. This very fact partitions users and members of the community: you are either on board in the digital marketplace, or you quietly vanish.

This tendency is totalitarian in that it totalises the entire field of transactions. It abolishes choice. It removes the means of paying with good tender through a fantastic means that we have all willed into existence. It also exacts obedience from users while proclaiming convenience.

Beyond such transactions lie the broader problems of smartphone wizardry. Conversations are impossible to have without resorting to the small screen. Social interaction is lubricated by the dulling effects of phone use. University students turn up to class without pen, paper or even a laptop, preferring to use the phone to record the lecture or transcribe the notes. (Note taking, in that regard, is a rapidly dying art.)

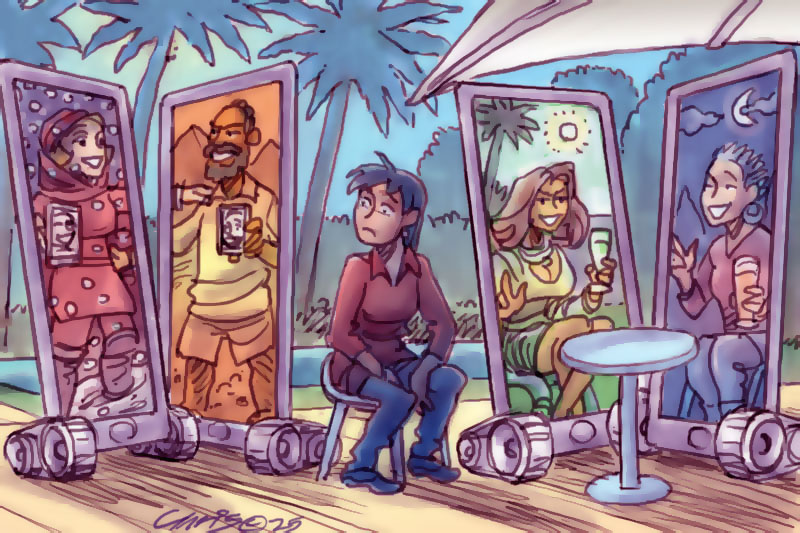

For those who dislike phones and are vexed by having the internet in their pocket and at hand on a permanent basis, any situation is not only exceedingly difficult but ensures they will be seen as luddite, cantankerous and eccentric. Cunning methods of subverting this can involve the use of temporary phones or the established accounts of other users. One’s mother is more likely than not to have a more advanced phone, for instance, or the tech savvy spouse who cannot do without. Both can provide useful substitutes. But this merely confirms the estrangement, the isolation, the debarring of those who would rather wish for alternatives.

The pervasiveness of smartphone usage has even befuddled policymakers. The United Nations’ education, science and culture agency (UNESCO), for instance, has taken a special interest in the way students are using smartphones in class. By the end of the year, the agency noted that 60 education systems across the globe had implemented bans on the use of smartphones in schools. By the end 2024, a further 19 systems had been added.

'Smartphones are unlikely to vanish any time soon, but accommodating alternative means is surely not something to be ignored.'

The thrust behind such bans lies in the question of whether smartphone use aids pedagogical pursuits, though issues of cyberbullying and wellbeing also figure. Ironically enough, students find themselves in a vicious cycle, requiring their device to cope with the very anxiety and stress that might be caused by excessive use. The genius of the smartphone is that it dictates its own necessities.

The effect of such bans, in any case, is questionable. Efforts to enforce outright bans in Canada proved impossible, resulting in their revocation. A ban in New York City did not last the distance, largely for concerns that parents were being frustrated in maintaining contact with their children. The smartphone, it would seem, outwitted them all.

To see this as a problem confined to a certain demographic is also convenient. Adults do not fare much better. Broadly speaking, those keen to study the effects of smartphone use have found that abstinence or reduced use is not to be sneered at. An ‘experimental intervention study’ published in 2022 found that reducing incidents of smartphone usage for one week improved the quality of people’s lives. ‘Programs that focus on the increase of well-being and a healthier lifestyle,’ argue the authors, ‘could benefit from the integration of controlled reduction of smartphone use.’

When Edward Snowden, former contractor of the National Security Agency, revealed the indiscriminate surveillance by that body of US citizens and US allies, various responses were floated. German Christian Democratic politician Patrick Sensburg, for instance, suggested that typewriters might be used, ‘and not electronic models either’. While dismissed as absurd in various circles, the idea has a smidgen of plausibility.

A modern guerilla manual, a counter-revolutionary program that offers some redemption from this elaborate, global tyranny of imposed technology, is required. And tyranny it is, for it takes that fundamental choice with which we engage fellow members of society. Smartphones are unlikely to vanish any time soon, but accommodating alternative means is surely not something to be ignored.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.