Chancellor Richard Torbay, Vice Chancellor James Barber, ladies and gentlemen:

Chancellor Richard Torbay, Vice Chancellor James Barber, ladies and gentlemen:

I join you in acknowledging the traditional owners of this place.

I am delighted to have come to Armidale to hear the appellation that I am an ethical blur under the nation's saddle. It was Kevin Rudd who first described me as an ethical burr under the nation's saddle. Clearly this was no Freudian slip by your Vice Chancellor who has known me a long time. With his distinguished academic background in social work and the social sciences, he is not one for idle Freudian slips. I will continue to make much of his introduction of me as an ethical blur under the nation's saddle.

Given the present political paradigm to which I am sure at least one of our honoured guests, the Honourable Tony Windsor, could attest, an ethical blur under the nation's saddle is probably as close as we get in our national life at the moment to moral clarity on some of the issues that we are confronting.

I am very grateful to be with you here today, and I am sure you are all very grateful on such a splendid occasion. It's an invidious task to give such an address today. It is such a beautiful springtime day here on the New England Tableland. I am all that's standing between you and your graduation, between you and your graduation lunch, between you and a long weekend, and perhaps even a Swans victory. So how could one possibly reflect maturely on some of the ethical challenges before us?

My message to you today is simple.

- First, be grateful.

- Second be able to see every situation, every issue, every work situation, and every relationship from both sides.

- Next, develop a true sense of history.

- Next, always imagine how things can be better. This is my challenge to you now as university graduates. What this country, what this region, what this world cries out for is intelligent, educated people who imagine how things can be better.

- Then read and think beyond your profession and beyond your discipline. I as a lawyer can attest that there is nothing more boring than lawyers speaking to each other. Or maybe there is. That is when lawyers speak to the nation legalistically. And who cares? And yet law is absolutely central to the maintenance of our liberty. Law is no substitute for our citizens' commitment to liberty. But it is a worthy buttress. The US judge Learned Hand once said; 'Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it; no constitution, no law, no court, can even do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.'

- As educated persons of the 21st century we must be able to transcend our disciplines and transcend our professions. This is not an injunction to abandon your learning in your discipline, but rather to put it in the context of all human reality.

- Next, you must always be able to distinguish what is right or wrong from what will work or what you can get away with. Ethical and moral quandaries confront us all no matter what our society, no matter what our religious or philosophical background or none. Each of us needs to develop a comprehensive view of the world and a comprehensive set of ideas.

- And finally I would put to you as the modern graduates of this university with its outreach to distance learning that you need to see yourselves as citizens of the world. For many of you, coming to this university has been the first step in this global journey as you hail from nations other than Australia. Those of you who are Australian graduates have had the opportunity to study with some of the best and most able from other countries. The rhetoric of being part of the region and part of the globalised world has taken root here in your lecture rooms and tutorials.

One of the great things about universities, once we get beyond the talk of government education policies and scarce resources, is the capacity to reflect on contemporary events particularly in the light of history.

Might I give you an example. Just take a look at the topics covered by those receiving the Doctor of Philosophy today. I will mention only three. Antero Da Silva has written on 'FRETILIN Popular Education 1973-1978 and its relevance to Timor Leste Today'. How it thrills the heart of someone like me who spent 15 months directing the Jesuit Refugee Service in East Timor after the conflagration that occurred there in 1999-2000. Here as a mature academy, we can foster a consideration of complex questions at doctorate level. Then, perhaps putting party politics to one side, consider Lorraine Taylor-Neumann's 'Demonisation and Integration of 'Boatpeople' in Howard's Australia: A Rural City's Struggle for Human Rights of Asylum Seekers'. Some years ago I wrote a book Tampering with Asylum. On my last visit to Armidale I spoke at the annual fundraising dinner for the Asylum Shelter and Sanctuary program. Mr Windsor can attest, as a nation, we are still wrestling with what will work and what is morally and ethically appropriate when it comes to dealing with asylum seekers. We need people doing considered doctorates to help shape the moral and political consensus of the nation. It is a long road. And finally, Nuttamon Terrakaul's 'An Examination of Community Based Enterprises and Poverty Reduction in Rural Northern Thailand'. I was privileged in 1987 to live for some months on the Thai Cambodian border while working in the Site Two refugee camp. How heartening that here in the peace and serenity of the University of New England such topics can be considered.

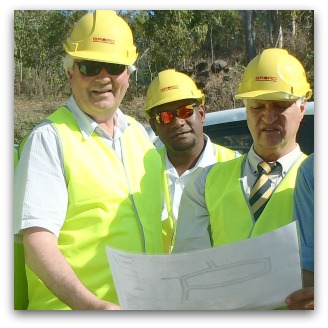

As you take up these challenges, let me reflect with you a little from my past week of travel across this continent. Early in the week, I was on Palm Island, the largest Aboriginal community in Australia, just off the coast of Townsville in North Queensland. I was with one of the more colourful independent members of federal Parliament. Unlike the bare headed Mr Windsor here, this gentleman was wearing a large hat. In fact his hat was even bigger than that of Senator Barnaby Joyce who is wearing the largest hat in the crowd here today. I had the pleasure of enjoying the company of the Honourable Bob Katter who I had first known as the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in Queensland back in the 1980s. We attended a series of meetings with Aboriginal Councillors before then addressing a public meeting on the island.

Some say there has been little development, growth or change on these remote Aboriginal communities. Unlike the situation 30 years ago, we sat down to meet with educated, empowered councillors in control of their local community affairs. They took us to inspect two new subdivisions for the building of more than 70 new community houses. This was unimaginable 30 years ago. It's not that things are now perfect. At our public meeting, Lex Wotton one of the most respected residents of the island was in attendance with his parole officer. He was convicted of rioting after the tragic police watch house death of Cameron Doomadgee in 2004. He is still not permitted to attend a public meeting except in the presence of his parole officer. After an extensive round of police cover-ups, no Queensland police officer has faced any disciplinary action for the death of Doomadgee nor for the cover-ups that ensued. Just last week the retiring police commissioner of Queensland, Bob Atkinson said, 'Palm Island was a tragedy for everyone involved.' It was his one major regret as police commissioner. Mr Wotton is the only one to have had his civil liberties constrained.

There are challenges for us. We look at these challenges in the light of history. Outside the council chamber on Palm Island there is now a memorial to the seven men who led the 1957 strike against the oppressive reserve conditions of the Queensland Government. The inscription reads: 'In June 1957 seven men were arrested at gunpoint by police, during the night. (They) were herded like cattle onto a boat and sent to Townsville....These seven leaders were found guilty of triggering a long planned strike for better wages, food and housing. They also called for the removal of the superintendent. They were deported to other settlements from their home, Palm Island. The media repeated the government's opinion that a riot had been put down. The following inquiry found there had been no damage either to property or persons and the strikers had convincing grievances.'

I like going back 240 years in legal history to the great judgment of Lord Mansfield in Somerset's Case — the case heard in London about the slave who was held there. Lord Mansfield declared in 1774, 'The air of England is too pure for any slave to breathe; let the black go free.' It took generations of campaigning by people like Lord Wilberforce and little people of whom you have never heard — public servants like one Granville Sharp — to agitate for these changes. Ultimately the House of Commons passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

Hal Wootten who was the foundation dean of the University of New South Wales Law School has spoken of what he calls 'the little nudger' view of history. All of you graduating here today wonder what contribution you will make to the world. How will you make a difference? Each of us can be a little nudger. We can nudge things in the right direction — within our profession, within our discipline, in our relationships and within our world. Every now and again, there will be a Lord Mansfield moment. And every now and again there will be a Lord Mansfield. Who knows? There may even be a Lord Mansfield here today amongst the graduation class of Spring 2012. That's the challenge and invitation for the years ahead.

Contemplate our present situation. Forty years ago, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established in front of the old Parliament House in Canberra. We need to see the situation through the eyes of those who protest. Ask yourself, why are they still there after 40 years? What are they seeking in justice? Think to yourself: it is only 20 years ago that Australia had its own Lord Mansfield moment when the High Court of Australia recognised the rights of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders to their traditional lands in the Mabo decision.

There is still much for us to do as a nation ensuring justice for all. Think also of our faltering efforts to act justly when dealing with refugees and asylum seekers, wanting to maintain the security of our borders while acting fairly towards all who seek asylum and not just those who can afford to come here by plane or even by leaky boat. We must distinguish that which is workable and that which is ethical or moral. These are the challenges to you, the new graduates, who take up where the old graduates have left off.

I join with you in thanking the faculty, your families and friends who have supported you so strongly to bring you to this moment. I urge you to be grateful, to always see things from both sides, to develop a sense of history, to imagine how things might be better, to read and think beyond your discipline, to distinguish what is right or wrong from what will work or what you can get away with, and be able always to see yourselves as citizens of the world. If you do this you will be worthy graduates of the University of New England. As such, I salute you. Thank you and Congratulations.

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's University of New England graduation address on 28 September 2012. Photo: Fr Frank Brennan and Bob Katter with Mayor Alf Lacey and councillors of Palm Island inspecting new subdivision.

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's University of New England graduation address on 28 September 2012. Photo: Fr Frank Brennan and Bob Katter with Mayor Alf Lacey and councillors of Palm Island inspecting new subdivision.