He always had a high opinion of himself, and it was one he managed to market to supreme effect. But Henry A. Kissinger, former National Security Advisor and US Secretary of State and now centenarian, was a practitioner of the darker arts of statecraft and diplomacy. An advocate of realism, he left his mark on several continents, playing a role in destabilising governments and regimes, and up-ending international law when he thought it necessary.

The last part is of much interest, if only suggesting that this scion of the US foreign policy establishment showed that a rules-based international order was a chimerical notion before the self-interest of great powers. Making much of his refugee status (he fled Nazi Germany in 1938), he advertised himself as one who had learned the lessons of Hitler’s Germany. His book, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-1822 (1957), initiated him as a ‘realist’ tinged with idealism, an admixture the historian Greg Grandin calls ‘imperial existentialism’.

Concerned with the Europe of the wily diplomat Prince Clemens von Metternich, Kissinger came to believe in an international system of balance, oiled by a decent amount of terror. The fair and the just had little role to play in this scheme; durability of a stable order was what counted.

This became an obsession, so much so that world politics became a matter of systems and adjustments, rather than blood and loss. The Cold War, with its risk of thermonuclear annihilation between the US and USSR, could itself generate a suitable balance of terror. Democratic experiments, certainly of the socialist variety, could go hang. In that sense, realism faced its own limits, being accused of being adjustable, malleable and a concept that could stand for everything.

That said, Kissinger has entranced historians and critics. Historian Niall Ferguson, punting from the conservative angle, is effusive about a figure who evolves: the raw material idealist who gets lucky with the granite pragmatism of the Nixon presidency after foiled and misguided attachments. Barry Gewen goes so far as to claim that Kissinger’s approach to international affairs ‘runs so counter to what Americans believe or wish to believe.’ For all that, Kissinger could still endorse the ultimate goals of the country, and imperium, that became his home. ‘A capitalist society, or, what is more interesting to me, a free society,’ he claimed in an interview in 1958, ‘is a more revolutionary phenomenon than nineteenth-century socialism.’ Realism, it would seem, could be pursued within a certain idealistic framework.

In the shadow of such thinking was Metternich’s fashioned legacy, whose role, alongside British Foreign Secretary, Viscount Robert Stewart Castlereagh, was to construct a post-Napoleonic Europe suspicious of democratic revolutions and freedom movements. As a result, Kissinger reasons, Europe maintained – with various stutters – continental stability from 1815 to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Even with that sense of achievement, Kissinger had to concede that Metternich lacked ‘the ability to contemplate an abyss, not with the detachment of a scientist, but as a challenge to overcome – or perish in the process.’ Without realising it, he enunciated a prophecy: ‘For men become myths, not by what they know, nor even by wat they achieve, but the tasks they set themselves.’

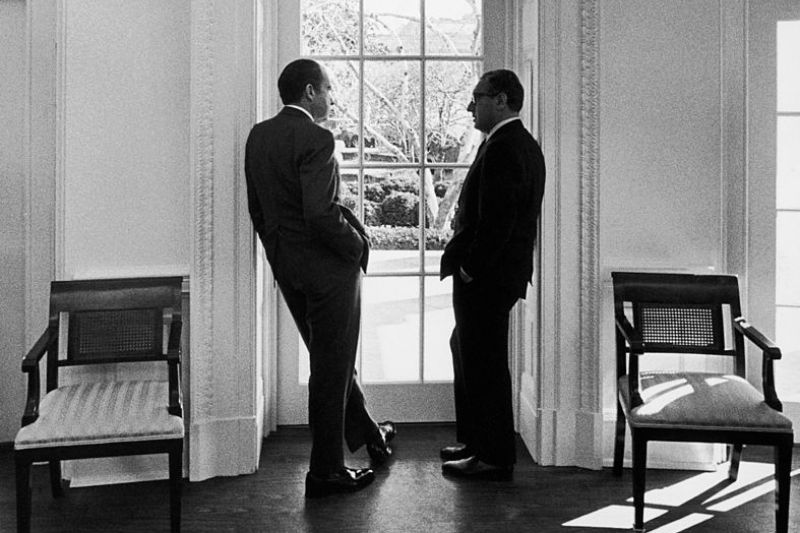

Kissinger’s partnership with President Richard Nixon became something of a mirror of this project, one ruthless, amoral and sanguinary. While international relations theorists could only see theories and models of power, dictators, strongmen and the autocrats wreaked havoc over countries, murdering, torturing and disappearing their citizens.

'Kissinger was one of the first, along with Nixon, to concede that the US, for all its power, could not sustain it indefinitely. The pieces would have to be reordered.'

Nixon sought Kissinger’s apprenticeship in the lead-up to the 1968 Vietnam peace talks orchestrated by the Johnson administration. As Republican presidential candidate, Nixon did not wish the Democrats to be getting any kudos for brokering peace in the Indochina conflict. With Kissinger reprised as a twentieth century Iago, he convinced the South Vietnamese that better terms could be reached under a Nixon administration. Sit tight and wait till the election result. The talks duly collapsed, prolonging the war for another seven years. In a grotesque twist, Kissinger received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 for negotiating a non-existent peace that eventually led to the triumph of the North Vietnamese two years later. The brainchild of ‘Vietnamisation’, which saw the US withdraw its own forces, leaving South Vietnam to do the heavy lifting with US equipment and training, showed the limits of the Kissingerian world view. Much the same formula was used in the wake of the US retreat from Afghanistan in August 2021.

With Nixon in the White House, the question remained as to how the North Vietnamese might be encouraged to return to the diplomatic table. This, thought the Machiavellian duo, could be achieved by conducting a secret bombing campaign of Hanoi’s supply routes in Laos and Cambodia. When the covert bombing program was exposed by the New York Times on May 9, 1969, Kissinger hounded the FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to place a number of selected government officials and journalists under surveillance.

On the ground, the bombing campaign cost some 150,000 lives, with recent reports suggesting that the violence may have been greater than initially thought, involving the use of helicopter gunships and ground operations by US and allied troops. The covert approach, one evading public scrutiny and Congress, became the blueprint for future military strikes, including the US drone program.

The signature contribution of Kissinger as a student suspicious of democratic movements came in his instrumental role in overthrowing Chile’s socialist President Salvador Allende. Just over a week after Allende’s election in September 1970, CIA director Richard Helms was told that, ‘We will not let Chile go down the drain.’

In November, Kissinger, refusing to accept local conditions in the country, warned that Allende’s election would provide an all too encouraging example for ‘the rest of Latin America and the developing world; on what our future position will be in the hemisphere; and on the larger world picture’. This was a model whose ‘effect can be insidious.’

When one considers the Kissinger ledger of lives lost, from the Vietnam War to Cambodia, East Timor, Bangladesh, the ‘dirty wars’ of Latin America he did so much to encourage, and a number of interventions in Africa, Grandin’s estimate comes to 3 million.

Beyond this, however, other motivations came through, befitting the refashioned guise of Metternich. The small country disasters of US interventions could be ignored in favour of the grand show: putting out the feelers to the China of Mao Zedong; teasing and tormenting the divisions between Moscow and Beijing. Finally, those in Washington had a sense, contrary to a view held since the Truman administration, that the Communist bloc was not monolithic but potentially fractious. By bringing in Communist China from the diplomatic cold, at the expense of Taiwan, a cleavage within the World Revolutionary Bloc might be exploited. In doing so, Kissinger was one of the first, along with Nixon, to concede that the US, for all its power, could not sustain it indefinitely. The pieces would have to be reordered.

Given such a record, it should come as no surprise that the still fully engaged consultant to governments and companies would abhor the International Criminal Court. Such a body risked entrenching a ‘dictatorship of the virtuous’ and a ‘tyranny of judges’. It exemplified Kissinger’s belief that statecraft was best done unshackled, to be conducted with impunity as to consequences.

Amidst the gushing birthday tributes and whitewashing omissions lie a stretch of efforts, and commentary, demanding that Kissinger account for his actions during his eight years in office. In a powerful polemic written in 2001, the late Christopher Hitchens argued that Kissinger’s ‘own lonely impunity is rank; it smells to heaven.’ It was ‘time for justice to take a hand’ in bringing him before the courts.

That same year, during a vacation in France, Kissinger was summoned by a local magistrate keen to question him about his role and involvement in Operation Condor, a network of eight Latin American military dictatorships responsible for the abductions, torture and murder of tens of thousands. He left his hotel, shielded by bodyguards and adamant he would not yield to any such request.

In the United Kingdom, a stillborn effort was made by human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell in April 2002 to seek a warrant for Kissinger’s arrest, citing the Geneva Conventions Act 1957. The charges asserted that ‘while he was national security adviser to the US president 1969-1975 and US Secretary of State 1973-1977, [Kissinger] commissioned, aided and abetted and procured war crimes in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia’.

The presiding District Judge Nicholas Evans, of the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, conceded he could do little in the absence of the Attorney-General’s consent. Kissinger was left untouched and unruffled, which he, as a centenarian, remains.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University.

Main image: President Richard Nixon with United States National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, circa 1972. (Frederic Lewis/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)