“Nothing is easier than to denounce the evil-doer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”

– Fyodor Dostoyevsky

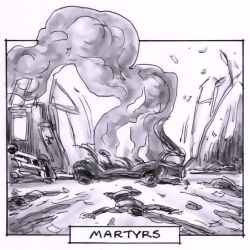

An Islamic martyr (shahid) is a Muslim who died fi sabil Allah (in the cause of Allah). For Muslims to die in the service of and for Allah is the highest form of martyrdom. Martyrs are imbued with special status and reverence among Muslims. Islamic martyrdom has different Islamic constructs and justifications for the diverse versions or interpretations within Islam. Islamic elites have (re)constructed the martyrdom in response to their political ambitions and the prevalent situational factors and environment. This essay will examine three main types of Islamic martyrdom: battlefield martyrdom, non-violent (spiritual) martyrdom and contemporary martyrdom operations. Most emphasis will be placed on martyrdom operations since it is the most contentious. Radical Islamists believe that Islam sanctions the use of martyrdom operations (e.g., suicide terrorism or suicide bombings) under certain circumstances. While these claims are spurious, an important question is why these radical messages resonate with some Muslim communities, such as the Palestinians, living under certain situational factors.

An Islamic martyr (shahid) is a Muslim who died fi sabil Allah (in the cause of Allah). For Muslims to die in the service of and for Allah is the highest form of martyrdom. Martyrs are imbued with special status and reverence among Muslims. Islamic martyrdom has different Islamic constructs and justifications for the diverse versions or interpretations within Islam. Islamic elites have (re)constructed the martyrdom in response to their political ambitions and the prevalent situational factors and environment. This essay will examine three main types of Islamic martyrdom: battlefield martyrdom, non-violent (spiritual) martyrdom and contemporary martyrdom operations. Most emphasis will be placed on martyrdom operations since it is the most contentious. Radical Islamists believe that Islam sanctions the use of martyrdom operations (e.g., suicide terrorism or suicide bombings) under certain circumstances. While these claims are spurious, an important question is why these radical messages resonate with some Muslim communities, such as the Palestinians, living under certain situational factors.

The Quran sanctioned the use of violence against enemy combatants, oppression and injustice. It is beyond the scope of this essay to examine the Islamic doctrine of war and peace, suffice to say that the use of violence is strictly sanctioned by Islamic jurisprudence.

Martyrs (shahid) are revered and rewarded in the physical world and in the afterlife. K. Lewinstein’s book chapter “The Revaluation of Martyrdom in Early Islam” outlines nine benefits enjoyed by the martyr:

“remission of sins at the moment his blood is shed; the privilege of immediately beholding his place in Paradise (there is no waiting until the Day of Judgement); avoidance of the punishment of the tomb; marriage to seventy houris; protection from the Great Terror; the wearing of the Crown Dignity;...and the right to intercede with God for seventy of his relatives”.

The veracity of these benefits bestowed upon a martyr cannot be proven. Nonetheless, these martyr benefits are promoted by Islamic elites (scholars and activists) through a constructed culture of martyrdom, whereby the martyr gains presence and continuity in the community. The martyr’s deeds are ritualised in performances and processions that recall and re-enact the struggle for the cause of Allah. Islamic martyrdom, as outlined below, has been bestowed for diverse acts of martyrdom and importantly, for Islamic elites’ advocacy of diverse political and religious “causes of Allah”.

In the Quran, shahid refers to ‘witness’ and not ‘martyr’. K. Lewinstein contends that early Islamic scholars had likely broadened the meaning of shahid to martyrdom, not because of Islamic jurisprudence or belief, rather the Christian connection of witnessing and martyrdom reflected in antique Christian linguistic usage. The Arabic Quranic word martyrdom (shahada) came from the Greek word ‘martyr’ and Syriac word ‘sahda’. John Esposito, in his influential book Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam, argues that martyrdom comes from the same origin as “the Muslim profession of faith (shahada) or [to bear] witness” that “There is no God (Allah) but God and Muhammad is the Prophet of God”. The Quran expounds little on what constitutes a martyr, rather it states the rewards of martyrdom in Paradise: “Do not say of those slain in Allah’s way that they are dead; they are living, only you do not perceive” (Q. 2:154). Hence, what constitutes a ‘martyr’ is constructed and contested by Islamic elites.

The category of ‘martyr’ has been widened and (re)constructed by Islamic elites due to the prevalent political environment and situational factors. There are three main types of martyrdom: battlefield martyrdom, non-violent (spiritual) martyrdom and martyrdom operations. The expansion of the types of martyrdom enabled those who struggled for Allah in whatever guise to receive the martyr’s reward. However, despite the expansion of the types of martyrdom, not all Muslims who died in battle are eligible for martyrdom. Only those who fought with the proper intention may qualify for the reward of ‘martyr’. Only Muslims who died fi sabil Allah (in the way of God) are qualified for the title ‘martyr’. Those who fought for physical rewards (booty) or for ostentatious display of bravery or suicide or not fi sabil Allah are ineligible for martyrdom.

Outlined below is a brief history of the changing constructions of Islamic martyrdom. Four periods are selected: Early Islam, classical period, modernist period and contemporary era. The Islamic elites’ construction of martyrdom is contested as it changes according to the situational factors. Hence, while each historical period outlined below may emphasise a particular type of martyrdom, it is usual to observe a combination of martyrdoms advocated and practiced.

First, early, seventh century AD Islamic elites initially emphasised ‘battlefield martyrdom’, whereby, the title of martyr was bestowed upon those who died on the battlefield fighting unbelievers. The contested nature of martyrdom was emphasised by the notorious Kharijites (seceders), an obscure Islamic sect, who fought against unbelievers and Muslims not sharing their Islamic vision. They deliberately sought martyrdom (talab al-shahada) by ‘selling’ themselves in exchange for Paradise (Q 4:74 and 9:112). Kharijites advocated an exclusivist and puritanical vision believing that the profession of faith required righteousness and good deeds. They believed that acts of martyrdom were legitimised by their religious justification that they alone were the true and righteous Muslims.

Second, Islamic elites in the classical period, particularly in the ninth to tenth century AD, advocated ‘non-violent (spiritual) martyrdom’ to be bestowed by the inner sacrifice of the believer who died serving Allah. Non-violent martyrdom was evident in the Prophet Mohammad’s era and was reinvigorated by classical Islamic scholars who appealed to the Hadiths that sanctioned the internal sacrifice of believers. According to Richard Bonney, in his book Jihad: From the Quran to Bin Laden, the Hadiths acknowledged several types of non-violent martyrdom. These include death from plague, drowning, pleurisy, abdominal disease, being burnt to death and dying in childbirth. Islamic elites’ emphasis on non-violent martyrdom was influenced by the reaction against the militancy of early Islam and subsequent sedition and political upheaval. Furthermore, the quietism of classical Islamic scholars can be attributed to the promotion of moderation, peace and stability within the expanded Islamic civilisation.

Third, the modern era, nineteenth to twentieth century, initially saw the continuation of a relatively stable political environment within the Islamic civilisation that shaped the pragmatic quietism of most modernist Islamic elites and their continued emphasis on non-violent martyrdom. However, the stability within the Islamic civilisation did not prevent competing Islamic elites from appealing to battlefield martyrdom to mobilise their supporters to fight against their enemies or for their cause (e.g., anti-colonial struggles and national liberation movements).

The break up of the Islamic civilisation into Western sponsored nation-states led to the (re)construction of martyrdom by Islamic elites. They promoted ‘martyrs’ as those who died defending the state rather than those who died spreading and defending the Islamic civilisation. In this guise, nineteenth and twenty century anti-colonial struggles were viewed by modern Islamic organisations (e.g., Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt) as defending Islam and Muslims against colonialism. In contrast, competing Islamic elites, such as Sir Sayyid Khan, sought to counter the Western oriental view that Islam was a religion of violence spread by battlefield martyrs. These Islamic elites argued that Islam is the legitimate state religion of Islamic or Muslim states and is not used to promote violence. These competing accounts exhibited that martyrdom was used to mobilise the state’s nascent police and military forces to defend the motherland. For example, during the Iran- Iraq war in the 1980’s, Iranian state sponsored martyrdom was used as a propaganda tool to mobilise the armed forces and to defend the homeland. In sum, Islamic elites’ promotion of battlefield martyrdom to defend the homeland has similarities with secular politicians’ appeals to patriotism and nationalism to defend the motherland.

Finally, for the purposes of this short essay, contemporary martyrdom operations are defined as politically motivated violence that is conducted by an organisation which specifically targets innocent civilians and ensures the death of the perpetrator. Martyrdom operations emerged from the post colonial struggles of the twentieth century (e.g., Palestinian Occupied Territories). Radical Islamists criticise the quietism of Islamic moderates, which they believe led to the subjugation of Muslims by a coalition of Western and apostate governments in the Muslim world. Radical Islamic ideologues, such as Sayyid Qutb, have sought to return Islam to the ‘straight path’ by reinterpreting and revitalising Islamic doctrines. In Qutb’s seminal book Milestones, he argued that the path to freedom must be hewn by the sword (jihad bil saif). Furthermore, radical Islamists advocated that martyrdom is an individual duty (fard ‘ayn) incumbent upon all Muslims against oppressors, apostates and infidels. They support their claims by citing the Qur’anic verse, “oppression is worse than killing” (2:217). Radical Islamists have extended the construction of battlefield martyrdom from defending one’s homeland or against oppression to contemporary martyrdom operations which instils upon all Muslims, an individual obligation to fight against oppressors even if these oppressors are innocent civilians. Furthermore, they contend that those who oppress Muslims cannot be ‘innocent civilians’.

Moderate Muslims believe that Islamic doctrine prohibits martyrdom operations on three accounts. First, as A. Palazzi states in the book Countering Suicide Terrorism, Islam clearly prohibits suicide as the Quran states “do not kill yourself, for God is indeed merciful to you” and “do not throw yourself into destruction with your own hands”. Second, Islam prohibits the killing of innocent civilians. Finally, Islam affords protection to people of the book – Jews and Christians.

Radical Islamists believe that these three prohibitions are not applicable to Muslims who live under oppressed conditions (e.g., Palestinians living in the Occupied Territories). They argue that martyrdom is based on the Islamic doctrines of ‘Istishad’ (martyrdom) meaning self-sacrifice in the name of Allah. The radical Islamist perspective is exemplified by the late Sheikh Yassin, the former spiritual leader of Hamas, and Sheikh al-Qaradawi, a scholar of Islamic jurisprudence, both of whom sanctioned ‘martyrdom operations’ as a legitimate form of resistance. Both distinguished between suicide and martyrdom, arguing that the latter is a noble act and sacrifice for the liberation of oppressed Palestinian Muslims, while the former is committed for selfish personal reasons, such as ending one’s own life. The late Dr. al-Rantisi, another former leader of Hamas, argued that if one killed oneself because of the environment, that is suicide, but if one sacrificed one’s soul for Allah in the service of defeating the enemy, then that is martyrdom.

Second, Sheikh al-Qaradawi argued that Israel is a military society because men and women serve and are conscripted into the military. Hence, according to this view the casualties caused by martyr operatives are not innocent Israeli citizens because they live in a militarised society. Therefore, radical Islamists believe that there is no distinction between civilian and military targets. Third, Malka asserts that radical Islamists believe that Jews and Christians are protected under Islam only when they live under Muslim rule. Moreover, radical Islamists believe that because Jews have usurped Muslim land in Historical Palestine (Palestine before the state of Israel), hence they have forfeited any protection afforded in the Quran.

The above three arguments lack Islamic legitimacy because martyrdom operations explicitly target and kill innocent civilians. Furthermore, martyr operatives do not die for or in the service of Allah. Rather, they die for their political cause – for example, the liberation of Palestine. Hence, despite radical Islamists’ claims they do not have the right to explicitly target innocent civilians in the service of their clause. Therefore, radical Islamists’ appeals to an Islamic legitimacy for martyrdom operations are unethical.

This short historical account has elucidated that Islamic elites – moderate and radical – have utilised the construction of martyrdom as an effective mobilisation tool in the service of their political ambitions and causes. However, Islamic elites’ construction of martyrdom has reflected the historical experience of Muslim communities and contemporary situational factors. Hence, the martyrdom construct is not created in a vacuum. For instance, radical Islamists’ legitimisation of contemporary martyrdom operations is based on their radical interpretations of the Quran and their empathy with the plight of oppressed Muslim communities, such as the Palestinians. I have argued that the Quran does not sanction the use of martyrdom operations, and it is unethical for radical Islamists’ to espouse an Islamic justification. Nonetheless, a key question for examination is: Why does this radical interpretation of the Quran resonate with some Muslim communities? Offering some suggestions is beyond the scope of this short essay, although I believe examining the situational factors of these communities may offer a starting point.

Ethics of Understanding

I believe a viable alternative to radical Islamists’ martyrdom construct, and use of political violence, is dialogue and understanding of the Other’s actions. I argue for an ethics of understanding that demonstrates a willingness to engage with the adversary (the Other) and understand the Other’s actions. Importantly, this engagement or dialogue between the parties offers an implicit humanisation of the Other. However, understanding the Other, does not mean each party should accept the Other’s reasons or justifications. Rather, understanding elucidates the importance of the Other’s perspective and working towards a viable solution for both parties.

Religious leaders who appeal to the monotheistic God, Allah or Yahweh for legitimacy should understand that all their followers believe in the same higher being and are members of the same humanity.