The most important days are often mark the most seemingly lost causes. Anzac Day, for example. The United Nations International Day of Peace on September 21 is also celebrated at a time when people are increasingly killed and driven from their homes by war and violence sponsored by other powers. Political scientists warn that these conflicts may well develop into a wider war. At the same time Australians are confronting the extent of domestic violence in society and the threat of militant groups bonded by hatred for other groups. The theme of the International Day of Peace – Cultivating a Culture of Peace – has never seemed more desirable. Yet the times and populist comment argue against it. Even people who demand an end to the massive killing of children and displacement of people in Gaza are criticised for naivety. Their critics argue that the only way to secure peace is to support those who make war.

In that context, the theme of the International Day for Non-Violence in early October is worth pondering. It argues that ‘There is no way to peace. Peace is the way’. This undercuts the argument that peace can be guaranteed only by fighting for it and so by amassing and deploying more sophisticated weapons than one’s adversaries. It also makes us ask how appropriate it is to call occupying military troops a peace force. In Northern Ireland and elsewhere they have often intensified and embittered conflict. The theme pushes us to focus on the human heart as the place where peace is made. It also insists that we call out the peace-making pretentions of violence for the illusion that they are.

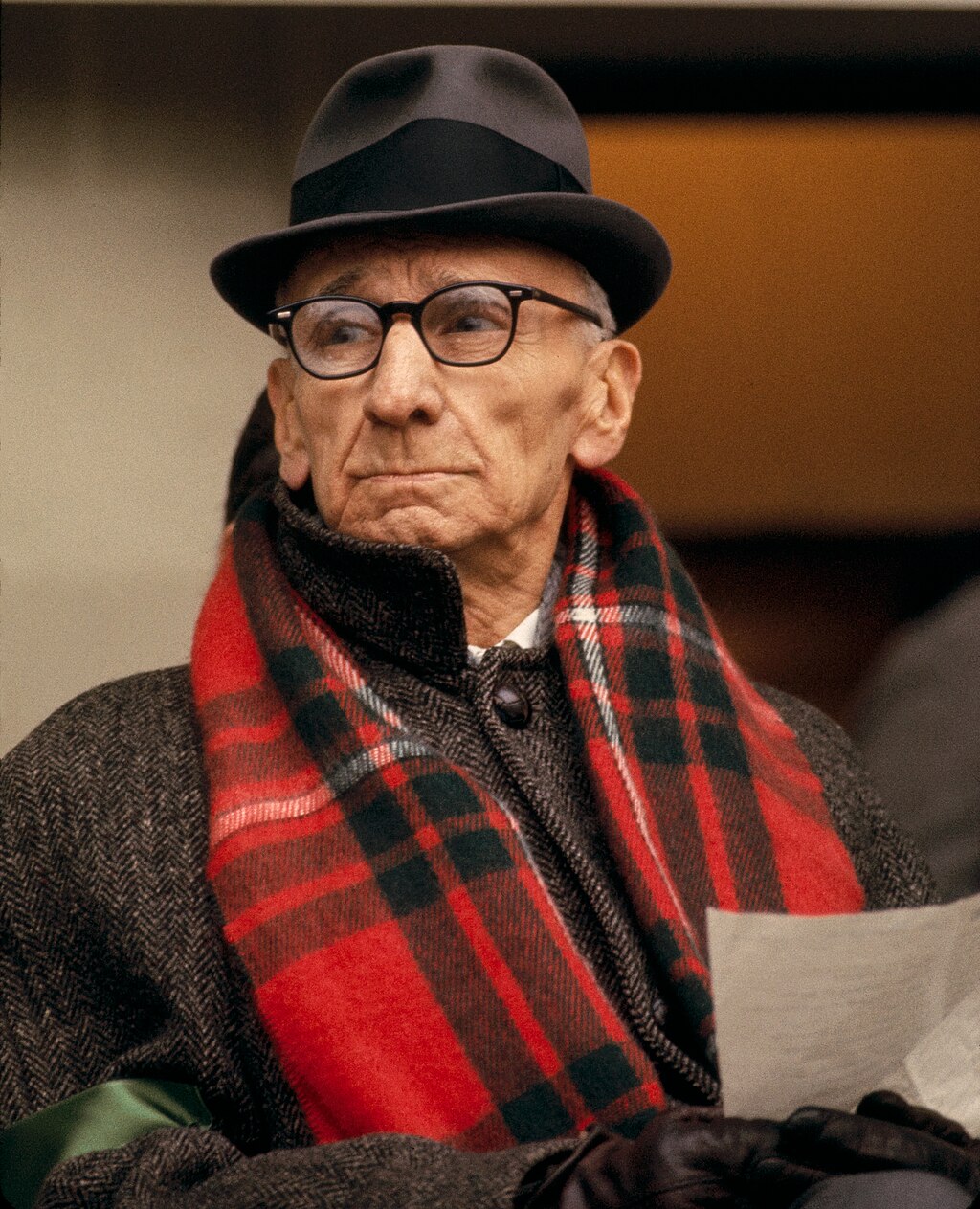

The life of the man who provided us with the theme embodied its double demand. Though little known in Australia, Abraham Johannes (A.J.) Muste spent his life commending pacifism and leading movements to make the world more just. As a young child in 1895 he migrated to the United States with his family from Holland. He first taught in schools, and in1909 became a Minister in the Dutch Reformed Church in Washington. In his studies he was influenced by the Social Gospel movement. His congregation was socially conservative, and he left it to become a pastor in the Congregational Church in 1915. His pacifism, however, alienated many in his congregation, and he resigned when the United States entered the war. As a pacifist, he became increasingly isolated in his Congregation, resigned, and became a minister in the Quakers.

The following year, he helped to lead a strike and organise relief for unpaid workers’ families in textile mills which exploited their largely immigrant employees. When joining other workers on the picket line he was clubbed and gaoled, but when the police armed themselves with machine guns, he encouraged the strikers to radical non-violence. The strike eventually led to negotiation that improved the workers’ conditions. Muste became Secretary of the newly formed Textile Workers Union, and for the next fourteen years was a leader in the Labor movement.

In 1936, he resigned from his political role and gave his time to pacifism as a theological teacher of a radical but non-Marxist account of Christian faith. He became Director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation which arose out of the Social Gospel movement and influenced many leaders in the civil rights movement. He opposed McCarthy’s program out of concern for human liberties and was accused of being a Communist, led opposition to the War in Vietnam, and visited Hanoi with other activists opposed to the War.

Even this summary of a life that flowed easily across Institutions but which was rock solid in its costly commitment to the guiding principles enfleshed his claim that there is no way to peace, but that peace is the way. It certainly does not commend to later hearers a despairing withdrawal from public activity. It took A.J. Muste into situations of conflict often caused by rejection of his commitment to justice and to peace. But that conflict never led him to justify violence of any kind as a means to peace. He readily left institutions that accepted violence as a means to peace but found friendship through association with others, including Dorothy Day with whom he shared a radical pacifism, opposition both to Marxism and Capitalism, and courage in the face of hostility.

His commitments may still seem extreme to many today. But will anything more mild address the threats facing the world from violence, inequality and apathy?

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

Main image: A.J. Muste (Wikimedia Commons)