Is there a spirit of place, a kind of psychological imprint that endows a particular location ever after with a discernible atmosphere or mood? There are spots along the Coorong in South Australia where, as twilight deepens, you could swear that wraith-like, dark figures are moving through the dunes softly stirring the empty cockle shells and long since abandoned camp fire charcoal of the middens.

Is there a spirit of place, a kind of psychological imprint that endows a particular location ever after with a discernible atmosphere or mood? There are spots along the Coorong in South Australia where, as twilight deepens, you could swear that wraith-like, dark figures are moving through the dunes softly stirring the empty cockle shells and long since abandoned camp fire charcoal of the middens.

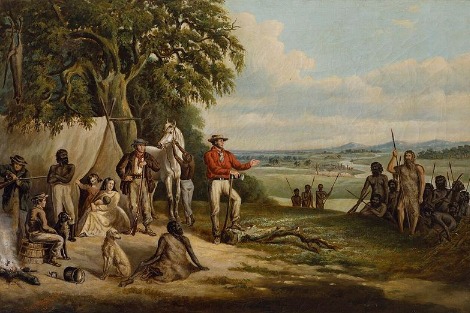

Perhaps the legendary William Buckley lives on in that way on Victoria's Bellarine Peninsula. Buckley, transported for life in April 1803 for receiving stolen goods, escaped in December of that same year and walked round Port Phillip Bay — in contemporary terms, from Sorrento to Point Lonsdale. Welcomed by members of the Wataurong Nation, who may have mistaken him for the reincarnation of their dead chief, he settled down for the next 32 years respected by the Wataurong and soon given up for dead by the authorities.

Buckley learned the language and customs of the tribe and was given a wife in a ceremony on the beach.

There is a version of this story on a plaque near the Point Lonsdale Lighthouse. To those for whom this is part of the daily walk, the view is familiar yet ever changing: dolphins arching through flashes of sun, or the red pilot boat bashing through the swell into Bass Strait, or a cargo ship stacked high with containers, stately in its unruffled glide into the expanses of the bay.

What was unusual in this familiar scene as we neared the Lighthouse along the cliff top a few days ago — a little drama William Buckley may have long ago prefigured in his Wataurong ceremony — was a dazzling white, thoroughly traditional bride with her bow-tied groom, celebrant and a handful of beautifully dressed guests.

They were on the beach near the jetty, cheerfully battling a stiff buffeting southerly. Hats askew or blowing away, the bride's snowy veil flowing horizontally out behind her like a jet stream, and words — possibly formal and seriously binding — lost as soon as uttered, flicked away by the booming wind or drowned in the surging surf.

We headed round to the back beach which, hammered by the gale and with froths of spray curling off the wave crests, was empty. Well, not quite. Down near the water, safely clear of the rhythmic rush and crash of the incoming tide, were a man and a woman. The young man was poised on one knee in front of his companion and looking up into her eyes. She, for her part, was bending slightly forward as she looked down at him. The wind lifted and furrowed her long chestnut hair.

Suddenly the young man stood up, waved and ran towards us.

'Hey,' he called. 'Hey.'

'What's the problem?' I said, rather inanely. After all, he wasn't drowning. He couldn't have just that minute run out of money and decided to cadge a loan. And it didn't look as if he was going to mug us.

'No problem,' he said, and I could see, now he was close up, that he was smiling broadly. 'I just proposed, and she said yes.' As we spoke, his new fiancée was walking jauntily towards us.

'Fair dinkum? You wouldn't be having us on?'

'Of course he's not,' my wife said and, turning to the young man, 'Congratulations, that's wonderful news. We wish you every happiness.' A woman can pick a successfully popped question from 40 paces even in a gale.

As if suddenly noticing that we were complete strangers, the young bloke became embarrassed. 'Just had to tell somebody. We saw a wedding back there on the front beach and it sort of decided me to take the plunge.'

'Like William Buckley,' I said.

He looked blank.

'An escaped convict. Early 19th century. Came down here and lived 30 years with the Aborigines — the Wataurong Nation. Married one of them somewhere along here. This is a marriage beach. You came to the right place.'

They laughed, said goodbye and set off rather awkwardly because walking on sand in a high wind with your arms around each other is tricky. Climbing the steps back to the lighthouse, we met another young couple coming down.

'See those two on the beach,' I said as we drew level. 'They've just this minute got engaged. When you catch up to them, give them a round of applause.'

They looked at me in amazement and laughed. 'We will,' said the young bloke. 'You won't believe this, but we're on our honeymoon. And there's a wedding back there on the beach. Weddings everywhere!'

'It's as if we've all escaped,' his wife said, 'or eloped and come to the same place.'

Was that a knowing sigh I heard back there in the inscrutable dunes — a spirit of this place — or just the dispassionate and immemorial whispering of the coastal spinifex?

Brian Matthews is honorary professor of English at Flinders University and an award winning columnist and biographer.

Brian Matthews is honorary professor of English at Flinders University and an award winning columnist and biographer.