2018 Castan Centre Human Rights Conference, Federation Square, Melbourne, 20 July 2018. Listen

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) peoples of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present.

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) peoples of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present.

Thanks for the introduction Professor Sarah Joseph (Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law).

I am delighted to have the opportunity to join such esteemed speakers and to address what for some in Australia is an esoteric topic: Religion and Human Rights. For many years, human rights advocates have acknowledged that Australia's legal architecture for the protection of human rights is patchy and inadequate. During the 2017 voluntary survey on same sex marriage, there was much discussion and agitation about freedom of religion. The Turnbull government set up an expert panel 'to examine whether Australian law adequately protects the human right to freedom of religion'. A member of that panel, I accepted your invitation some months ago to address the outstanding issues which await resolution in Australia when it comes to religion and human rights. Back then, I and the conference organisers assumed that the government would by now have released the recommendations of the Ruddock panel. We were wrong, and thus I am somewhat circumscribed in what I can say.

Current headlines would have us believe that protecting an individual's right to freedom of religion comes at the cost of someone else losing their right to non-discrimination. I don't think that is necessarily the case.

The debate surrounding last year's same sex marriage debate was an example where these views were seen to clash. We can all think of examples where people who hold their religious beliefs were upset by activities undertaken by members of the 'yes' campaign. Some religious folk were even upset with me even though I was not campaigning, though I was very happy to indicate how I was voting and to explain publicly why I was voting as I did.

There was plenty of upset and anxiety on both sides of the debate.

An effective pluralistic society committed to the rule of law and the inherent dignity of all citizens demands that we turn our minds to the best way to balance competing rights in a modern, changing society.

Rather than viewing these two essential rights of faith and non-discrimination as competing against each other, is there a way to have them complement each other thereby strengthening our society?

The international law is quite clear. Freedom of religion is a human right. It is found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Article 18 of the ICCPR states:

1. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching.

2. No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.

3. Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

4. The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to have respect for the liberty of parents and, when applicable, legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions.

The freedom of conscience and religion is one of the few non-derogable rights in the Covenant.

This means that a signatory may not interfere with the exercise of the right even during a national emergency — whereas other rights in the Covenant can be cut back during times of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation — but only to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation and provided that that cut back applies in a non-discriminatory way to all persons.

Furthermore, freedom of religion is one of the few rights which can be confined only if it be necessary "to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others."

Reference to freedom of religion is also found in the Australian Constitution. Section 116 states that the Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.

There have been few cases to consider this section, and none that provides clear advice on its application to non-discrimination matters.

The High Court considered section 116 in The Church of the New Faith v Commissioner for Pay-roll Tax (Vic) in 1983 — the Scientology Case. Justices Mason and Brennan held that 'freedom of religion, the paradigm freedom of conscience, is of the essence of a free society'.

Here in Victoria with your Charter, the Court of Appeal has had cause to comment on the right to freedom of religion in Christian Youth Camps Ltd v Cobaw Community Health Services Limited. Justice Redlich said that freedom of religion is 'a fundamental right because our society tolerates pluralism and diversity and because of the value of religion to a person whose faith is a central tenet of their identity.'

Freedom of religion is not an unlimited right. Chief Justice Latham in Adelaide Company of Jehovah's Witnesses Inc v Commonwealth was careful to point out that not all infringements of religion will be invalidated by section 116, but only those that exert 'undue infringement of religious freedom.'

The US Supreme Court has now offered its view on the freedom of expression of the baker who does not want to bake a cake carrying a particular message. In ruling in favour of the baker Phillips and against the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the Supreme Court found in MASTERPIECE CAKESHOP, LTD. V. COLORADO CIVIL RIGHTS COMMISSION:

'[O]n at least three other occasions the Civil Rights Division considered the refusal of bakers to create cakes with images that conveyed disapproval of same-sex marriage, along with religious text. Each time, the Division found that the baker acted lawfully in refusing service. It made these determinations because, in the words of the Division, the requested cake included 'wording and images [the baker] deemed derogatory,' The treatment of the conscience-based objections at issue in these three cases contrasts with the Commission's treatment of Phillips' objection. The Commission ruled against Phillips in part on the theory that any message the requested wedding cake would carry would be attributed to the customer, not to the baker. Yet the Division did not address this point in any of the other cases with respect to the cakes depicting anti-gay marriage symbolism. Additionally, the Division found no violation of CADA in the other cases in part because each bakery was willing to sell other products, including those depicting Christian themes, to the prospective customers. But the Commission dismissed Phillips' willingness to sell 'birthday cakes, shower cakes, [and] cookies and brownies,' to gay and lesbian customers as irrelevant.'

How would Australian law deal with the baker who doesn't want to make a specially designed cake for a same sex marriage on the basis of religious belief, or with the Jewish baker who does not want to bake a cake with a swastika?

We would all agree that freedom of religion is essential for a healthy pluralist society, even one which is as secular as Australia, and even one where there is an increasing intolerance of religion by the elites. Current discrimination laws in Australia are patchy and not all jurisdictions recognise religious belief as a trait requiring protection.

Under the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act, it is unlawful to discriminate against a person on the basis of a person's sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, marital or relationship status, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and family responsibilities. Note the absence of religious conviction.

It is a deficiency of Commonwealth law that religious belief is not included in the list of protected attributes.

I also note that freedom of religion is not considered a protected attribute in all State based discrimination legislation, NSW and South Australia both being silent on the issue.

In the absence of this specific coverage, and in the absence of a Commonwealth Human Rights Act, where is the right to freedom of religion adequately protected? As Australia is a signatory to the ICCPR, I believe that freedom of religion needs to be more than an exception clause found in various State non-discrimination legislation.

As a member of the Expert Panel that was formed to review religious freedom, chaired by the Hon Philip Ruddock, I can attest to there being no easy answer. The Panel received over 15,000 submissions during its Inquiry period — many of which are available on the Review's website. I would encourage you to look at the vast range of submissions that both support and challenge your personal views.

As part of the Inquiry we heard from people and organisations who are worried about their ability to express their views openly — whether they be supportive of reform or staunch in their support of traditional values.

People were worried that they could lose their job, or be in trouble with the law if they were to publicly state their opposition to a particular change in public policy on the basis of their religious convictions. Others believed that they might lose their job if they were to speak openly about their sexual orientation or religious beliefs at work.

There were many who believed that single issue advocacy groups had grown such in the public domain that their own views, despite being based on considered thought, were no longer legitimate but dismissed without respect as being outdated or wrong.

Others claimed that religious freedom has become a way to legitimise discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex or queer people.

Whilst it is positive that people across the country have had the opportunity to participate in a respectful way in national debate, it is impossible not to be daunted by the range of views expressed.

Let's circle back to the question of how to balance this right with the proper and just application of non-discrimination laws.

In her 2008 book When is Discrimination wrong, Deborah Hellman argues that the core of the harm or wrong is that discrimination demeans or denigrates those against whom it is directed. Demeaning occurs when one differentiates between people in a way that fails to treat them as beings of equal moral worth.

Respect for the dignity of all has to be the core element of any reform and way forward. In my own faith tradition, Pope Francis (and I am a fan as well as a follower) tells the story about being asked about gay marriage and answering that God made us who we are and that God loves all his children equally. I urge all my fellow Catholics, including those who are bakers, to think likewise when engaging with people who have different values and perspectives.

When chairing the National Human Rights Consultation for the Rudd Government, I suggested that the best way to balance these rights in a way that upholds human dignity would be the introduction of a National Human Rights Charter.

It would enable the law to treat people with strong religious convictions in the same way as people who experience discrimination on the basis of current protected attributes.

I voted 'yes' in last year's ABS survey on same sex marriage. As a priest, I was prepared to explain why I was voting 'yes' during the campaign. I voted 'yes', in part because I thought that the outcome was inevitable. But also, I thought that full civil recognition of such relationships was an idea whose time had come. What was needed was an outcome which helped to maintain respect for freedom of religion, the standing of the Churches, and the pastoral care and concern of everyone affected by such relationships, including the increasing number of children being brought up in households headed by same sex couples committed to each other and their children. I thought it appropriate that at least a handful of clergy should come out and, when asked, express their intention to vote 'yes', explaining why a strong 'yes' outcome could arguably contribute to the common good.

Even though most Catholics who voted ended up voting 'yes' as I did, I presume that the majority of our bishops voted 'No'. But I know that some bishops did vote 'Yes'. In the lead up to the vote, a couple of bishops (and there were only a couple, though others may have been upset while deciding not to communicate directly with me) wrote to me taking strong exception to the position I had taken. One of these bishops claimed, 'With regard to the current postal survey on legally redefining marriage to include same sex unions, a Catholic is morally obligated to vote 'no'. There is no option to claim that in good conscience that a Catholic can vote 'yes'.' I disagreed strongly with this bishop. I think I voted 'yes' in good conscience. I thought his argument was the twenty-first century equivalent of a bishop telling the flock that they had to vote for the DLP. I think those days have gone, and they've gone forever.

Archbishop Mark Coleridge, an accomplished scripture scholar and now President of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, got it right when interviewed on national television during the plebiscite campaign. When pressed by David Speers, he said:

'To think of a Catholic vote all going one way is just naïve. Of course, it's possible to vote 'yes'. It depends why you vote 'yes'. It's possible to vote 'no', but equally it depends why you vote 'no' ... As a Catholic you can vote 'yes' or you can vote 'no'. I personally will vote 'no' but for quite particular reasons. But I'm not going to stand here and say: you vote 'no'; and you vote 'yes', and you're a Catholic, you'll go to hell. It's not like that.'

No matter how we voted, we all now need to accept that the civil law of marriage will permit the exclusive, committed relationship of any two persons to be legally recognised, granting the couple endorsement and respect for their relationship and for their family.

How do we move forward with same sex marriage and freedom of religion? Might we look at New Zealand. During the plebiscite last year, Fran Kelly, a strong advocate for the 'yes' vote, told ABC Insiders: 'Some reassurance really for those who are worried about religious protections, religious freedoms, if the 'yes' vote gets up. We had a look at New Zealand — a country, society very like ours. Four years ago, they passed legalised same sex marriage. Basically, no incidents. No concerns of religious freedoms being contested or challenged. The Churches seem to have no issue.'

Earlier, Kelly had interviewed then New Zealand Prime Minister Bill English on ABC RN Breakfast. When asked about same sex marriage, he stressed that freedom of religion is important. She observed: 'You voted 'No' in 2013 but you've said if the vote was held now, you would vote 'yes'. Does that mean that the New Zealand experience of marriage equality has been a positive one for your country?' English replied: 'It's been implemented. There are a number of people taking advantage of it. We haven't had quite the same challenges around free speech and religious freedom as here but I think it's really important that that's maintained. But it's a pretty pragmatic approach really. It's in law. I accept that that is the case: we have same sex marriage in New Zealand and we're not setting out planning to change it.'

When elected prime minister, English described himself as 'an active Catholic and proud of it'. His predecessor Jim Bolger, who had been prime minister in the 1990s, told David Speers on Skynews that there have been no problems with the protection of religious freedom, 'and I say that as a conservative Catholic'. He found much of the Australian debate 'unnecessarily provocative and wrong'. Pointing to Catholic Ireland, he suggested that we should be able to 'put that to history'. He said that New Zealand had been a positive experience and that there were no grounds for victimising people.

I suspect English and Bolger were right. And I have no reason to question their Catholicity. Each of them is a competent, experienced politician well used to weighing the prudential considerations which come to play when contemplating legislation in a pluralistic democratic society.

But there is one point of distinction between Australia and New Zealand which was not considered by Bolger and English. There is a clear legal reason why New Zealand has not had the same controversy around free speech and religious freedom. That's because they already had in place the legal architecture recognising and protecting these rights. For example, the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 provides: 'Every person has the right to manifest that person's religion or belief in worship, observance, practice, or teaching, either individually or in community with others, and either in public or in private.' New Zealand's prohibited grounds of discrimination in their Human Rights Act include 'religious belief, ethical belief, which means the lack of a religious belief, whether in respect of a particular religion or religions or all religions'. We have no such provisions in our Commonwealth laws. And that's the thorny issue. That's the issue that was constantly aired during the plebiscite by the likes of John Howard and Tony Abbott. It will not have escaped this audience's notice that in the past, they and their ideological colleagues have been strong opponents of any statutory bill of rights.

There's no way the Turnbull government will legislate a human rights act. Perhaps they might consider a religious freedom act as advocated recently by Minister Dan Tehan. But even that I doubt. In November 2016, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop asked the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade to conduct an inquiry on freedom of religion. Human Rights Sub-Committee Chair, Kevin Andrews, said the public hearings of the committee would focus on the legal framework of religious freedom in Australia. Prior to the public hearings in June 2017, he said, 'Australia has certain obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and other international human rights instruments. We have an opportunity to examine how effectively Australia is meeting its obligations, with highly qualified legal scholars and religious freedom advocates offering a diverse range of legal opinions. The effectiveness, or otherwise, of these protections, and whether Australia needs a more comprehensive legislative framework, will be discussed in detail.'

One of those qualified legal scholars is Professor George Williams who told the committee: 'Without stronger protection, freedom of religion, along with other basic rights, are vulnerable to abrogation by Parliament. In addition, public debates and policy discussions are not informed by legal structures and standards that ensure freedom of religion and belief is given the status in Australian society that it deserves.'

That Joint Standing Committee issued an interim report in November 2017 with a helpful overview of the current legal framework in Australia. The Senate Select Committee on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill noted in its final report published in February 2017: 'There was common ground between many groups on the need for positive protection for religious freedom. The Human Rights Law Centre and other organisations in support of same sex marriage recognised the need for Australian law to positively protect religious freedom.'

During the conduct of the Ruddock review, the UN Human Rights Committee in Geneva published its concluding observations on its periodic review of Australia's human rights performance. This committee, which has a reputation for a high degree of political correctness in human rights discourse, expressed its concern 'about the lack of direct protection against discrimination on the basis of religion at the federal level'.

Other issues that fall outside the scope of same sex marriage and highlight the need for appropriate protection of freedom of religion include the protection for employees, protection for churches as employers and property holders, protection for churches as educators, and protection for parents and guardians wanting to teach their children according to their religious faith or wanting to spare their children teachings inconsistent with their religious faith.

Under the Fair Work Act, an employer cannot take adverse action against an employee because of their religion or political opinion. Neither can the employer terminate the employee's employment because of the employee's religion or political opinion. Modern awards cannot include terms which discriminate against an employee because of their religion or political opinion.

Should these provisions be extended to protect the expression of religious beliefs as well as membership of a religion and the holding of political opinion? But if you did that, how would you limit the expression of religious beliefs which might be protected? Some expressions of religious beliefs might be so whacky and so insulting to other employees as to make a civilised workplace impossible.

Under the Fair Work Act and the Sex Discrimination Act, religious employers can already discriminate against employees on the basis of their sexual orientation, marital status, religion or political opinion if the action taken is in good faith and is done to avoid injury to the religious susceptibilities of believers, and is done in accordance with the religious doctrines, tenets, beliefs or teachings.

Under the Sex Discrimination Act, religious property owners can discriminate against persons seeking accommodation on the grounds of sexual orientation or marital status when the accommodation is reserved solely for persons of one or more particular marital or relationship statuses. But they cannot discriminate when providing Commonwealth-funded aged care. Once again there may be a case for tweaking this legislation in the wake of same sex marriage. For example would a church boarding school be required to provide married quarters for a boarding master in a same sex marriage?

Under the Sex Discrimination Act, religious educators can discriminate in good faith against teachers and other staff, or even against prospective students, on the ground of their sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status 'in order to avoid injury to the religious susceptibilities of adherents of that religion or creed'. But what if it can be demonstrated that the adherents of the particular religion or creed voted overwhelmingly in support of same sex marriage?

These are all instances of existing legislation which may warrant tweaking in the wake of a strong 'Yes' vote for same sex marriage. But then again, our legislators might judge that the protections are already adequate. The major lacuna in the national architecture for freedom of religion is the lack of any legislative provision allowing persons the freedom to demonstrate their religion, belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching, either individually or as part of a community, in public or in private. A provision of this sort is included in the human rights charters of Victoria and the ACT. The absence of such a provision at the national level helps explain the concern expressed by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Generally the Marriage Act amendments put in place last year do adequately protect freedom of religion in the conduct of marriage ceremonies. There might be a need for some slight tweaking. Other issues of religious freedom could be dealt with by the tweaking of existing legislation such as the Fair Work Act and the Sex Discrimination Act." Our federal politicians will still need to determine how to replicate the Victorian and ACT protection of religious freedom in national legislation.

Public education is also an essential part of the puzzle as freedom of religion has work to do for conservative religious groups with whom many members of this audience might disagree. Dialogue has to be respectful across the breadth of belief.

Governments and religious educators need to work out how best to accommodate all students in their schools including those being brought up by same sex couples and those who identify as L,G,B, or T, and how best to treat all staff including those who enter into a civil same sex marriage. Religious groups are entitled to conduct their institutions consistent with Church teaching but not in a manner which discriminates adversely against those of a different sexual orientation. Religious school providers should treat those of different sexual orientation in the same manner as those of a heterosexual orientation. For example, if an evangelical Christian school were to insist that all heterosexual teachers be celibate or living in a Church endorsed marriage, they would have a case for discriminating against teachers in a same sex relationship. But given that they are more than likely to turn a blind eye (or perhaps even a compassionate and understanding one) to those heterosexual teachers not living in a Church authorised marriage, they should surely do the same for those thought to be living in a same sex relationship.

These and many other matters are sure to be debated strongly once the Turnbull Government releases the recommendations of the Ruddock Review. I thank you for your interest.

Frank Brennan SJ is the CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia.

Frank Brennan SJ is the CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia.

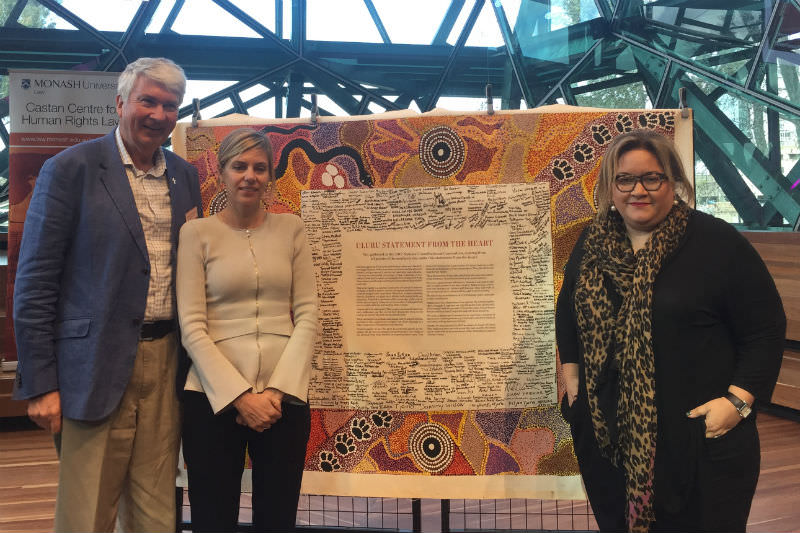

Main image: Frank Brennan with co-panellists Kristen Hilton, Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commissioner, and Megan Davis, Member of the UN Expert Mechanism on Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in front of the Uluru Statement.