The first thing I did after reading about the new, bowdlerised editions of Roald Dahl’s books was to buy a second-hand pre-2020 box set on eBay. Why? He is not my favourite children’s author; his narratives are often full of mean-spirited asides, revelling in grossness and vicious humiliation. The stories often lack a reliable moral compass, with revenge frequently the theme.

And yet, I’ve read most of them because they’re still fascinating and grip the reader to care about the flawed protagonists. Willy Wonka is like the Old Testament God in Job: you know, that nice deity who makes a bet with Satan to see how much they can torture the poor old bugger and his family till he cracks and calls God a bastard. Willy Wonka’s capricious cruelty makes you think quite a lot and if you’re lucky, your kid will ask you questions that will lead to other important questions. Because, like his creator, Willy Wonka is not nice.

Lots of creators are not nice people and yet they can create wonder, beauty, compassion, horror, terror. Wagner and Picasso were not good people to know. Shakespeare may well have been complete sweetheart for all we know about the man who left his widow his second-best bed, but he often wrote nightmares. Try Titus Andronicus if you think Tarantino is shocking.

Roald Dahl was not a nice man and neither were his works, but the people whom Andrew Doyle calls ‘The New Puritans’ have now corrected naughty Mr Dahl, just as naughty Mr Shakespeare was corrected centuries before now by Thomas Bowdler, whose name is forever memorialised as what gets done to art by well-meaning vandals.

In one instance among countless that were deemed unfit, Shakespeare had Iago saying ‘I am one, sir, that comes to tell you, your daughter and the Moor are now making the beast with two backs.’ Bowdler took a deep breath, dashed cold water over his unmentionables and gave us ‘Your daughter and the Moor are now together’.

Quite right too, can’t be having all that rudeness, but let’s take a hard look at whether ‘together’ implies that very same rudeness. ‘Together’, eh? Said with a certain inappropriate emphasis that word is pure filth. Down the slippery slope we go, and don’t you dare read anything into that, either.

'In Victorian times, there was a huge industry in producing children’s books that were all about rewarding good children and punishing bad ones. And it is important to realise that nowadays, with different definitions of "goodness" all the major houses are publishing moralising tracts.'

So what exactly has Puffin done to the Dahl books? If you go to the UK Telegraph website (the subscription is very affordable and you may even be allowed a free article) you will find a carefully researched, searchable account of all the changes that have been made to the books. Some examples from Matilda:

‘Mothers and fathers’ have now become ‘parents’.

‘A lovely pale oval madonna face’ – ‘madonna’ has been excised.

‘The plain plump person with the smug suet-pudding face’ – ‘plump’ has been excised.

‘I don’t give a tinker’s toot’ – ‘tinker’s toot’ has been changed to ‘flip’.

‘His mother’ is now ‘His parents’.

‘His mother thought it was beautiful’ is now ‘He thought it was beautiful’.

There are hundreds of other changes. Some phrases and even whole sentences have been completely removed, such as ‘Their children turned out to be delinquents and drop-outs’ and even the richly allusive ‘Bingo afternoons left her so exhausted both physically and emotionally that she never had enough energy to cook an evening meal’.

Other words and phrases removed from Matilda are ones that refer to what sex a person is – ‘boys and girls’ are now just ‘children’. Or the excised material might contain some of Dahl’s signature venom, those vivid sprays of anger and playful spite that are a major reason why his books are so popular. You sort of understand why these sensitivity censors would shudder at the phrase ‘knock her flat’, but not why they would think ‘give her a right talking to’ is in any way an acceptable substitute.

But the true impoverishment of this kind of imagination comes frighteningly clear when you see this next example from Matilda, which I find more awful than any of the others. The original line is an extremely Dahlian bit of prose, rich with allusion and effortlessly informed, passing on the privilege of his cultural background to every kid who read him. This sentence, so surprising to be found in a kid’s book, was cool, dismissive, devastating and redolent with the best of our culture with its nod to Keats’ ‘Endymion’:

Her face, I’m afraid, was neither a thing of beauty nor a joy forever.

A casual, effortlessly valuable aside tossed to your kids, this shining little crumb from a culturally rich man’s gleaming table of goodies. A little treasure that they’ll appreciate more when (or if, sadly in today’s English curriculum) they come across it later. Like tossing them a trinket made by Fabergé, with the added benefit of not being breakable or losable. Unless, of course Puffin’s Puritans get at it.

So, what did our children’s sensitivity guardians do with the little bit of Dahl/Keats? Here you go, kids: ‘Her face was not a thing of beauty’. Boom Tish – two writers cancelled for the price of one.

Defacement of art is something that persists through history as long as human hatred has endured. The Puritan zealot William Dowsing destroyed most of the stained-glass windows in the east of England, stopped only when one of the stipulations in the articles of surrender to Cromwell’s forces decreed that no more places of worship were to be defaced. Under Cromwell, celebrating Christmas was then outlawed, there was to be no more dancing, no more theatre. Purity in the Puritan’s lexicon meant total control of art, imagination and belief by the narrow elders of piety.

In Victorian times, there was a huge industry in producing children’s books that were all about rewarding good children and punishing bad ones. And it is important to realise that nowadays, with different definitions of ‘goodness’ all the major houses are publishing moralising tracts. Stonewall has an awards system for young people’s books that honours the children’s imprints of Penguin, HarperCollins, and many others. Each of the books, if you look them up on the Stonewall Awards site, feature young people, sometimes very young people, navigating the world of LGB and all the letters following.

Being able to recognise oneself in a fictional work may be no bad thing, but that is surely not fiction’s only definition or its full task. And there is another reason for children’s books: they are meant to delight, fascinate, ignite curiosity and even disturb. If a child gets used only to seeing bland and worthy depictions of themselves and their own kind, then they will need something more to give them a sense of what the world is like, and what the other people in the world experience, people who are different from them.

'Defacement of art is something that persists through history as long as human hatred has endured.'

Diversity and inclusion policies at all the publishing houses mandate favourable representation of the categories of people who are seen as marginalised or under-represented. Children, they say, should be able to identify with the main characters. But how does this explain how millions of girls identified with the Harry Potter books? Not just Hermione – the hero himself. And although the Potter books were full of moral challenges and the struggle against tyranny, the real delight was in the fathomless complexity of the detail, the nuances of the moral challenges, the untidy people whom J.K. Rowling imagined into life. Lovable old Dumbledore was a seriously flawed character, while the book’s bravest person, Severus Snape, was also a mean and spiteful bully. Harry himself was often closed and obstinate and had trouble controlling his anger. Even Draco Malfoy is a pitiable character in the end. Her people are not cardboard agit-prop, they have depth and life.

Unlike Roald Dahl, Rowling is well known to be a kind person of demonstrated compassion: her charity, Lumos, has saved thousands of abandoned children from institutions. But that is not the reason to read her books. Roald Dahl didn’t do anything like that, but that is not a reason to avoid or mutilate his books. Because moral turpitude, or spiritual evil, is the most human thing.

Non-human animals, even when killing their own kind, are driven only by drives and instincts, not spiritual evil: they do not murder: we do. It takes a human mind and soul to turn those drives and instincts into lust, greed and wrath. Animals do not ostracise and humiliate their own kind for pleasure, they do it to preserve their group hierarchies, those mechanisms which have preserved them throughout evolution to now. It’s the difference between their edenic innocence and our own damned paradise lost.

If we deny this, if we cease from genuine exploration, using our hearts and souls to guide our lizard drives and intelligent tools, then we lose depth and complexity and become more like robots. And therein lies part of the reason why AI poetry is so bad; shallowness and banality are the clue in this labyrinth.

Being an artist is about being an artist, not a saint. Some of our greatest artists were horrible people: Wagner was such a virulent anti-Semite that his works were able to be appropriated by the Nazis and were used to glorify their demented visions of racial ‘purity’. Picasso was a heartless womaniser and uncaring father. Kingsley Amis and Charles Dickens were horrible to their faithful wives. Eric Gill, a third order lay Dominican, inventor of the Gill Sans font and whose sculptures are everywhere, including Westminster Abbey and the BBC’s main headquarters, lived a life of such extreme sexual depravity that he rivalled the Borgia popes.

Yet no-one is suggesting he be cancelled or that his sculptures be toppled or that Picasso’s nudes have knickers painted over them. And Wagner’s music was rehabilitated, in Israel, by none other than that most wondrously Jewish of great musicians, Daniel Barenboim. If Barenboim could see past the crazed hatred in Wagner’s personal life and celebrate his great art, then perhaps the rest of us could behold art as art and ask right and useful questions instead of Bowdlerising it.

[NB: Penguin has reacted to the backlash (even the Queen Consort weighed in) and is now going to release the unedited texts as 'Classic Roald Dahl' in the adult books while keeping the bowdlerised ones in Puffin.]

Juliette Hughes is a freelance writer.

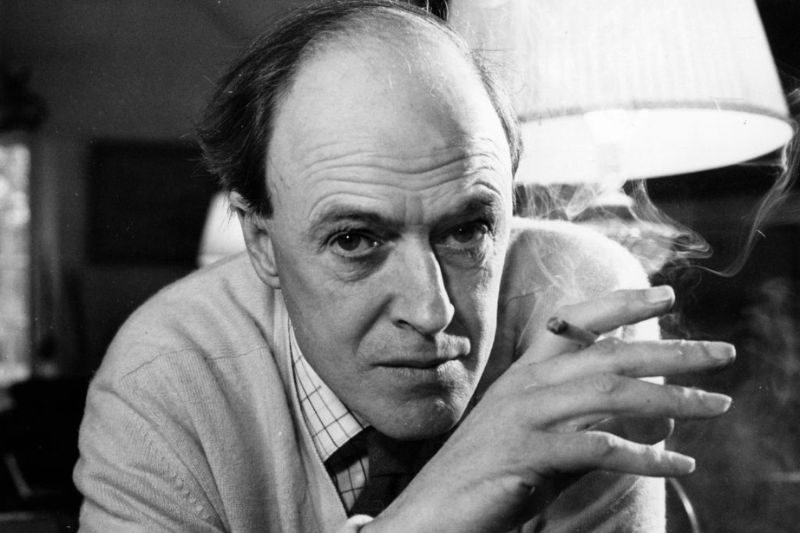

Main image: British children's author, short-story writer, playwright and versifier Roald Dahl (1916 - 1995), 11th December 1971. (Ronald Dumont/Daily Express/Getty Images)