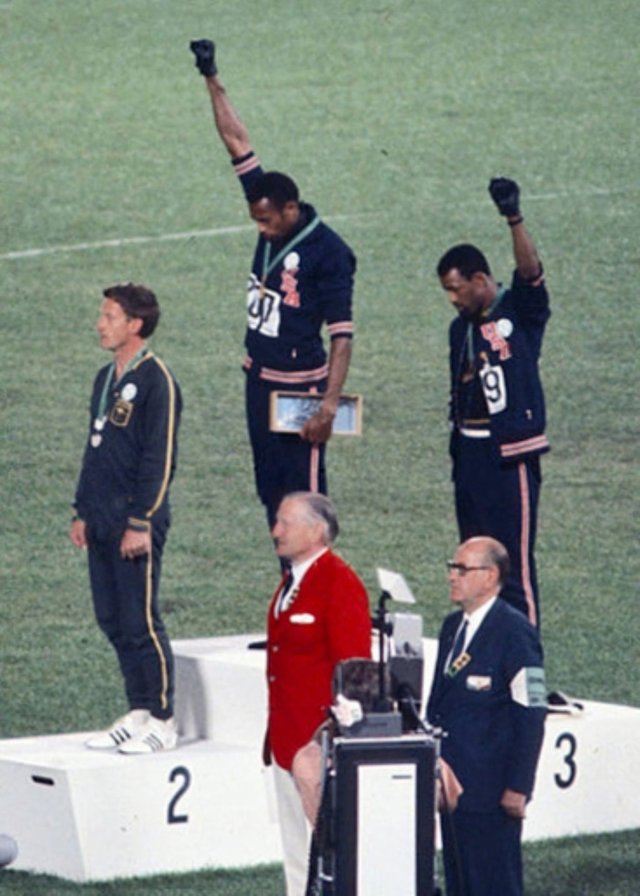

On 16 October 1968, an Australian named Peter Norman ran the race of his life to win a silver medal in the Mexico Olympics 200-metre sprint, with an Australian record time of 20.06 seconds. The presentation that followed, with US competitors gold medallist Tommie Smith (19.83 seconds) and bronze medallist John Carlos (20.10s), ended with the iconic spectacle of the Americans’ Black Power salute. Norman’s position during the Americans’ plan to protest injustice was encompassed in his calm response, ‘I will stand with you’.

As Andrew Webster noted in a Sydney Morning Herald article, ‘Time magazine considers it the most iconic photograph ever taken: the two black sprinters raising a fist, both sheathed in black gloves, into the thin Mexico City air as the American national anthem was played’.

Norman was sporting an Olympic Project for Human Rights button to protest racism, in solidarity with Smith and Carlos; it was Norman’s suggestion to his sprinting rivals that they each wear one of the only pair of gloves they had for their protest. The stadium went quiet as the anthem petered out. For the three men standing on the dais, acutely aware of the possibility of getting shot, the noise was still to come. The feedback still rumbles along, subterranean yet audible.

The fallout for Smith and Carlos was fairly public and instant; they were sent home in disgrace to eventually emerge, rightly, as heroes of the civil rights movement. As for Norman? The Australian coach slapped him on the wrist and told him, ‘You probably shouldn’t have worn that’ (the civil rights badge).

From the heights of his achievement and his participation in the protest, Norman was to become the forgotten man of Australian sport. He was dropped from the 1972 Munich Olympic Games even though he’d run qualifying times. (The five-time national 200-metre champion never represented Australia at the Olympics again.) He was ridiculed and taunted by some of his competitors back in Australia for his stance against racism. (Norman had always had Aboriginal and Chinese mates.) He was left out of a public role with his fellow greats at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

Norman’s crime? As he said at the time, ‘I believe that every man is born equal and should be treated that way’.

In his nephew Matt Norman’s documentary Salute, Norman said that he just ‘couldn’t see why a black man couldn’t drink the same water from a water fountain, take the same bus or go to the same school as a white man’. Norman believed, because of his support of the Black Power salute, that he had blotted his copybook with the International and Australian Olympic committees.

'The saddest aspect of this tale is that, for many Australians, the name Peter Norman remains unknown. His decision to stand for social justice is better known in the country of his competitors.'

Carlos and Smith shared that belief. ‘Peter was a lone soldier. He consciously chose to be a sacrificial lamb in the name of human rights. There’s no one more than him that Australia should honour, recognise and appreciate,’ Carlos had said.

‘He paid the price with his choice,’ Smith agreed. ‘It wasn’t just a simple gesture to help us, it was his fight. He was a white man, a white Australian man among two men of colour, standing up in the moment of victory, all in the name of the same thing.’

Smith and Carlos recalled how they had approached Norman after the race. They asked him if he believed in human rights and if he believed in God. Norman, a Salvationist, answered 'yes' to both questions and joined the protest.

Norman was a charismatic, conflicted individual whose personal life and sporting life were traumatised by the world’s responses. He later experienced serious sporting injuries and consequent substance addiction. As yet-unpublished interviews with family members reveal that Peter was a cheeky, larger-than-life character. A smartarse who loved people; who was at peace on that dais in Mexico. He was a man fully supportive of his fellow athletes, aware of social injustice from his own life experience and from his observation of life in the United States and in Mexico where they were competing.

Norman knew exactly what he’d done, in the moment, and why he’d done it; but he hadn’t anticipated the price. Informally reprimanded in Mexico, Norman shrugged off the flack only to come home to a polarised response. As well as adulation, he faced abuse, anger and contempt.

His family says he wouldn’t have had a second thought about it in the change room — it was the right thing to do. The vibe back home, however, was negative; the limelight had an impact; he became public property and was in some ways devoured by the media. Family members relate that Peter told them that selectors had it in for him.

Peter George Norman died 18 years ago this month (3 October 2006) of a heart attack. He was 64. His lifelong friends and brothers in controversy, Carlos and Smith, were pallbearers at his Melbourne funeral. Belated recognition of Norman’s sporting achievements and his championing of equality has trickled through in Australian awareness and social recognition. Six years after his death, on 11 October 2012, parliament passed Dr Andrew Leigh’s ‘motion of apology to Peter Norman (with no dissenting voices)’.

The motion recognised Norman’s ‘extraordinary athletic achievements’, his ‘bravery [for] donning an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on the podium, in solidarity with African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who gave the “black power” salute’, and apologised ‘for the treatment he received upon his return to Australia, and the failure to fully recognise his inspirational role before his untimely death in 2006’. It also acknowledged ‘the powerful role that Peter Norman played in furthering racial equality’.

More followed, little by little.

The Australian Olympic Committee posthumously awarded Norman the Order of Merit. In October 2019, Athletics Australia and the Victorian Government unveiled a bronze statue outside Lakeside Stadium in Melbourne, and adopted 9 October as ‘Peter Norman Day’ (following the initiative adopted in the US since Norman’s death).

The saddest aspect of this tale is that, for many Australians, the name Peter Norman remains unknown. His decision to stand for social justice is better known in the country of his competitors.

Barry Gittins is a Melbourne writer.

Main image: Wikimedia Commons