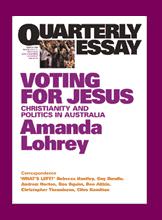

Amanda Lohrey’s new essay, Voting for Jesus: Christianity and Politics in Australia, is the latest manifestation of growing public interest in the way that religion might be influencing the political process in Australia. Its appearance, after Marion Maddox’s widely-read God Under Howard (2005) and before Max Wallace’s much-anticipated The Purple Economy (2007), positions it ideally to snaffle up the attention of all those closet paranoiacs and cynics in the mean time.

Amanda Lohrey’s new essay, Voting for Jesus: Christianity and Politics in Australia, is the latest manifestation of growing public interest in the way that religion might be influencing the political process in Australia. Its appearance, after Marion Maddox’s widely-read God Under Howard (2005) and before Max Wallace’s much-anticipated The Purple Economy (2007), positions it ideally to snaffle up the attention of all those closet paranoiacs and cynics in the mean time.

But this seeming opportunism may prove deceptive. Voting for Jesus contains no new advance on Maddox, and its research is hardly original (indeed, at times it seems little more than a compilation of so much ambient commentary). What then, if anything, is particular to this essay? The answer lies in the way that Lohrey inserts herself into her investigation, those moments when her own spectatorial distance is compromised.

Let’s begin with the scenes that frame Voting for Jesus—those candid discussions with so-called ‘ordinary believers’. Do they not effectively re-stage one of the most clichéd scenarios in cultural anthropology? A benevolent anthropologist comes across some little-known tribal group, isolated from the rest of the world and insulated by its obscure practices. The anthropologist then sets herself the task of ‘understanding’ this tribe. Of course, the story usually ends up with a touching, albeit unlikely, moment when the cultural divide is bridged by a look fof recognition: the initial difference is eclipsed by a realisation of their common humanity. From beneath the primitive rituals—and in contrast to them—shines through something irreducibly dignified, even noble.

But there is something rotten in this ‘cross-cultural’ encounter, a certain two-fold deception at work within it. On the one side, the anthropologist inevitably sees exactly what she wants to see. It’s not just that the attempt to find meaning organises the material in such a way that it becomes meaningful; rather, the very act of ‘understanding’ suppresses an inherent savagery—just one of the words we use to denote the excessive, untransmissible core of any cultural system—in search of the raw nobility hidden beneath the rituals.

In other words, the judgment of what is essential (for instance, the purity of their contact with nature, their age-old, autochthonous wisdom) and what isn’t (sacrifices, brutal patriarchy, etc.) is not only patronising but wilfully self-deceptive. On the side of our anonymous tribe, however, the deception is a little more complicated. Immanuel Kant once suggested that the true historical significance of the French Revolution lay in the way that it transfixed the gaze of those surrounding European nations. In an important sense (even more so now, in our digital-visual era), such revolutionary or even elemental enthusiasm is always ‘performed’ in order to fascinate its benign onlookers.

How does this same scenario work itself out in Lohrey’s essay? Take, for a start, her interview with the three young girls from Hillsong. When asked what ‘God’ means to them, one of girls, Abby, replies:

There’s a God and Jesus is his son. God sees the earth is dying and he’ll give a part of himself in Jesus to save the earth. Jesus is God on earth, God in a form we can cope with.

Upon which Lohrey muses:

God in a form we can cope with? This strikes me as quite a sophisticated thought. And I note the use of the present tense, that the earth is perpetually in a state of dying and the gift of Jesus and his redemption of the earth is a perpetual, ongoing process, not a one-off event that occurred two millennia ago.

The theological sophistication that Lohrey perceives here is entirely of her own making. Young Abby is simply describing God’s motivation for sending Jesus in the first place: "God sees the earth is dying." And it is fully within our parlance to narrate such moments in the present tense. Far more telling is the statement, "Jesus is… God in a form we can cope with," which Lohrey takes up quite nicely later when discussing Jesus’ market value. Such a reduction of Jesus to a mere epistemological supplement, a kind of teaching aid, an explanation of the mysteries of God in a way our puny minds can handle, is a disastrous perversion of the real breakthrough of Christianity.

The earliest Christian theologians—from St Paul to his great intellectual heir, Marcion—recognized implicitly that the ‘meaning’ of Jesus was never so much epistemological (that is, explaining who and how God is) as it was ontological (constituting the most fundamental redefinition of our idea of God to begin with, of what it means for God to be God). Ignoring this aspect, in our time Jesus has been appropriated, commodified, fetishised—that is, made into an ideal personal accessory (a ‘god in my pocket’, much like an iPod or cell-phone) that allows us to function better through the straits of everyday life. And it is precisely this fetishising of Jesus that gives us perhaps the clearest index of the place of religion in political-cultural life today. I’ll have to return to this suggestion a bit later.

Back to my main point. In her eagerness to discover the unexpected intelligence beneath the girls’ remarks, Lohrey misses the obvious: these impressionable girls are just parroting the repetitive sound-bites they are exposed to each Sunday. The clearest indication of this is when they offer inconsistent metaphors for what happens when one indulges in multiple sexual partners (with each new sexual partner you either lose part of yourself, or you take on extra baggage).

These are precisely the sort of equally inconsistent statements they hear from the charismatic but basically illiterate speakers that occupy the Hillsong pulpit. If in this interview, Lohrey was in search of ‘authentic’ belief over and against institutional dogma (as she says she was), here she has found it: these girls really do believe, not in what they are saying, but in the people who said it. And here, I think, we find a specific liturgical economy at work in places like Hillsong, closely analogous to the opaque clerical practices of mediaeval Catholicism: just as ‘canned laughter’ on American sitcoms crack the jokes and do the laughing for you, at Hillsong both the shallow exhortation and the believing response are enacted by the same person. All one must do is believe in the preacher.

At the end of Lohrey’s interview there is a crucial moment, a kind of mise en scène—something that takes place within the interview, that frames the interview itself:

They stand, and Rebecca adjusts her hair in the mirror while Abby leans into my tape recorder and swoons mockingly: "Goodbye. I love you." And the girls laugh and rock out of the room…

The presence of the tape recorder is an internal reflection of Lohrey’s own fascinated gaze. And Abby’s ‘mockingly’ seductive gesture is just that. Even though their belief might be genuine (i.e., not feigned), this doesn’t mean the girls are not performing—as anyone who has disgraced themselves and their sensibilities by watching ‘reality television’ knows, they are simply acting the way they perceive themselves as being perceived. Their self-perception is always already mediated by the recording object; as such, they are, quite simply, playing themselves. Inexplicably, the only person unaware that these girls are performing for Lohrey is Lohrey herself!

Now, my point is not that these girls are more brazen than anyone else; rather, our late-cultural situation has produced new and previously unimagined forms of life—forms that demand anthropologists after their own kind (to which none have come closer than Jean Baudrillard and Slavoj Žižek). It is the very ubiquity of surveillance and digital-visual reproduction that now regulate both the roles we occupy and the activities we perform. So, in the end, there is nothing more profound about these teenage cameos than there is in the inane chatter of the inmates on Big Brother—nor, for that matter, is there anything more admirable or worthwhile about Lohrey’s sympathetic examination, than in that ridiculous early attempt by Channel 10 to present Big Brother as a ‘study in human behaviour’ and subject the inmates’ antics to analysis at the hands of a behavioural psychologist.

Lohrey’s experience with the unnamed female EU devotee is more overtly transferential, and provides us with another, telling moment:

I look at this girl, and she looks back at me, and for the first time there is a painful recognition between us, a recognition that has nothing to do with dogma. There is a mystery at the heart of our being-in-the-world and sometimes we experience that mystery directly and affectingly… But while I respect the experience, I cannot accept the dogma and cultural baggage that has come with it…

In this epiphany—Lohrey portrays it as a kind of pure, wordless encounter, after the woman’s voice ‘trails away’—we have perhaps the clearest instance of self-deception. She sees in the eyes of this other woman precisely what she places there: herself, her own mystical longing in inverted form. The sense of identification is therefore a false one, because it is predicated on the stripping away of words, dogma, the very excess (what Lohrey patronisingly calls ‘cultural baggage’) that constitutes human experience. This, it seems to me, is not only the ugly face of sympathetic identification, but also the very logic of liberal democracy: all religions and cultural forms are permitted to exist side-by-side, provided they are emptied of their excessive element—rather like the reduction of authentic so-called ‘ethnic’ cuisine to the tasteless wares of a Westfield food-court.

An important analogy can be drawn here with John Updike’s latest novel, Terrorist (2006). What Updike claims to offer the reader is the experience of being ‘inside the skin’ of Ahmad, the would-be teenage terrorist, so that one can fully sympathise with him and understand his beliefs: as he told The New York Times in May of this year, "They can’t ask for a more sympathetic and, in a way, more loving portrait of a terrorist." But the result is a character that, at best, is a vulgar stereotype of a disaffected Western Muslim; at worst, Ahmad is little more than a Qur’an-powered automaton. When compared to his remarkable proficiency in the theological idiom and the characterological depth of Roger Lambert—who is surely a version of Updike himself—in Roger’s Version (1986), the sheer paucity of Terrorist becomes even more apparent. And already one can sense here an implicit, patronising judgment: Roger, a Christian theologian, is fluent, adept, resilient; whereas Ahmad, a young Muslim, is woodenly literal, colourless, uninteresting.

In the end, it is not what Updike is actually doing (creating a fairly tedious character) but what he believes he is doing ("reaching for people outside of oneself") that is problematic. James Wood grasped just this point in his wonderful, devastating review of Terrorist in The New Republic: "Whenever Ahmad opens his mouth he sounds like a septuagenarian Indian aristocrat. In fact, he sounds a bit like V.S. Naipaul… but when Ahmad thinks, he sounds like John Updike." It is Updike’s own belief, that he is rendering a sympathetic portrait of a young Muslim, that damns his efforts.

Again, James Wood: "Despite all the Koranic homework, there is a sense that what is alien in Islam to a Westerner, remains alien to John Updike." To take this one step further, it must be said that the only authentic Western fictional treatment of Islam is Michel Houellebecq’s Plateforme (2001), because it contains an essential element altogether absent from Updike’s story: disgust. And it is along these lines that we should read his now infamous remarks to the French magazine Lire in September 2001: "And the stupidest religion is, without doubt, Islam. When one reads the Qur’an, one feels shocked… shocked!" Here Houellebecq paradoxically shows Islam greater respect by acknowledging the foreign element at its core, its constitutive excess that prevents it from being translated into any Western liberal idiom. He thereby avoids the meaningless, condescending reduction of Islam to ‘a religion of peace’, or to a religion that has promoted Western values avant la lettre—thereby all too readily capitulating to our cultural demands.

Let me conclude by returning one last time to Lohrey herself, to her own interest in religious experience. As a self-professed soixante-huitard (1968er), Lohrey is clearly opposed to dogma, the institutionalisation of religion and codification of religious belief. Fair enough. She nevertheless wishes to remain vaguely religious and explicitly adheres to a more indeterminate, "charismatic" (in Max Weber’s precise sense) spirituality.

There is a mystery at the heart of our being-in-the-world and sometimes we experience that mystery directly and affectingly… I don’t believe in coincidences, having observed too many of a profound nature, and in any case I am not an atheist and I do believe that the spirit moves in us… I look at these young adults and they truly are wonderfully made, and I wish we could agree on more; could meet up on some other, wordless, plane, free of dogma, free of all this stuff.

The real question is why does such a vague conception of private spirituality—religion without this excessive element, ‘stuff’—so perfectly suit liberal democracy? The answer that, insofar as liberal or secular democracy has guaranteed space for all religions, these same religions need to learn tolerance and respect for one another in order to conform to our civic code, is only partial. Karl Marx’s solution is far more elegant, and more timely than ever.

For Marx, no sooner had the full impact of the introduction of commerce on the older cultures of Asia Minor been felt—with the result being the ‘desacralisation’ of their experience of the world, the stripping away of those religious palliatives that comprised the mystical dimensions of everyday life—than another religious form came along and took its place. This second religious form, which he called ‘commodity fetishism’, is a kind of illusory depth spontaneously generated by capitalism itself. The effect of commodity fetishism (the inherent belief that things have a mystical dimension that can greatly enrich life and our lived experience) was to soften the subjective blow, allowing us to participate happily within a harsh economic reality.

Thus, according to Marx, crude economics and this illusory religious dimension necessarily accompany one another. A surprising example of this is Sam Harris’ bestselling The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason (2004). After rehearsing the rational grounds on which we should get rid religion altogether (faith has fuelled ethnic and fundamentalist violence for centuries; it is the last vestige of barbarism in our otherwise enlightened sensibilities, etc.), he makes a plea in the final chapter for the importance of Buddhist meditation as a counterbalance to his earlier hardcore cognitivism.

I must confess to growing bored very quickly when I hear that our real problem today is the erosion of spirituality, of belief in a deeper dimension to life, and the consequent rampant materialism. From a properly Christian perspective, the problem today is not materialism, but religion itself. It’s not that nobody believes anymore; it is, rather, that people believe in too much—all those damp, obscure spiritualities that so necessarily accompany our economic situation and, in turn, sustain it. (Authentic materialism, believe it or not, would constitute something like real progress!)

The truth of our condition is that happiness requires an illusion, a fetish, an inherent religious supplement in order to assuage the guilt of our economic debauchery. This fetish could be in the form of any number of activities: Buddhist meditation or supporting a child financially through World Vision; making a donation to Greenpeace or attending mass; watching The Passion of the Christ or listening to a Hillsong CD on your way to work. But here Marx is relentless: in order to change the coordinates of our economic-cultural situation, we must first rid ourselves of the illusion that sustains it: "The demand to give up the illusions about their condition is a demand to give up a condition that requires illusion."