I am riding my bike, a little book tucked into the front basket along with a hat and a pair of scissors. I am on my way to the local community garden, and even though I don’t have a membership I feel optimistic about finding some food. The book is entitled The Weed Forager’s Handbook, and it is all about finding weeds you can eat.

In the damp shade of a passionfruit vine, I kneel on the ground and lean in closely to inspect a specimen. A green leaf with jagged edges. A wild lettuce, perhaps? No, it lacks the hairs on its underbelly spine. Dandelion? Seems to be growing a little too upright for that. I leaf through the pages of my little field manual, pouring over photographs and descriptions. Ah, there it is! A sow thistle! More vertical than a dandelion, spikey leaves that despite the name aren’t all that prickly, and a milky sap that exudes when you snap any part of it. I put a tiny piece in my mouth and chew. Kind of mild and green-tasting, like spinach maybe, accompanied by a warm sense of satisfaction that I have a vital new piece of knowledge about my local, natural world and its ability to sustain me. I am hooked.

I soon develop a habit of scouring every nature strip, front yard or roadside greenery with my eyes, the way I am accustomed to casting my gaze over market stalls or shopfronts for things to buy. But unlike at the mall, these weeds, these edible plants, are entirely free. I learn that mallow grows well in the bare patches of garden beds, often over the top of tanbark, spreading its long, leaf-star arms in all directions. Purslane gives me a special thrill when I notice it bursting forth from the cracks in pavements, where it especially likes to abide, its little sour leaves all plump and glistening. And the dandelion pops up, lush and cheerful, in any place it has an opportunity: the edges of walls seem to be a particular favourite (it’s where their little parachute seeds get caught and fall), but also front yards, alleyways and sides of roads everywhere – and of course, lawns.

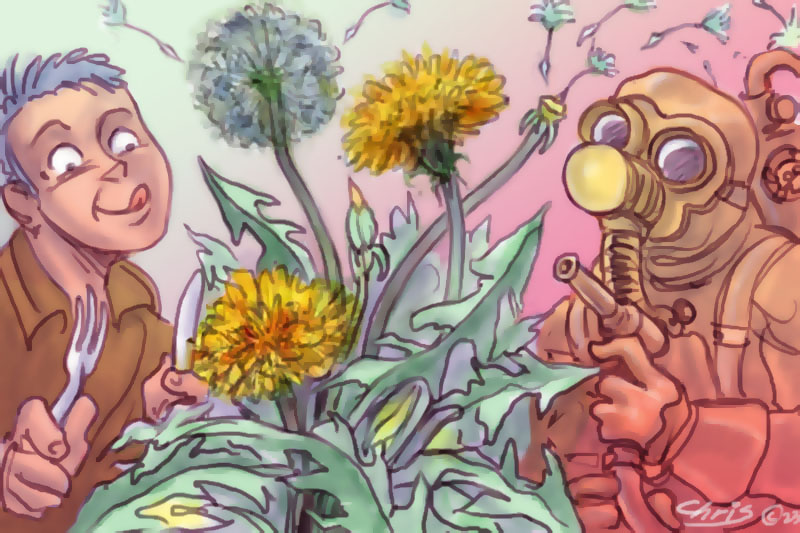

Dandelions are Public Enemy No. 1 with lawn owners everywhere, and millions of dollars are spent annually on herbicides to dispense of the hardy plants. But, I discover, in times gone by, dandelions were so prized for their beauty, nutritional content and cure-all medicinal value that they were cultivated as a garden plant, and intentionally brought from Europe to places like America and Australia amongst other carefully packaged garden seeds. But we went from love to loath in a matter of a generation. And, I discover, the reason for this has a lot to do with lawns.

Lawns used to be the purview of the landed gentry – after all, only the very wealthy could dedicate such large swaths of land to such an unproductive use as growing grass, as opposed to crops. The status symbol of the lawn has not gone away but has simply become more accessible; these days, it is wrapped up in the Australian dream of home ownership: a detached house in the suburbs for your family and dog, with a lawn at the front and back.

The idealised lawn is a monoculture of grass, and Australians are so dedicated to ensuring they stay weed-free that a whole range of herbicides are used to knock out unwanted intruders. One product advertised online is apparently registered to destroy twelve different kinds of weeds that might be inclined to pop up on your lawn. Yet most of the plants listed have only in recent times been considered weeds at all: six of them are edible, and at least a further two are known for their medicinal value.

'There are gifts all around us, literally sprouting from our streets: living invitations to re-find who we are, as creatures in relationship with the land, finding connection and sustenance outside of what the market provides.'

Instead of living alongside and utilising these plants, we have come to a strange point in history where our instinct is to wage war. And it is a violent war: each year, tonnes of plant-killing chemicals are poured onto lawns around the country, poisoning not only the plants but the insects and birds that feed off them, and the fish when they end up in our waterways. It is hard to imagine how the chemicals are not within our bodies as well.

Yet before widespread urbanisation, rather than dousing the land with chemicals to grow soft and uniform lawns, people relied on the land on which they were living to provide their daily sustenance. Food was not something you went down to the local supermarket to buy, in pristine plastic packaging, but was something you or your neighbours grew, cultivated, nurtured, foraged. Food – and medicine – included mallow, sow thistle, dandelion, plantain, fat hen, chickweed and more… all the target of lawn weed killers, today.

Tumultuous historical events have broken our once-deep belonging to land – the industrial revolution, urbanisation, colonialism. Instead of the land, we have turned to the market to provide our daily sustenance. We don’t need plants anymore: we have supermarkets, restaurants and pharmacies. Plants that once kept us alive have now become despised weeds.

And yet, I have discovered that despite our greatest efforts, the weeds are winning. They are coming up between the cracks, on the edges of laneways and in the corners of playgrounds. It turns out that, if you look at things a bit differently, we live in an urban food forest! You have to be choosey about where you pick your weeds, but if you develop a relationship with local councils, neighbours or schools, or have a backyard, there is free, organic produce to be picked all over the place.

Walking back from the library, I spy a rosette of dandelion leaves bristling between footpath and the edge of a front yard, as green and fresh-looking as a head of lettuce. There aren’t any flowers yet but I recognise the jagged, ‘lion’s tooth’ leaves, and feel satisfied that I now know this plant in its many iterations of life-cycle. I wonder if this is the beginning of my own ‘re-wilding’ – a process of re-finding my connection to land and place. Re-wilding is something of a movement. My hairdresser is a re-wilding enthusiast and goes for week-long solo retreats in the bush, finding her place again as an earthly being. But in my own way, I’m doing it here in the city, tapping into parts of my genetic makeup adapted to knowing the sight of edible plants, and the way they feel in my fingers. I am beginning to live a little more like the way my ancestors lived; a little more wild, even though this jungle is an urban one.

.png)

I pluck a few of the young, tender leaves off the dandelion plant and put it in my shoulder bag, wondering about a salad, or maybe some tea. I’m struck by the realisation that there are gifts all around us, literally sprouting from our streets; living invitations to re-find who we are, as creatures in relationship with the land, finding connection and sustenance outside of what the market provides. The food we find here is wild and free, and there is the possibility that we might become that, too.

Andreana Reale is a Melbourne-based writer and currently a candidate for ordination in the Uniting Church.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.