My mother seemed to have a song for every occasion. At this stage I think I am close to matching her with quotations, as so many stick to what I describe as my fly-paper mind. (An Englishman once suggested that ‘a jackdaw mind’ is more upmarket, yet somehow the idea of flypaper is still with me.) But every so often the little items urge me to investigate whole works and the lives of those who produced them: so it was with William Cowper’s very long poem The Task.

Cowper, a poet who preceded the Romantics and whose life spanned most of the eighteenth century, was a troubled soul. Son of a clergyman, he lost his mother when he was only five, and this blow was one from which he apparently never really recovered. He was mentally unstable throughout his life and spent time in institutions for those with such afflictions. He feared that he was condemned to hell, and that God had commanded him to commit suicide. Fortunately, he was given consistent help by excellent friends.

One friend was John Newton, author of the hymn Amazing Grace, and a fervent Abolitionist. Cowper predictably became an Abolitionist, too, and he and Newton collaborated on the composition of a hymn book, for which Cowper wrote 68 hymns, including the one that tells us that God moves in mysterious ways. He also became famous as a poet and was commissioned to write a poem in blank verse, which turned into the six parts that make up The Task.

It is the second part of this poem that is my preoccupation at present. When I was very young, the Bomb was uppermost in my mind. Added to that worry was my fundamentalist grandmother’s rather relished anticipation of the end of the world: she contributed to my becoming a teenage insomniac. My father did his best to rescue me, pointing out that such fears had been around for a very long time. He pointed out developments such as the replacement of the crossbow by the long bow and the invention of gunpowder.

Much later, I am still worried by the various threats to the world, ones that are unfolding at an ever-increasing rate. My eldest son has told me that for one whole year he did not watch television, listen to the radio or read a newspaper, and felt much better for not engaging with the world via media. I can well believe this and have cut down on the number of times I watch the news or read a paper. But I still feel compelled to tune in at least to a certain degree, even though I know I am going to be shocked and horrified by the latest actions of the various crooked characters exercising power at present.

But Cowper’s words, published in 1785, strike a chord, they really do. He tells the reader of a longing for

Some boundless contiguity of shade/Where rumour of oppression and deceit/ Of unsuccessful or successful war/Might never reach me more! / My ear is pained/ My soul is sick with every day’s report/Of wrong and outrage…

Exactly: Cowper’s thoughts show that my father was of course right about world-threatening problems always being part of existence, although we understand that the application of science has tended to make these threats much worse during the last century and in the first quarter of this one. And like countless generations before us, we still worry about the future of our children and grandchildren.

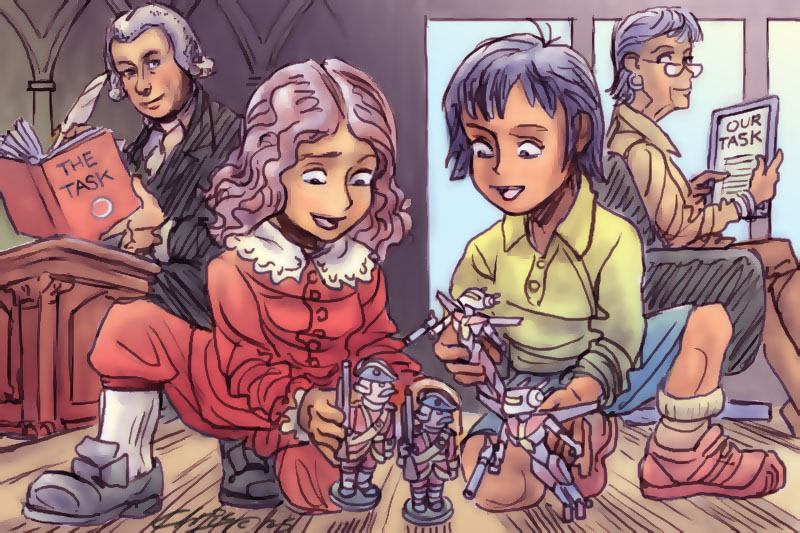

The church that I attended as a child had a tradition of holding what were known as Pleasant Sunday Afternoons. Ladies brought a plate, the supply of tea was endless, whole families came, people mingled and chatted, and there was entertainment in the form of piano solos and sung items. My mother (I can see her now) would occasionally sing the The Holy City, a popular Victorian song, but her favourite number was My Task, which was very much suited to her clear soprano voice, and to sentiments that were still alive decades after the song had been composed in 1913. One’s duty is clearly set out to the accompaniment of a stirring tune.

The emphasis is on truth, love and helping children. Other instructions are 'To ponder o’er a noble thought and pray…And smile when evening falls…To do my best from dawn of day till night.'

And it is also our duty to keep on trying, not to give way to despair. That is our task, for the present and for the foreseeable future.

Gillian Bouras is an expatriate Australian writer who has written several books, stories and articles, many of them dealing with her experiences as an Australian woman in Greece.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.