The following text is from Frank Brennan's address at the Transformation and Empowerment Symposium marking 50 years of the Signadou campus of ACU, 22 March 2013.

Last weekend at my regular parish mass in Canberra, I greeted the congregation with these words, 'Good evening. My name is Frank and I am a Jesuit. I've had a good week. I hope you have too.' I have been overwhelmed by the positive response by all sorts of people to the election of the first Jesuit pope. I have happily received the congratulations without quite knowing what to do with them, nor what I did to deserve them! Even at the masses at the Canberra prison last Sunday, prisoners were expressing their delight at what they saw of this new pope on the television. Perhaps this new pope's manner and mode of communication hold a key for us wanting to provide transformation and empowerment in the public square, and in the hearts and minds of all people of good will.

On Sunday, Pope Francis ended his address to the journalists in Rome with a blessing with a difference. He said:

I told you I was cordially imparting my blessing. Since many of you are not members of the Catholic Church, and others are not believers, I cordially give this blessing silently, to each of you, respecting the conscience of each, but in the knowledge that each of you is a child of God. May God bless you!

Respect for the conscience of every person, regardless of their religious beliefs; silence in the face of difference; affirmation of the dignity and blessedness of every person; offering, not coercing; suggesting, not dictating; leaving room for gracious acceptance. These are all good pointers for those of us dedicated to transformation of church and society and empowerment of all including the poorest and most marginalised.

On hearing this blessing from our new pope, I recalled the declaration of resignation of our previous pope. Just a month ago, Benedict announced that 'having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry'. He noted the strengths and gifts needed to discharge the office 'in today's world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith'. Having recognized his 'incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry entrusted' to him, he renounced it 'with full freedom'. Freedom, conscience, change, and demands exceeding capacities — these all played a role in a man of profound faith deciding that he could no longer discharge an office to which he had committed himself for life. He had the humility to admit the need for change.

Change is upon us as a Church. It is a moment when we are all feeling transformed and empowered. Just recall the scene when the new pope emerged on the Vatican balcony the other night. He appeared with none of the papal trimmings of office on his plain white robe. He commenced with silence, followed by a simple 'Good evening', and then, God help us, a joke about his brother Cardinals having gone to the other end of the earth to find a Bishop of Rome. He asked everyone to pray for his predecessor Benedict. But not once did he refer to the papacy, the Petrine Office, or the pope. He deliberately referred to Benedict as 'our Bishop Emeritus'. He spoke of 'the Church of Rome which presides in charity over all the Churches'. He spoke of the 'journey of fraternity, of love, of trust among us'.

He offered the simple prayers known to all Catholics: the Our Father, the Hail Mary and the Glory Be. The accompanying Monsignor was keen that he don the papal stole before offering any prayer. The stole remained in the good Monsigdnor's hands. Then the Pope asked the people a favour: 'I ask you to pray to the Lord that he will bless me: the prayer of the people asking the blessing for their Bishop. Let us make, in silence, this prayer: your prayer over me.' You could hear a pin drop in that crowd of 100,000 by candlelight. This was a Copernican revolution for the hierarchical Roman Church. Only after receiving the people's blessing did the Pope don the stole and proclaim the formal papal blessing. Immediately, he then removed the stole. The surrounding Cardinals thought the paraliturgy now complete. But no, the pope called again for the microphone. There was an embarrassed flurry of activity as they retrieved the microphone and turned on the sound system again. He returned to the familiar way of conversation with which he started the proceedings: 'Brothers and sisters, I leave you now. Thank you for your welcome. Pray for me and until we meet again. We will see each other soon. Tomorrow I wish to go and pray to Our Lady, that she may watch over all of Rome. Good night and sleep well!'

It was the Jesuit educated Dominican bishop Anthony Fisher who reminded us that the pope's white cassock is a derivative of the Dominican habit worn by Pius V in the 16th century thereby transforming papal dress for five centuries. Who would have thought that a twenty first century Jesuit wearing a derivative of a Dominican habit while eschewing other pieces of ecclesiastical paraphernalia could send such a clear message of transformation of the institutional church and empowerment for the poor?

Could not something of this new papal style help us to engage more creatively with our fellow believers and with our fellow citizens as we seek to bring good news to the poor, transforming our mode of engagement between Church and civil society, and empowering the poor and the marginalised? We come not only with authoritative teaching but with an attentive eye and ear to the experience of the people and their reflection on that experience.

In his homily for the Inauguration Mass on Tuesday, the feast of St Joseph, Pope Francis said:

Being protectors, then, also means keeping watch over our emotions, over our hearts, because they are the seat of good and evil intentions: intentions that build up and tear down! We must not be afraid of goodness or even tenderness!

Here I would add one more thing: caring, protecting, demands goodness, it calls for a certain tenderness. In the Gospels, Saint Joseph appears as a strong and courageous man, a working man, yet in his heart we see great tenderness, which is not the virtue of the weak but rather a sign of strength of spirit and a capacity for concern, for compassion, for genuine openness to others, for love. We must not be afraid of goodness, of tenderness!

'We must not be afraid of goodness or even tenderness!' As people of faith, we have the confidence that goodness and tenderness are prime tools for effecting transformation and empowerment.

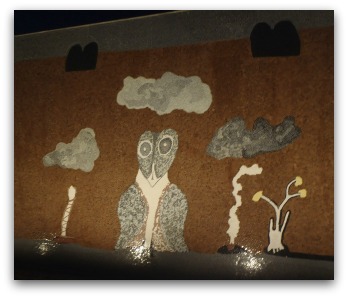

The photo accompanying this piece is the splendid mosaic at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture entitled The Holy Spirit in this Land by the late Hector Jandany from Warmun Community at Turkey Creek in the Kimberley. Hector was encouraged to paint in his home community by the Josephite sisters who had established a spirituality centre nearby. They also ran the community school and assisted at the old people's home. The sisters were not trained anthropologists or art advisers. Like Mary MacKillop they came amongst the poor in a remote area, shared what they had, educating the children and encouraging the adults. They were transformers and empowerers. None of the sisters would claim any of the credit for the art of Hector and his school of Turkey Creek painters. But for the sisters' presence at Warmun all those years, I doubt that Hector's paintings would now be hanging in the National Gallery. But for the selfless dedication of the sisters all these years throughout Australia, I doubt that there would have been 8,000 Australians in St Peter's Square three years ago attesting the holiness of Mary Mackillop.

Years ago, I met with a fringe dwelling group of Aborigines from Mantaka near Kuranda in North Queensland. They were squatted beside the Barron River. Across the river was a multi million dollar weekender built by a Melbourne businessman who used to bring his family in by helicopter. At the end of the meeting, the Aboriginal woman who convened the meeting pointed across the river and told me about the house and its occupants. On the roof was 'a helipad' — a new word for the traditional owners in that part of Australia. I later told the story at a school priding itself on providing an education for justice. The Year 12 boys asked all sorts of prying questions about the Aborigines and I was unable to give them satisfactory answers. They asked, 'If Aborigines want houses, why don't they build them for themselves?', 'What are they complaining about? If the white man did not come, they would not even have a water supply?', 'What's wrong with the businessman having a holiday house? Afterall, if he did not earn a lot of money and pay his taxes, we would not be able to pay Aborigines for welfare?' In the end, I simply asked them one question in return, 'Which side of the river are you standing on as you ask your questions?' Can you see that there are just as many unanswerable questions that you can ask from the other side of the river? Mind you, they are very different questions. They are the questions which can help us to transform our social reality and empower those on the other side of the river.

We need to be able to cross to the other side of the river, asking each other for help and offering each other the water of life. We can build the bridges that allow us to experience the reality on either side of the river, affirming that there is a time and a season for everything under heaven.

We don't need to look overseas or up to the heavens — the message, the answer, is in our hearts. We do not need to say: 'Who among us can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?' Nor do we need to say, 'Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?' 'No the thing it very close to us, in our mouths, and in our hearts, to observe it.' (Deuteronomy chapter 30 verses 11–14)

As religious believers and as committed Australians, we take a justifiable pride in our national identity and we have the confidence that our relationship with God can shape for the better our contribution to our community, to our professions and our workplaces. But we are called to be prophetic and a little challenging to each other and to our fellow citizens.

Australia is a great place to live but there are still people who miss out, those who fall through the cracks, those who do not get a fair go. I was privileged to chair the National Human Rights Consultation for the Commonwealth Government for the Rudd Government in 2009. My committee found that 2/3 of us think that human rights are adequately protected in Australia. However, more than 70 per cent of us think that those suffering mental illness, the aged, and those living with a disability need better protection of their human rights. There is plenty of work for us still to do, empowering those on the margins, thereby transforming our world.

Some of you will recall that I gave the public address at the Catholic education conference in the bicentenary year 1988. I focussed on the challenge posited by John Paul II's great encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis which emphasises interdependence and solidarity. I had the temerity to suggest that the enrolment rate of indigenous students in Catholic schools at that time reflected poorly on our preferential option for the poor. My remarks occasioned quite some consternation at the time. But things have changed and so much for the better. The number and proportion of Indigenous students in Catholic schools has increased significantly for the period from 1985 (0.9 per cent) to 2011 (2.2 per cent). In 2011 there were 16091 indigenous students in Catholic schools. Students with disability in Catholic schools have increased from 1985 to 2011 (from 0.2 per cent in 1985 to 4.0 per cent in 2011). In 2011, there were 28,730 students with disability in Catholic schools. Since 1988, we have all been privileged to witness the birth and growth of Australian Catholic University, now the Catholic university with the largest student numbers in the English speaking world. Many of our graduates will be teachers in Catholic schools being able to demonstrate a preferential option for the poor through their enrolment policies. They will be agents for transformation and empowerment through the formation of their students.

One of the nation's most experienced Catholic educators, now Bishop O'Kelly SJ, told the 2011 AHISA Conference:

Over time there developed four adages which for me crystallised what I was attempting to do as the head of a Church or values-based independent school. You will note that these adages are all about vision and formation, all helps to knowing thyself and helping people to be true to their own selves.

The first was: we are born to praise, reverence and serve. The second is: the artist is always painting himself. The third is: the heart of education is the education of the heart. The fourth: no school can rise above its common room.

Professor Michael Gaffney, the Chair of Education Leadership here at ACU has written:

Leading Catholic schooling is a strategic, practical and deeply spiritual act. For leaders in Catholic education, this means ongoing reflection and action to ensure that Catholic schools are well positioned:

- educationally — on the edge of mainstream trends in policy and practice, so that they can make a distinctive and valuable contribution to debates and developments rather than be swept along or consumed by those trends;

- socially and economically — on the poorer and the wealthier edges of town (as well as everywhere in between) so that everyone has a fair go, and can support and be supported by others for the common good, i.e. the social conditions that allow people to reach their fulfilment more fully and more easily (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2004), and

- spiritually — recognising and respecting students, staff and school communities 'on the edge of faith' and helping them in their search for meaning and a fuller appreciation of the Word of God, Catholicism and the Church.

This vision of schools is much broader and deeper than the vision reflected in the recently tabled Australian Education Bill which makes four references to 'excellent education'. The National Catholic Education Commission has told the government: 'The word 'excellent' is so overused, so dependent on subjective interpretation, as to be meaningless. The NCEC presumes that here it denotes a 'superior' education, an education that is measurably better in outcomes than current Australian education.' The NCEC has said that a superior education:

- reflects and enacts the aspirations of the parents (including the internationally-recognised right for an education based on religious values);

- recognises and enhances the physical, social, intellectual, spiritual, moral, emotional and aesthetic capacities of each young person;

- helps each young person achieve a productive and integrated sense of his or her personal purpose in life;

- contributes to the nation's social cohesion and economic prosperity; and

- results in optimal levels of literacy, numeracy and social and employability skills for all students.

But what now of the challenge to the university to be an agent of transformation and empowerment in forming teachers for the future like Greg O'Kelly?

Drew Gilpin Faust, the President of Harvard University spoke on scholarship and the role of universities when she was welcomed at Boston College on 12 October 2012. Coming from the premier university of the United States and speaking at a leading Jesuit university, she said:

But we must not let the clarity and measurability of the economic case for higher education lead us to abandon the more difficult work of explaining — and embracing — higher education's broader purposes. By focusing on education exclusively as an engine of material prosperity, we risk distorting and even undermining all a university should and must be. We cannot let our need to make a living overwhelm our aspiration to lead a life worth living. We must not lose sight of what President Kennedy, speaking at the Boston College centennial, referred to as 'the work of the university ... the habit of open concern for truth in all its forms.'

At their best, universities maintain a creative tension, tackling the purposeful and the apparently pointless with equal delight — from the eating habits of the vampire squid to the nature of empire to the technology for optimal vaccine delivery. We must continue to nurture that creative tension. We must value it and encourage it, and assure its place in the structures and modes of academic inquiry and in our understanding of the university's fundamental purposes. Because sometimes the best path to short-term goals is through the unplanned byways of the long-term perspective. We need both. We must remember that in this age of 'outcomes' and measured 'impact' that the means and processes of learning and of intellectual exploration have importance in themselves.

The American comedian (and graduate of the Jesuit University, Boston College) Amy Poehler spoke to Harvard's graduating class of 2011 in a Commencement speech. She told them, 'You are all here because you are smart and brave. If you would just add kindness and the ability to change a tyre, you would be almost the perfect person.' Transformation and empowerment will come through the exercise of kindness and tenderness, accompanied by the practical abilities inculcated by all that a rounded Catholic education has to offer.

Let me offer a blessing to conclude. In 1985, I was walking along the beach at Mapoon on the west coast of Cape York in far north Queensland and saw the largest mango tree I had ever seen. Mapoon had been established as a Presbyterian Aboriginal mission in the nineteenth century. Under the tree I saw Jean Jimmy who had just become a great great grandmother. As ever she was rolling a cigarette. I admired the tree and asked if the missionaries had planted it. 'No', she replied, 'I planted this tree. I am very blessed to sit under the shade of this tree and to see it bearing fruit.' We are blessed to sit under the tree of learning. We are even more blessed to be sent as builders of a peaceful and hope-filled Australia, educators committed to transformation and empowerment for all.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law, director of strategic research projects (social justice and ethics), Australian Catholic University, adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law, director of strategic research projects (social justice and ethics), Australian Catholic University, adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.