Just as universe of referendums seemed to have been exhaustively mapped last year, the recent Irish Referendum shot across the sky like a comet. It had many features in common with the Referendum on the Voice, and was even more decisively rejected. It also clarified the conditions necessary for a Referendum to succeed.

The Irish Referendum echoed the Australian one in seeking to change the Constitution. It also sought to ride a perceived wave of change in social attitudes to marriage and the family. The two proposals made in the Irish referendum concerned the relationship between marriage, the family and society. The first broadens the understanding of the family by adding the italicised words:

The State recognises the Family, whether founded on marriage or on other durable relationships, as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society.

It also removes the connection between marriage and family by deleting the bolded phrase:

The State pledges itself to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, on which the Family is founded…

The second proposal in the Referendum also qualified the emphases in the Constitution both on the importance of the work of women in the home for the common good, and on the duty of the State to ensure that economic necessities did not force women to work outside the home.

The clauses in the Constitution replaced in the Referendum were:

The State recognises that the provision of care, by members of a family to one another by reason of the bonds that exist among them, gives to Society a support without which the common good cannot be achieved, and shall strive to support such provision.

In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.

The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

These clauses were replaced by the statement:

The State recognises that the provision of care, by members of a family to one another by reason of the bonds that exist among them, gives to Society a support without which the common good cannot be achieved, and shall strive to support such provision.

As in the Australian Referendum the Irish Government believed that public attitudes supported the changes to the Constitution. The sweeping majorities for Referendums to legalise gay marriage and abortion suggested that a similarly liberal change to weaken the necessary connection between family and marriage and to make the support of the family more diffuse and not tied to the specific work of women at home, would be generally accepted. The initial polls supported this view, and all the major Parties were in favour of its passing. And yet both proposals were rejected by about 70 per cent of the voters, a margin greater than in the Australian Referendum.

px.jpg)

The reasons given by Irish commentators for the failure were much the same as those canvassed in the Australian case, with the exception that the Irish Referendum did enjoy multi-party support. Some saw in the failure the revenge of conservative social attitudes endorsed by populist public figures. They noted that the referendum proposals were opposed by the Catholic Bishops on the grounds that it failed to recognise specifically the importance of families (the largest social group caring for children), the contribution made by mothers at home, and the Government responsibility to care for families. Many advocates for disability rights also campaigned against the second provision on care. They feared that government would use the general wording to weaken its responsibility to care for them. There was thus some fracture in the support for the Referendum.

'This suggests that, as a minimum requirement, all major political parties must support the Referendum. That is a necessary condition for its passing. The Irish example shows, however, that it is not sufficient. It must also have the support of many major community groups such as churches, ethnic communities and activist associations.'

Most commentators noted that the second proposition about care was complex and aspirational. It replaced precise and narrow provisions in the Constitution, and particularly the requirement that the Government ‘endeavour to ensure’ that economic hardship not compel women to work outside the home. The substituted paragraph was seen to offer a number of different interpretations.

The Government was also criticised for not consulting widely on the wording of the proposal. That seemed a little unfair. In Ireland referendums must be preceded by a Citizens Assembly composed of randomly chosen citizens. The Government accepted the amendments proposed by the Assembly and submitted them to Parliament. To have varied them would surely have subjected it to accusations of manipulation.

A comparison of the Irish and Australian referendums suggests that No is the default position. People are habitually and notably bolshie when asked to participate in Referendums. Their first instinct is to distrust Governments, fearing that they will use changes to the Constitution to increase their power or to shed their responsibilities. There is an inbuilt negative vote by those who are suspicious of change, regardless of the issues involved. In order to succeed, Referendums will require very strong public support.

This suggests that, as a minimum requirement, all major political parties must support the Referendum. That is a necessary condition for its passing. The Irish example shows, however, that it is not sufficient. It must also have the support of many major community groups such as churches, ethnic communities and activist associations.

Second, the wording of any Referendum must be simple and clear in its consequences. Any political proposal will attract and give a voice to rhetorically gifted opponents and draw city and bush lawyers like bees to honey. Ambiguities and uncertainties about the meaning and scope of the change to the Constitution will strengthen the natural resistance to change. The amendment to the second Irish proposal was conspicuously vague, replacing concrete commitments with ideals.

Third, the referendum must seem to be timely and to express the will of the people. Voters must see it as a natural expression of what the nation now clearly needs. This is clearly hard to judge. Both Antony Albanese and Leo Varadkar had good reasons for believing that this consensus was there.

Equally important, however, people must also believe that the nation faces no immediate higher demands to which the Government must attend. Where people feel the pressure of high prices, lack of accommodation, high interest rates and international challenges, they are likely to punish a government distracted by holding a Referendum. This appears to have been a common and perhaps decisive factor in the Australian and Irish Referendums.

For this reason it would be rash to assume that a failed referendum implies rejection of the aspirations of the persons it was designed to support. Irish women seeking affirmation for a wider understanding of family and of women’s place in society, and Indigenous Australians seeking recognition, equality and a voice in decisions that concern them will rightly be disappointed by the failure of the Referendum. Their causes, however, do have widespread support in the community. The challenge will be to embed that support in the institutions that affect people’s lives directly. Constitutional change must wait until it is seen as natural, simple and timely.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

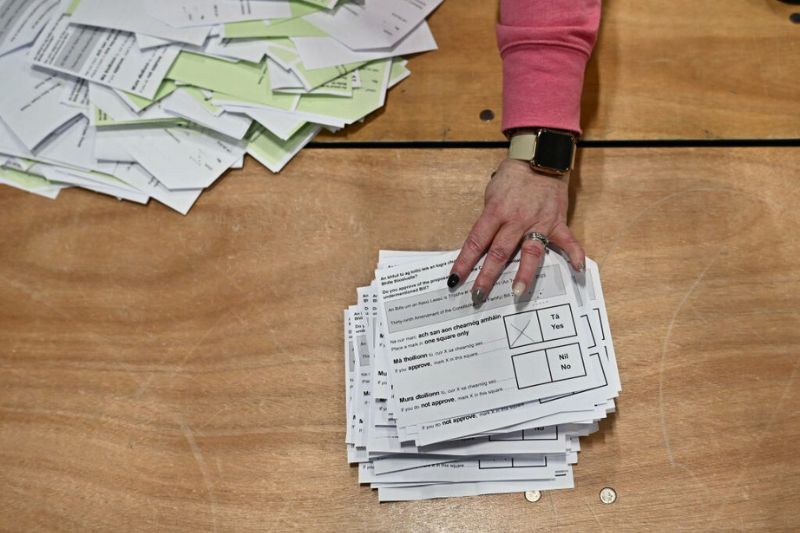

Main image: Votes are counted following the Referendum at the RDS Dublin Count centre on March 9, 2024 in Dublin, Ireland. (Photo by Charles McQuillan/Getty Images)