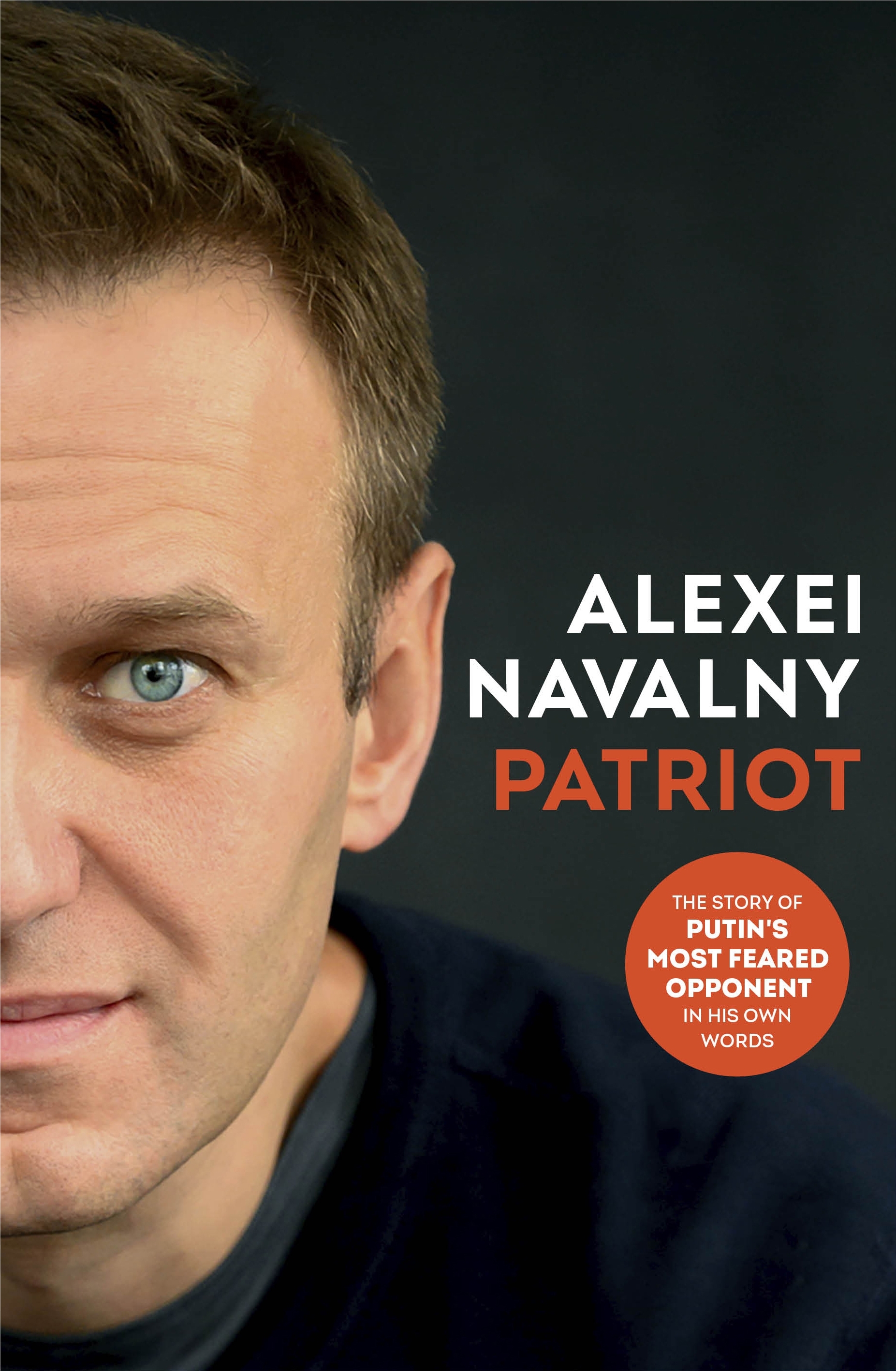

Last February, Alexei Navalny (1976-2024), a Russian political dissident and anti-corruption campaigner, perished in a remote, high security prison in the Arctic Circle. He was serving out multiple sentences on trumped up charges. Navalny’s memoir Patriot was released last month. Written in prison, it is a testament to Navalny’s deliberate practice of a forward-looking hope for the future, even though he was certain that he would not outlive his sentences. Surprisingly, the book is full of humour.

Even before he was imprisoned, Navalny was using humour to expose the absurdities of authoritarian power. Navalny ran the Anti-Corruption Foundation, and he and his team used social media to expose absurd displays of wealth by corrupt politicians. He began to make regular anti-corruption videos after discovering that the deputy prime minister Igor Shuvalov used his business jet to transport his pet corgis, separately, to international dog shows. Navalny notes that ‘we simply had to make a film about it’, and that would involve hiring a special ‘corgi actor, a lovely little dog that lay very obediently on the table next to me while I was talking about Shuvalev’.

Even though TikTok sometimes makes Navalny feel ‘ashamed for the whole of humanity’, like a grumpy grandad, he agrees to dance and (pretend) to sing in TikTok videos because that is where many viewers get their news about politics. Because it’s all such serious business Navalny even relents to the ‘torture’ of Instagram, where he learns that women, in fact, are tougher and more persistent that men.

Humour can indeed be politically subversive. The life and work of Mikhail Bakhtin, another Russian, somewhat ironically points to this. Mikhail Bakhtin, known for his discussion of ‘carnivalesque’ folk humour, also suffered under an authoritarian regime. Many of Bakhtin’s literary friends disappeared during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s, and he spent six years in forced exile in Kazakhstan. Much of Bakhtin’s research was repressed or ‘lost’, and the government was so uneasy about his thesis on literature and folk culture that it stepped in after prolonged debate and stormy faculty meetings to deny Bakhtin a full doctorate for his work.

Bakhtin drew attention to literary allusions to the carnivalesque goings-on of medieval feast days, such as the Feast of Fools. On these days hierarchies were upended, and playful dress-ups exaggerated and played back to the authorities how they were perceived by the everyday folk. These displays also functioned as pointed critiques of the corruption and hedonistic excess of those in power. Sound familiar?

Like Bakhtin, Navalny experiences several instances where his writing in prison is repressed or ‘lost’ by authorities. Navalny’s readers are ushered into the absurdity of his writing practice, where he knows in prison that others know that he knows that he is being watched as he writes. Thus it is all the more remarkable when we consider what emerges from the pages. What is smuggled out of prison bleakness, is a fresh, playful and humorous character who is keen to share his secrets to cultivating a ‘prison Zen’, such that his jailer puzzles that ‘you don’t look to me to be all that upset’ during the ‘really annoying full strip search’.

This prison Zen is nurtured by Navalny’s humorous outlook, which links to a self-deprecatory and ironic spirituality in jail. Navalny makes fun of himself by joking that his spartan cell and its privations is ‘basically Vipassana. It’s a spiritual practice for rich people suffering from a midlife crisis.’ He memorises sections of Hamlet while learning to sew in a prison class. When the inmates on his shift say that his closed eyes and muttered soliloquies make it look like he is summoning a demon, Navalny notes that he has no such intentions : ‘summoning a demon would be against prison regulations’.

Navalny says his job is to ‘seek the kingdom of God and his righteousness’. He knows that this job positions him automatically as a fool in the eyes of many, such that ‘you may roll your eyes heavenward when you hear it’.

Navalny sees many prison events as comforting, divinely-provided signs of hope and also as ridiculous, at the same time. He accepts a card from a grumpy and aloof inmate suffering from religious mania and is touched that the angelic representation on the card reminds him that he is not alone, even though the giver immediately turns away with the ‘familiar expression of indifference and mild irritation’. Navalny is so pumped that he feels like going over to the surveillance camera and thrusting the card into the lens, shouting ‘See you bastards, I am not alone!’

In the late 1960s Harvey Cox, an American theologian, said in his book The Feast of Fools that we need to move beyond all convention and clothe Jesus Christ in a clownsuit, because ‘only by learning to laugh at the hopelessness around us can we touch the hem of hope.’

Navalny was willing to put on a social media clownsuit to expose the ridiculous feasting of the fools in power. In prison, he also laughed at himself, a holy fool finding joy in a cell. Navalny can do this because the Jesus that he takes so seriously is also somewhat clownish: the ‘good old Jesus’ that Navalny describes in the closing paragraph of his memoir. Navalny imagines Jesus as a fellow prisoner, taking comfort in the fact that Jesus ‘will take my punches for me’.

Navalny says his job is to ‘seek the kingdom of God and his righteousness’. He knows that this job positions him automatically as a fool in the eyes of many, such that ‘you may roll your eyes heavenward when you hear it’.

The Apostle Paul, another Jesus-follower, who also spent some time in the jail cell of a brutal regime wrote that ‘God chose the foolish things of this world to put the wise to shame. He chose the weak things of this world to put the powerful to shame’ (1 Corinthians 1:27). Navalny’s holy foolishness reminds us that comic relief can help us catch a ‘glimpse of another world impinging on this one, upsetting its rules and practices’ (Cox, Feast of Fools), and that even though Navalny knew that he would not survive jail, he also knew that the Putinist state will ‘… crumble and collapse … One day, we will look at it, and it won’t be there’.

Danielle Terceiro is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and it completing her PhD at Alpha Crucis University College in Literature and Theology.