12th Annual Commemoration

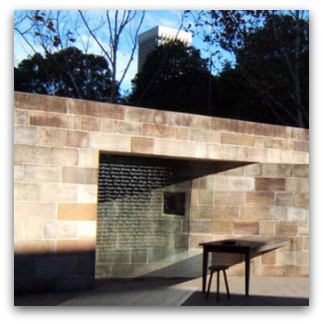

The Irish Famine Monument

Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie Street, Sydney

Sunday, 28 August, 2011 at 12.30pm

I dedicate these remarks to Paddy McDonald, the Irish Australian collector-connector who last month celebrated his biblical birthday of three score years and ten. Paddy has done so much for those new Irish who call Australia home. He phoned this morning to wish us all well here at the Hyde Park Barracks. He was calling from the Charlie Chaplin Festival at Waterville in County Kerry. Being a Brennan and my mother an O’Hara, and being a fifth generation Australian many of whose forbears arrived in the 1860s, twenty years after the famine, I am delighted and honoured to accept this invitation from the Great Irish Famine Commemoration Committee and the Consul General of Ireland to address you on this 12th Annual commemoration here in Sydney.

I dedicate these remarks to Paddy McDonald, the Irish Australian collector-connector who last month celebrated his biblical birthday of three score years and ten. Paddy has done so much for those new Irish who call Australia home. He phoned this morning to wish us all well here at the Hyde Park Barracks. He was calling from the Charlie Chaplin Festival at Waterville in County Kerry. Being a Brennan and my mother an O’Hara, and being a fifth generation Australian many of whose forbears arrived in the 1860s, twenty years after the famine, I am delighted and honoured to accept this invitation from the Great Irish Famine Commemoration Committee and the Consul General of Ireland to address you on this 12th Annual commemoration here in Sydney.

Tom Power has invited me to look forward and around us, rather than back and at Ireland. But of course some of us can’t do one without the other. It’s in our blood and bones.

Twenty-five years ago, I was visiting the Woorabinda Aboriginal Community in central Queensland. Two Irish Sisters of Mercy were living and working in the community there. One evening three charming young Irish backpackers arrived to stay with the sisters. We were all sitting around the kitchen table when one of the local Aboriginal residents became a little testy asking why these three very white, unsunned, young women had come to Woorabinda. One of them smiled, replying, “If you came to Ireland, you would want to meet the Irish. We came to Australia and we wanted to meet you, the Australians.” The inquirer was not only pacified; he was charmed.

A week or so later, I was alone in the church presbytery at Mt Isa in outback Queensland. The phone rang. An Irish lass explained that she and her two companions were backpacking around Australia and they would like to stay the night. I said, “Ah to be sure, you are the three teachers who I met last week at Woorabinda.” No they were not. They were nurses and they had never been to Woorabinda. Around they came, then asking where they might go busking in the morning. Not being an expert on busking in Mt Isa, I told them that I would ask the parishioners after mass in the morning. Being fine Irish lasses, and this being some years before the present troubles with the Catholic Church in Ireland, they said they would come to the parish mass.

I told them they might prefer to come with me later in the day when I would be celebrating a mass with some Aboriginal locals out in the bush. They replied, “To be sure, we’ll come to both.” Ah, those were the days! The parishioners not only told them where to go busking; they then turned up in droves and filled their money cans being enthralled by nothing more that the Irish tin whistle and a few ditties. At the afternoon Eucharist, the buskers then exchanged songs with the Aboriginal celebrants, concluding with the Irish blessing. I wanted to provide a touch of entertainment and sustenance for them before they caught the Greyhound bus to Darwin, and I knew that the Mt Isa Irish Club was the largest such club in regional Australia. I phoned the club to explain my predicament. The attendant informed me that there would be no problem. I could be signed in as an honorary member being a visiting clergyman, and I could then sign in the girls as my guests. All manner of things was well, as they often tend to be when the Irish grace our shores.

At the time of the famine only 2% of those who left Ireland came to Australia. But then in the decade 1851-60, there was a steep increase with the number of Irish emigrants to Australia rocketing from 23,000 to 101,540. Between 1861 and 1870, another 82,900 came to our shores – 10% of the total who left Ireland in those years. Patrick O’Farrell makes the point: “Australia’s vast distance from Ireland, dictating little chance of return, implied two contrasting sets of migrant attitudes, that which looked on it as a great adventure, and that which saw it as a very deliberate and considered decision.”

My O’Hara great great grandparents arrived in South Melbourne in 1864. The previous year the 40-year-old widow Annie Brennan with her five children aged 8 to 20 arrived in Maryborough Queensland on 9 July 1863. Being widowed, Annie (nee Doyle) probably left Ireland being unable to inherit any of the Brennan or Doyle lands around Muckalee in County Kilkenny. She and her children arrived in Australia on the David McIvor which had left Liverpool 106 days before. Only one life was lost on the voyage and nine babies were born en route. 404 new emigrants were on board. The Brennan family paid 90 pounds for their passage. The 28-year-old Martin Geraghty was also on board. He married Annie’s eldest daughter Catherine aged 20 years on 9 May 1864. In 1871 Martin Geraghty and Annie’s eldest son Patrick established the Brennan and Geraghty Store in Maryborough which was run by two generations as a family business for a century. The store is now a National Trust building. Annie’s daughter Julia became the proprietor of the Engineer’s Arms Hotel and the Ariadne Hotel in Maryborough. Another daughter Bridget married publican John Brough. They were at the Forrester’s Arms Hotel in Rockhampton.

Welcoming the David McIvor to Maryborough on 9 July 1863, the Maryborough Chronicle had editorialised: “Maryborough is comparatively but of yesterday, hastily put together and rough, but we can give a homely welcome to strangers, and that is more than many of us have received when we landed a few years since….Immense blocks of land on the banks of the Mary (River) have been surveyed into farms of all sizes, being soil of the richest description for farming purposes….The means are everywhere abundant for material prosperity; it only wants energy, skill and industry, to turn them to good account.”

The year after the arrival of the David McIvor, the Queensland Government Emigration Office amended the regulations relating to land orders for new settlers. The government dropped the restriction requiring men to be under 40 years of age and women under 35. They also opened land orders up to all passengers, and not just those who paid full fare. This decision was made in the face of objection by public servants who warned: “Thousands of persons paying from 5 to 10 pounds each but represented as full paying passengers will be poured into the Colony to increase the power, the influence of their party, the best land will get into their hands, and the true interests of the Colony will suffer in proportion.” Children were eligible for a one half land order. Each eligible passenger was to receive a land order to the value of 30 pounds. Some of the passengers who had come on the David McIvor were assisted migrants who had paid only 8 pounds for their passage, having forfeited any claim to a land order on arrival. This was some generations before the High Court’s Mabo judgment provided us with a better understanding of property rights.

Martin Geraghty grew fruit trees on his 46 acres at Tinana. On 26 January 1864, Henry Jordan from the Queensland Government Emigration Office in London had written a report on the recent Queensland arrivals noting: “It is gratifying to have to report the safe arrival of so many of these persons, who, through no fault of their own, were reduced to a state of absolute starvation…but have now reached one of our own colonies where the demand for labour, and its liberal remuneration, will secure their realising a good livelihood, and where many of them may, by patient, persevering industry, realise a comfortable competency, or even attain wealth.”

On Tuesday I was walking by the Swan River at Fremantle in Western Australia minding my own business, as a Jesuit is wont to do, especially on a sunny winter morning – chatting with a fellow Jesuit and mulling over what I might say today. In the opposite direction walked a chap partly disguised by his cap. He passed me, turned back and with the Irish brogue said, “You’re Fr Brennan aren’t you?” I replied in the affirmative, and without further ado, he told me his life story. He had been a serving boy in the dining room at Maynooth College in 1962. He thought I had been a personal friend and confidante of Archbishop Mannix. I had to confess that I had never met Daniel Mannix, and I had not written his biography. My interlocutor had served some of the greats before migrating to Australia, making his fortune and then losing most of it. We talked about contemporary Ireland. Neither of us had profound new insights. He compared his contemporary countrymen with children who had been let loose in the sweet shop, and now they were paying for it. We moved from the economy and the politicians on to the society and the untrustworthy profligacy of some of the contemporary business leaders, and then of course he asked my opinion on the state of the Church in Ireland. We agreed that the politics, the economics and the religion have all been on hard times. I suggested that politics here was also in the doldrums and that the Church had also known better times.

As we walked on, I and my Jesuit companion ruminated on the strong intervention by the Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny, a practising Catholic, who has accused the Vatican of adopting a “calculated, withering position” on abuse in the wake of a judicial report that accused the Holy See of being “entirely unhelpful” to Irish bishops trying to deal with abuse.

On reflection, I wondered how we had got to the stage that the Irish thought their elected leader had basically got it right in telling the Parliament that the most recent independent judicial investigation into the handling of clergy sexual abuse in the Diocese of Cloyne “exposes an attempt by the Holy See to frustrate an inquiry in a sovereign, democratic republic as little as three years ago” thus excavating “the dysfunction, disconnection, elitism and the narcissism that dominate the culture of the Vatican to this day.” There is presently a profound spiritual famine and disillusionment in Ireland. But the spirit of the people is still strong.

Last year, I was visiting Dublin with a fellow Jesuit from Australia, one Michael Hedley Kelly. On a very cold Saturday afternoon, we paid a visit to Kilmainham Gaol. Our guide was a young fellow in his early twenties, very well educated, well versed in the history of the jail and those who had passed through as prisoners on their way to execution. He recalled all those Irish heroes of 1916 who passed through the cells on their way to execution in the courtyard. We were very moved to stand in front of the makeshift wooden altar where Grace Gifford married Joseph Plunkett in the presence of Father Eugene McCarthy at 11.30pm on the night before Joseph was taken out and executed on 4 May 1916. We heard how at 2am they had been permitted ten minutes in Plunkett’s cell together in the presence of a throng of British soldiers.

At the end of the tour Michael Kelly went up and introduced himself as an Australian Jesuit who had worked in Hong Kong with Fr Joseph Mallin SJ. Joseph is the last surviving child of any of the 1916 rebels. His father, Michael Mallin, a leader in the 1916 rising, called his family to Kilmainham Gaol on the eve of his execution, and prayed that his little son Joseph would be a priest. 94-year-old Joseph is still ministering in Hong Kong. The guide then told Fr Kelly that Fr Mallin had made the same tour of the jail as we had just one year before. Our guide was in fact his guide. Fr Mallin had not identified himself until the end of the tour. He then came forward, introduced himself, thanked the guide, and explained, “I just wanted to come and see where my father was killed. My mother always told me that I was brought here as a baby the night before my father died. My father told my mother not to wake me. She obeyed. I never saw my father again.” Kilmainham Gaol took on a whole new significance for us two visiting Australians.

On Friday, Glenn Stevens, Governor of the Australian Reserve Bank, said, “When I started at the Reserve Bank, the notion that you could have 5-ish per cent unemployment, 2-ish or 3-ish [per cent] inflation, was a dream in those days.” We Australians today are very fortunate that this is our reality. It remains a long distant dream in Ireland with an unemployment rate of over 14%. The Irish faith in major institutions – politics, economics and religion – is at a low ebb, and for the most understandable of reasons. It is not a famine, but it is mighty grim. Not only are thousands of Irish availing themselves of the 457 visa each year here in Australia, there are now more than 18,000 a year coming on the Irish Working Holiday Visa.

Those aged between 18 and 30 can come and on a working holiday for up to a year. If they do 86 days work in remoter parts of Australia, they can then stay an extra year. All up, there are 22,000 young Irish folk here at the moment on these working holiday visas. I was speaking to an Irish lass on Friday who told me that some of her old school friends “who never travel without a hair straightener” were here in Australia on working holiday visas having done crocodile farming in Darwin, fruit picking out west, and snake handling in Queensland. She told me, “If it’s nasty and dirty, they’re doing it.” The latest Irish Echo features a front page photo of an Irish mum’s group set up in Melbourne to support the young émigré mothers. There are many such support groups being established around the country. Sadly there are many Irish who when they come on a 457 visa have to leave their family behind. If not, they are required to pay up to $5,500 per annum for the education of each child in a state school, and they do not qualify for Medicare.

As we remember the famine and ponder the present trials of contemporary Ireland, let’s hope we can offer the same welcome to the new Irish Australians as the Maryborough Chronicle offered the widow Annie Brennan and her five kids five generations ago: “[W]e can give a homely welcome to strangers….The means are everywhere abundant for material prosperity; it only wants energy, skill and industry, to turn them to good account.” And let’s hope the Irish spirit will find again what Seamus Heaney calls Miracle in the poem calling to mind the aftermath of his stroke at Donnegal in 2006:

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in—

Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let up

Until he’s strapped on tight, made tiltable

And raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

For the burn of the paid-out ropes to cool,

Their slight light-headedness and incredulity

To pass, those ones who had known him all along.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at the Public Policy Institute, Australian Catholic University and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at the Public Policy Institute, Australian Catholic University and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.