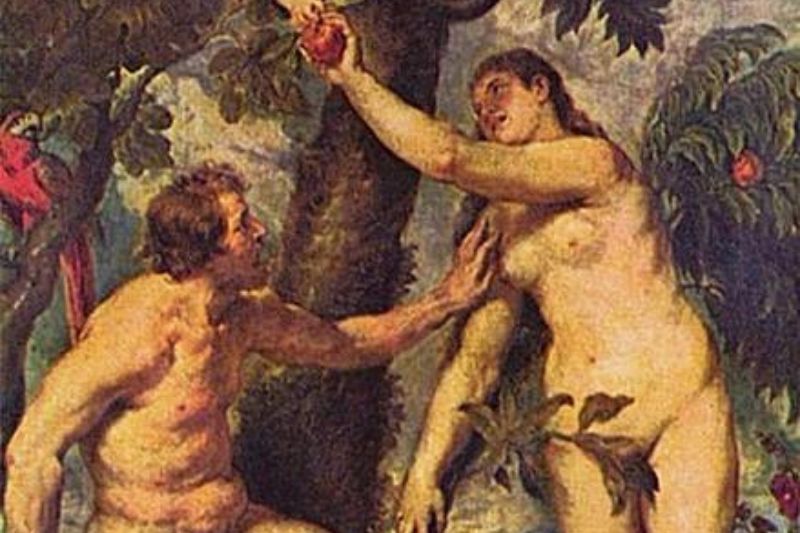

Adam looks spent. He squats abjectly on a rock, gingerly grabbing at Eve’s right boob (for reassurance, or to attempt to stop her?) as she reaches for the shiny apple dangled by a cherub with a serpent’s tail. A dodgy looking fox (ol’ Lucifer?) skulks around Eve’s feet as if to trip her up.

Titian’s The Fall of Man (circa 1550) is one of many works portraying the mythical cosmic gotcha moment; it was informed by similar depictions by Raphael and Albrecht Dürer. (Curiously, all these Adams and Eves proudly display their non-canon belly buttons.) Titian duly inspired Rubens to have a crack in 1628/9; Rubens adds a disconcerted parrot, strips away Adam’s fig leaf and re-casts him as a haggard, middle-aged yob, still clawing feebly away at Eve’s décolletage. (Even Rubens’ poor old fox looks ready for the taxidermist.)

Notwithstanding the weighty theological baggage courtesy of St Augustine etc. (original sin, the inherent depravity of humans post ‘the Fall’), the artworks got me thinking seasonally. To me, the various artistic takes on the ‘tree of the knowledge of good and evil’ look positively autumnal.

Autumn, or the Fall as our North American cousins dub it, is not far off. It’s a time of year that I was largely, blissfully, unaware of as a young Queenslander in sub-tropical Bris Vegas. As I turn 55 this lap around the sun, come wintry June, autumn is conjuring uneasy visions of creeping mortality.

A decade ago the Australian Human Rights Commission reported that the ‘mean age of “old age” for younger Australians is 55.9 years, compared to 66.9 years for older Australians’. Research released late last year suggested almost 30 percent of Australians aged over 50 ‘have been ignored or made to feel invisible… 28 per cent of those in their 50s ‘had been rejected for jobs because of their age, and a quarter of people in their 50s and 60s had been made to feel like they are too old for their work.’

Ye gods, what befalls the not-so-young?

'For those who find themselves firmly in what are declared autumn’s years, there is still much juice to be sucked from life. And winter? Well, perhaps that is not so daunting after all; grey hair often accompanies wisdom and life lessons unrecognised or unheeded by the young.'

Fears of senescence in our physical, social and mental wellbeing. The first throbbing hints of youth’s last gasps. Echoes of possible obsolescence in the work force. The season’s characteristic affinity as the preamble to winter and death is bleakly prevalent throughout much of Western culture.

Robert Browning put it aptly: Autumn wins you best by this, its mute appeal to sympathy for its decay. If Spring is our youth, and Summer the waxing of our strength, then Autumn is the harrowing of us; the cutting down to a ‘less than prime’ scale in the life stages of humanity.

Thomas Hood write ‘The autumn is old; The sere leaves are flying; He hath gathered up gold, And now he is dying… Old age, begin sighing. Strewth. And crikey.

I am of a generation and culture long phobic about aging and dying. We grasp at potency and puissance, influence and concupiscent confluence, through pharmacology and career paths, real estate hordes and investment portfolios. The cascading of leaves off trees heralds our own fears of losses. A future sans hair, teeth, partners, waistlines, income, social networks, relevance, braggadocio, health and happiness.

Autumn has been marked by human rituals to gather in food and fuel to survive winter’s caress. As many of our fellow creatures fly away in pursuit of warmer climes, or grow in their winter coats, we eke out what we can store to stave off hunger and the cold.

The word autumn comes from the old English term haerfest (connected to the Old Saxon hervist, and the old Norse haust, or harvest. I like the Old Irish term for autumn; fogamar, or ‘under-winter’.

We have always reaped what we have sewn, and the proverbial biblical adage, ‘Look to the ant, thou sluggard’ begins to cut uneasily close to the bone in the 50s and 60s.

What have we accomplished? Why have we failed to achieve what looked so easy in our 20s? Who have we helped, what is left to do, why are we not where we thought we would be? Are we soon to experience the ageism and invisibility of generations that have preceded us?

Autumn is a time of laying in enough psychological fodder to stave off the chill doubts that precede our winter. For those of us who are single, or trading precariously in relationships, autumn may set off the melancholic tones of Nat King Cole or Ol’ Blue Eyes himself, Sinatra, crooning ‘I miss you most of all, my darling, when autumn leaves start to fall’.

But even if the plummeting leaves shriek alarums for us, descending Monty Pythonlike toward terra infirma, we do not have to don sackcloth and paint ourselves in the ashes of our aspirations. Faced with the inevitable march of younger and keener generations, the impetus is to share what we gathered. To listen and learn what impact our choices have had on younger voices. To remind ourselves we are still breathing; still warm, still contributing, still sound of limb, wind and mind.

There is a big old world waiting to be explored, whichever hemisphere or atmospheric conditions we find ourselves in. And, as Nathaniel Hawthorne railed, I cannot endure to waste anything so precious as autumnal sunshine by staying in the house.

Autumn is a double-stamped coin; hope offsets fear. In To Autumn (1819), Keats declared the season to be replete with ‘mists and mellow fruitfulness, Close bosom-friend of the of the maturing sun; Conspiring with him how to load and bless’ us. Autumn ripens our fruit, swells our gourds, plumps up our hazel shells and pumps out flowers for the bees until ‘they think warm days will never cease’.

For those who find themselves firmly in what are declared autumn’s years, there is still much juice to be sucked from life. And winter? Well, perhaps that is not so daunting after all; grey hair often accompanies wisdom and life lessons unrecognised or unheeded by the young.

Some researchers suggest that ‘life satisfaction peaks again’ at the age of 69, as with vocabulary, and that ‘men and women feel best about their bodies after 70’ while ‘psychological well-being peaks at about 82’. For those Gen Xers and cohorts eyeing off sports cars, avoiding scales or renewing gym memberships, the season does not mean a summary executing of viability, a vetoing of joy or cancelling of opportunity. F. Scott Fitzgerald suggested that life ‘starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall’. I can fall in behind that adage.

Barry Gittins is a Melbourne writer.

Main image: The Fall of Man (Rubens / WikiCommons)