I acknowledge the traditional owners of this place and pay my respects to elders past and present, present and absent.

I acknowledge the traditional owners of this place and pay my respects to elders past and present, present and absent.

It is always a great privilege for me as an Australian Catholic priest to be invited the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic Council. This last week I was on Palm Island and in Townsville meeting with some of the Aboriginal Church elders and with Fr Mick Peters who always seems to be the happiest, most contented priest in Australia. Last Sunday he had ten baptisms! His commitment to pastoral ministry amongst your mob is legendary.

It is 30 years since I first visited Palm Island. Some say there has been little development, growth or change on these remote Aboriginal communities. Unlike the situation 30 years ago, we sat down to meet with educated, empowered councillors in control of their local community affairs. They took us to inspect two new subdivisions for the building of more than 70 new community houses. This was unimaginable 30 years ago.

It's not that things are now perfect. At our public meeting, Lex Wotton one of the most respected residents of the island was in attendance with his parole officer. He was convicted of rioting after the tragic police watch house death of Cameron Doomadgee in 2004. He is still not permitted to attend a public meeting except in the presence of his parole officer. After an extensive round of police cover-ups, no Queensland police officer has faced any disciplinary action for the death of Doomadgee nor for the cover-ups that ensued. Just last week the retiring police commissioner of Queensland, Bob Atkinson said, 'Palm Island was a tragedy for everyone involved.' It was his one major regret as police commissioner. Mr Wotton is the only one to have had his civil liberties constrained.

Outside the council chamber on Palm Island there is now a memorial to the seven men who led the 1957 strike against the oppressive reserve conditions of the Queensland Government. The inscription reads: 'In June 1957 seven men were arrested at gunpoint by police, during the night. (They) were herded like cattle onto a boat and sent to Townsville....These seven leaders were found guilty of triggering a long planned strike for better wages, food and housing. They also called for the removal of the superintendent. They were deported to other settlements from their home, Palm Island. The media repeated the government's opinion that a riot had been put down. The following inquiry found there had been no damage either to property or persons and the strikers had convincing grievances.' The struggle continues. But it is always good to remember those who confronted even greater challenges and in our own lifetimes.

The starting point for my reflections on faith and culture today is the speech of Pope John Paul II delivered at Alice Springs 26 years ago. No one would claim that the Pope's speech was a determinative catalyst accelerating the positive developments and putting a brake on the negative reversals in Australian church and society these last 26 years. But this speech still embodies the most noble shared aspirations of Aboriginal Catholics and those wanting to see Aborigines take their place in the Australian Church. The speech undoubtedly painted too rosy a picture of the role of the missionaries, glossing over the failings including assimilationist mindsets and the evil of sexual abuse. Only recently has the church come to appreciate its past failings in adopting assimilationist methods such as removing children from their families and placing them in dormitories, and in using English exclusively rather than local languages. The speech gives too optimistic a reading of the prospects of Aboriginal Australians taking their rightful place in the church without the likelihood of Aboriginal priests or bishops in the foreseeable future. The speech too simplistically glosses over some of the disconnection between Christianity and some of the core beliefs and practices of traditional Aboriginal religions.

It has been very helpful to have the Pope offer the encouragement that there need not be any conflict between Christian faith and Aboriginal culture. But Aboriginal culture is often founded on religious beliefs which find and express God's self-communication outside of Christ and the Church's seven sacraments. I recall a funeral of a well respected Aboriginal leader in the Kimberley. After the church service, the Elders took the body for ceremony which was no place for the priest or other outsiders. No participant presumed that the religious business had been confined to the church and that all that occurred thereafter was purely cultural. The body and its bearers moved seamlessly from one religious world to another, the bearers and the onlookers respecting the sacred space of each world.

The abiding grace of the Pope's speech is incarnated in those words in which he reverenced the Aboriginal identification with country and the daily Aboriginal reality of suffering and marginalisation. With papal reverence, he touched the deep Aboriginal sense of belonging, embracing the hope in their suffering. He conceded in the spoken word and by his charismatic presence that the Dreaming is real, sacramental and eternal. He retold the story of Genesis in Aboriginal voice. He relayed the calls of the post-exilic prophets to the contemporary powerbrokers and poor of Australia. He spoke poetically of things he knew not, knowing that those listening had endured the flames:

If you stay closely united, you are like a tree standing in the middle of a bush-fire sweeping through the timber. The leaves are scorched and the tough bark is scarred and burned; but inside the tree the sap is still flowing, and under the ground the roots are still strong. Like that tree you have endured the flames, and you still have the power to be reborn. The time for this rebirth is now!

Everyone present knew that he understood, and more than many who had spent a lifetime in this place. Two years ago, the Roman Catholic Church canonized the first Australian saint, Mary MacKillop, the founder of the Josephite sisters who have provided education and welfare services to the poor, especially in remote and rural parts of the vast Australian continent. Indigenous Australians played a key role in the celebrations. I was sitting with an Aboriginal group at the Mass of Thanksgiving at St Paul's Outside the Walls. Aboriginal dancers participated in the Offertory procession. Aboriginal deacon Boniface Perdjert assisted the Cardinal at the altar. The Aborigines around me were very proud of the Aboriginal participation in the liturgy. It was their participation which rendered the celebration most Australian, even for those of us who were not indigenous. Evelyn Parkin an Aboriginal woman originally from Stradbroke Island beamed a wonderful smile as she surmised about her people completing the circle: Italian missionaries had come and ministered to her people in 1843, establishing the Catholic Church's first mission to Aborigines. 167 years later, her people had come to Rome as people of faith proclaiming their faith to the Italians just as the Italians had done to them.

Before the mission was established on Stradbroke Island, the local Aboriginal community of 200 persons was forced to host more than 1000 convicts from the mainland. A prison was run there from 1831—1839. I daresay not all the convicts and their warders were easy-going beachcombers.

There is a plaque on the island commemorating the first recorded meeting between Aborigines and Europeans. Matthew Flinders was sailing past in 1803. He and his sailors were short of water. The Aboriginal traditional owners not only invited them ashore. They joyfully showed them where to find fresh water and farewelled them on their way.

The first missionaries arrived in 1843. Archbishop Bede Polding the English Benedictine had just returned from Rome where he convinced the Pope to establish the Australian hierarchy. He became the first Archbishop of Sydney. In Rome he had also convinced the Passionist Order to provide four men who could establish the Church's first mission to Aborigines. He had his eye on the talented well connected Fr Raimondo Vaccari who was 40 years of age and was said to be one who 'enjoyed great fame as a preacher, and had many influential friends among the laity, the upper ranks of the clergy, and the cardinals at the Vatican'. The Superior General was most unwilling to let this man go to the other end of the earth. But in the end, he surrendered to all those persons of influence. Vaccari was joined by Luigi Pesciaroli (aged 36), Maurizio Lencioni (28), and the French born Joseph Snell (40). They could speak no English but that did not matter; neither did the Aborigines.

Vaccari wrote to Polding saying that his men were 'free from anxiety and full of hope for the conversion of these my aboriginals'. We can all be forgiven for thinking that the language sounds more than a little patronising these days. The local people had obviously not lost their natural hospitality as displayed to Flinders 40 years before, despite the presence of so many convicts for so long. Vaccari reported to the Archbishop: 'They hold us in veneration and show us great affection, this being quite the reverse of their treatment of other Europeans, for, these, they say, do not act kindly towards them but betray them and deceive them, so that they have lost all confidence in them.'

Three years ago, we celebrated the establishment of the mission as part of the 150th anniversary of the colony (now State) of Queensland. One of the participants at the liturgy was Mrs Rose Borey. I will never forget her waiting for Pope John Paul II to walk down the Dreaming Track in 1986 when he came for the meeting with the Aboriginal people at Alice Springs. The organisers had been told that the Pope was not allowed to wear the Aboriginal colours. That was no problem. They vested him with a crocheted stole in the distinctive black, red and gold when he reached the track. He knew better than to take it off.

As he got close to us, Louise Pandella thrust her three month old son into his arms and he held the baby up to the skies with such love and respect. Rosie was jostling to get close. The tussles all around us made some of those manoeuvrings by nuns in the Vatican look orderly. But Rosie got there and presented the Pope with a framed copy of the Our Father in your local Gurumpul language.

She was so proud that a catechist descendant of the first Australians evangelised on Stradbroke Island was able to present the Lord's Prayer in language to the Pope. Fr Vaccari once told Archbishop Polding that the local Aboriginal people did admit the existence of a Supreme Being. They had told him, 'We have not yet spoken to Him, for He has not yet spoken to us; but we expect to see and speak to Him after death.' And now Evelyn Parkin was at St Paul's Outside the Walls expressing delight at being able to proclaim the gospel to the Italians.

Sitting behind Evelyn was Agnes from Kununurra in the Kimberley, the other side of the vast Australian continent. At the beginning of the liturgy she whispered to me: 'Father, this a sacred place?' I answered, 'Yes'. 'Then I could take off my shoes?' 'Of course', said I thinking of Moses at the burning bush:

So Moses said, 'I must turn aside now and see this marvelous sight, why the bush is not burned up.' When the Lord saw that he turned aside to look, God called to him from the midst of the bush and said, 'Moses, Moses!' And he said, 'Here I am.' Then He said, 'Do not come near here; remove your sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.' He said also, 'I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob ' Then Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God. (Exodus 3:3-6)

At the conclusion of the liturgy, some of the Aborigines invited those gathered around them to join them outside the entrance to the church. They had visited the church the previous day, concluding their researches and ascertaining the burial place of Francis Xavier Conaci. They led us in the most moving prayer for Francis, the Aboriginal boy who left Western Australia on 9 January 1849 for training as a Benedictine monk. Francis died on 17 September 1853 aged about thirteen and he lies buried outside the front of the basilica of St Paul Outside the Walls. Gathered around his burial place, we were moved to tears. The didgeridoo was played; a traditional dance was performed; Graeme Mundine and Elsie Heiss led the prayers; and Vicki Clark led the singing of 'The Old Wooden Cross' (the hymn which is sung at most Aboriginal funerals) and the Aboriginal Our Father.

Little is known about Conaci other than what is found in the memoirs of Bishop Salvado who departed for Europe with two Aboriginal boys on 9 January 1849. He had come to Perth from the New Norcia mission a hundred miles away in order to sell produce there.

The two boys had only been a couple of months in the Mission, so that when they reached Perth everything made them gape. But the thing that most astonished them was a boat — they thought it was a large fish or some animal that could walk on water! We could not manage to convince them that this animal was guided from the rear, for horses, they insisted, have the bit in their mouth and not in their tails (they thought the ropes attached to the rudder were reins). Then, when they saw the large ships, they thought they were the fathers of the boats, and wanted to know if these grew as big as the parent ships later on. Poor lads, everything was new to them!

He was then to stay on and offer the Christmas masses in Perth. No sooner had Salvado celebrated Christmas in Perth and the bishop Brady thought it would be best for Salvado to go to Europe given that a ship had arrived in port unexpectedly 'from Sydney on its way to Europe'. Salvado tried to argue his way out of it, but to no avail.

'When the two boys heard of my imminent departure, they begged me to obtain permission from the Bishop for them to go with me to Europe. The Bishop was happy to meet their eager wishes, and so I got the approval of their parents and made everything ready for the voyage. On 6 January the boys were baptized by the Bishop with the names of Francis Xavier Conaci and john Baptist Dirimera, which I had earlier given them at the Mission. The Secretary of the Colony, Dr R R Madden, and his wife were the godparents.' Salvado surmises that the tribal name 'Conaci' would have been bestowed by the father who traditionally would choose a name suggested by something that happened at the time of the birth. A black cockatoo (manaci) may well have passed by.

They departed Perth on 9 January 1849. On 17 April 1849, they reached the UK. One night in London, Dr Madden who also happened to have travelled on the same ship as Salvado, invited him 'to attend a meeting of learned and philanthropic men in which the subject of the Australian natives was to be discussed'. A letter from New South Wales describing the primitiveness of the natives was read out to the assembly. Salvado expressed a contrary view:

Some claimed that the Australian natives were incapable of intellectual formation, of understanding the benefits of civilisation, or the right of property, and there were other absurd statements which there would be no point in repeating here. My only answer was to trace the story of the Mission of New Norcia....and specious allegations simply collapsed before the facts.

They then went on to Paris where there was still civil disruption on the streets following the workers' revolt of the previous year. Soldiers were pursuing some rioters through the streets on 13 June 1849.

One of my boys, agitated by this extraordinary display, asked me what it was all about. I told him that some of those who had just rushed by shouting were bad men, and that the soldiers were going to fire on them if they failed to keep the peace.

'But I see', said the boy, 'that the others have rifles too. Who will win?'

'There are only a few of the bad men,' I replied, 'and so the soldiers will win.'

He was silent for a few minutes, and then he went on: 'Why don't you go between the soldiers and the bad men, take all their weapons away, and lock them up in this house and stop them from fighting — and the two of us will help you?'

'Because this is not my country, and I don't know anyone here', I replied.

'That doesn't matter. You don't belong to my country either, and you didn't know the natives, but when they were getting ready to fight or had already started, you went in among them, took their gidjis, shut them up in the Mission house and it was all over. Why don't you do the same here?' This argument, which was so much to the point and so unexpected from a boy who eight months before was wandering naked in the bush and was as uncivilized as only a native can be, left me bereft of a satisfactory reply. I did not want to tell him that in a case like this, it was easier to get good results from natives than from those who boasted they had reached the acme of civilisation.'

The boys were then delivered to the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Cava, Italy. The boys then entered the noviceship at Cava on 5 August 1849. When describing the physical and intellectual qualities of the Aborigines, Salvado quotes two letters he received from the boys. Francis was clearly progressing much better at his studies than was the older John Mary. Salvado was assured by their teacher that the boys had composed and written the letters themselves.

In the second letter, Francis wrote:

Your Lordship,

It is with great pleasure that we received your welcome letter, dated 1st July, by means of which we learnt that you are in good health, and we assure you that we are, too. We hope that your occupations will leave you free at least for a few days, so that we can have the consolation of seeing you again and kissing your hand.

To give you a proof of my behaviour in study, I send you a certificate that I got in the public examinations of September, with the mark 'Very Good', together with the silver medal, which the Father Master of Novices is keeping for me. We thank you for the picture cards of saints that you have sent us, and we ask you to bring a little book of prayers containing Preparation for Holy Communion. We kiss your hands affectionately, as do all my comrades, especially Brother Silvano. Asking your holy blessing,

I am

Your affectionate son in Christ,

Francis Xavier Conaci

The translator E J Stormon SJ notes that a comparison of a facsimile of the original letter with Salvado's translation reveals that 'Salvado has tactfully omitted a couple of sentences in which Francis rather lords it over his companion John, who so far has not learned to read, and can only copy out set handwriting.' The Novice Master added a note to Salvado: 'The above letter, composed and written by the boy himself, shows how proud he is, and how little attention he pays.'

Having quoted these two letters, Salvado concludes his chapter on the physical and intellectual qualities of the natives with the observation: 'I think I have said enough by way of proof of the physical and moral character of the Australian natives.'

When Francis fell ill at La Cava, he was taken to St Paul's Outside the Walls to take the fresher air. There he died on 17 September 1853; and there he was buried. John did not fall gravely ill until May 1855 whereupon he was returned to Australia, dying three months after his return on 21 August 1855.

Many of us who had arrived at St Paul's Outside the Walls knew nothing of this story. The simple Aboriginal ritual over the burial site of Conaci was in stark contrast to the pomp and hierarchical ceremony in St Peter's Square the previous day. Here were indigenous people not only finding voice but leading those of us who are the descendants of their colonizers, teaching us the history, sharing the story, and enabling us to embrace the mystery of it all in prayer. Our role was to follow, to join in prayer and to express thanks for the gracious sharing and leadership of the indigenous people.

Two nights before the canonisation the Vatican Museum opened a display of Aboriginal artifacts and works of art which had been sent from the missions to the museum in 1925. Indigenous Australians placed their indelible mark on proceedings with song and dance in the Vatican Gardens. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholics from across the land mixed with bishops, donors, politicians and pilgrims accompanying the Josephite sisters wearing not brown veils but their light blue pilgrim scarves. William Barton on the didgeridoo joined his mother Delmae and a string quartet under the lights of the dome of St Peters. Four years previously Delmae had lain uncomforted with a stroke at a university bus stop for hours as hundreds passed her by, prompting a national reflection reminiscent of the parable of the Good Samaritan. This night she and her son gave all Australians a place of belonging in this sacred place. The Vatican Museum put on display Aboriginal art sent from the missions back in 1925, predating by 50 years most of the Aboriginal art on display in galleries back home.

Just before going to Rome, I had the chance to check out the wonderful new galleries at the National Gallery in Canberra. They are spacious, making great use of natural light. In one gallery, there are two paintings by the late Hector Jandany from Warmun in the Kimberley. One painting is entitled 'The Ascension', and the other is entitled 'Holy Spirit in this Land'. Hector's description of 'The Ascension' appears in the gallery catalogue:

The two spirits on the right make the fire; the two spirits on the left get the meal of fish ready; Jesus' friends (are) at the bottom of the picture.

Jesus said: 'We all have supper; This is my last day I have supper with you, I got to go away, I go longa way 'Ngapuny Ngarrangkarrinjl'.'

His friends did not know that the fire would make a big smoke.

It make a big smoke and come up behind the hill and took Jesus up to Heaven.

That smoke bin come and lift him up and take him away to Heaven.

Hector was encouraged to paint in his home community by the Josephite sisters who had established a spirituality centre nearby. They also ran the community school and assisted at the old people's home. The sisters were not trained anthropologists or art advisers. Like Mary MacKillop they came amongst the poor in a remote area, shared what they had, educating the children and encouraging the adults. None of the sisters would claim any of the credit for the art of Hector and his school of Turkey Creek painters. But for the sisters' presence at Warmun all those years, I doubt that Hector's paintings would now be hanging in the National Gallery. His Holy Spirit painting is now replicated in a huge and majestic mosaic at the Australian Centre of Christianity and Culture. But for the selfless dedication of the sisters all these years throughout Australia, I doubt that there would have been 8,000 Australians in St Peter's Square two years ago attesting the holiness of Mary Mackillop.

Such celebrations confirm that indigenous identity is still strong and resilient though ever adapting for individuals and communities who have endured much by way of dispossession, dislocation and disempowerment.

With a confident identity and secure sense of belonging in both worlds, indigenous people might 'gradually banish the painful sense of being separated from their ancient connections'. Those citizens who are recent migrants are joined with the descendants of the colonisers, accepting the national responsibility of correcting past wrongs so that the descendants of the land's traditional owners might belong to their land, their kin and their Dreaming in the society built upon their dispossession.

For many indigenous people, the attempt to live between two worlds is too difficult. A reason to live, a reason to live well, a way to live authentically eludes them. Jonathan Lear's book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation provides reflections of universal import on the life of Plenty Coups, the last great chief of the Crow Nation. Plenty Coups had shared his life story with a white hunter Frank Linderman who had settled in Montana at the end of the nineteenth century. Lear, a philosopher from the University of Chicago, was haunted by Linderman's note at the end of his book:

Plenty Coups refused to speak of his life after the passing of the buffalo, so that his story seems to have been broken off, leaving many years unaccounted for. 'I have not told you half of what happened when I was young', he said, when urged to go on. 'I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. Besides,' he added sorrowfully, 'you know that part of my life as well as I do. You saw what happened to us when the buffalo went away.'

I happened to be reading Lear's book on my trip to Rome at the time of the canonisation. Its resonances contributed to my tears when the Aborigines led the simple ceremony at the grave of Conaci. They had reclaimed his story. His story was a vehicle for communicating their own ongoing struggle with straddling the divide of belonging and meaning. Their liturgy provided the means for communicating meaning, dignity and hope despite all that has occurred. Reflecting on Plenty Coups' vindication of life, Lear says:

Plenty Coups' dream — and his fidelity to it — also enabled him to live what Aristotle would call a complete life. In spite of the devastation to traditional Crow life, Plenty Coups's dream became a thread through which he could lead his people through radical discontinuity: and at the end of his biological life, he was able to see his life as having a unity and a purpose that was confirmed by the unfolding of events. Indeed, the repetition of his story to Linderman is its completion. In telling his story, he presented himself as having a complete life; and he was able to pass on to a future generation what he thought was still essential to the Crow way of life.

At the liturgy at St Paul's Outside the Walls, some Aborigines thanked me for accompanying them and for sitting with them during the Mass. I would not wanted to have sat anywhere else. It was such a privilege to share the fullest liturgical expression of indigeneity colouring and leavening the universal, globalised Roman ritual. They, and only they, are able to bridge the radical discontinuity of their lives and history, finding a place of belonging in a globalised world where the Market can attribute value to everything, except that which is most important and valuable to the human person — that radical hope which allows us to weather the worst storms of the Market in all its manifestations. Indigenous people know this better than most of us because they have endured the market forces of empire which denied the value of all that their ancestors held dear. Thank you for all you NATSICC members do to show us whitefellas a culturally enriched living and proclamation of the Gospel.

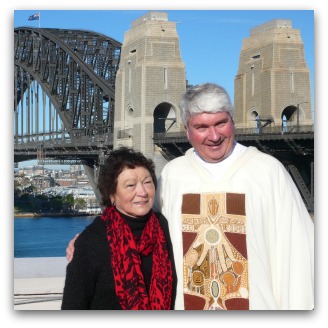

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's address 'Culturally Enriched Through the Gospel' at the NATSICC Conference, Bell Rydges, Preston, on 1 October 2012. Photo: Fr Frank Brennan with Elsie Heiss, Leader, Aboriginal Catholic Ministry, Sydney.

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's address 'Culturally Enriched Through the Gospel' at the NATSICC Conference, Bell Rydges, Preston, on 1 October 2012. Photo: Fr Frank Brennan with Elsie Heiss, Leader, Aboriginal Catholic Ministry, Sydney.