When I saw the title of Greg Sheridan’s Easter article in the Weekend Australian I confess that I was tempted to pass it by. When the West and Christianity are linked in public discussion Christianity is often reduced to its political dimensions and the West to a homogeneous mass. The conversation then descends to a binary conflict between abstractions.

I admire Sheridan, however, for his exploration and commendation of Christian faith in the public sphere. On reading his article I found that the title did not do it justice. Sheridan’s exposition of Christian faith, particularly in Jesus’ Resurrection, was exploratory and well informed, and he emphasised how countercultural it is to base one’s view of the world on belief in the Resurrection of Jesus from the dead. His article avoided polemics, recognised the importance of social justice as well as orthodoxy in Christian faith and came to a very personal and moving conclusion in describing with great affection his sister’s painful terminal illness and death. He quotes at length from the long letter sent by a pastorally gifted priest who attended her in her dying and the importance of her receiving the Sacraments for the sick. Her long illness and the peace that she found in dying echoed Sheridan’s focus on Jesus’ death and rising.

I admire Sheridan, however, for his exploration and commendation of Christian faith in the public sphere. On reading his article I found that the title did not do it justice. Sheridan’s exposition of Christian faith, particularly in Jesus’ Resurrection, was exploratory and well informed, and he emphasised how countercultural it is to base one’s view of the world on belief in the Resurrection of Jesus from the dead. His article avoided polemics, recognised the importance of social justice as well as orthodoxy in Christian faith and came to a very personal and moving conclusion in describing with great affection his sister’s painful terminal illness and death. He quotes at length from the long letter sent by a pastorally gifted priest who attended her in her dying and the importance of her receiving the Sacraments for the sick. Her long illness and the peace that she found in dying echoed Sheridan’s focus on Jesus’ death and rising.

Sheridan claims that to preach the message that Christ rose physically from the dead after being executed has a better chance of winning people than a more accommodating version of faith. In this he echoes Tertullian, the contrarian late second century Christian rhetorician.

The Son of God was crucified: that does not cause shame, because it is shameful.

And the Son of God died: that is totally credible, because it is absurd.

And after being buried he rose again: that is certain, because it is impossible.

Sheridan echoes Tertullian’s spirit, if not his verbal excess:

Christianity is a supernatural religion, with vast spiritual and eternal claims. Everything about it is radical and a bit wild. Christianity is a faith that offers comfort and acceptance, but it is also a faith of repentance, commitment, life change, prayer and forgiveness, and the unnatural practice of putting others first. It provides space for all the passionate heroism, meaning and destiny. It is bold, not bland.

At the heart of this wildness is the grounding of Christian faith in a man who was the Son of God, crucified for sedition and blasphemy but who rose from the dead to ground believers’ hope in life with God after death and their companionship with Christ in selfless living. That faith has been and remains confronting to any culture and society. If it is especially challenging to the contemporary West, that is due to the widespread assumption that there is no reality beyond the empirically verifiable, with the result that any belief in God or in a man who rises from the dead is incoherent. The relationship between Christian faith and the West cannot be parsed by associating the spirit of the West with true Christianity. The overriding primacy given to economic settings and to individual choice flow out of the reduction of reality to what can be seen, touched and counted.

Sheridan’s evocation of the wildness of Christian faith also makes it unlikely that the apparent incredibility of the Easter story alone will win people to the persons and churches that proclaim it. It may form an attractive kind of faith but not one that will be popular. To be persuaded, observers will need to see something attractive in the life of people who believe the story and belong to the churches. Not only the belief but the adventurous and generous life that embody it must be wild and attractive. This is the theme of many stories of the early Church that emphasise the courage, generosity and prayer of Christians. They honoured especially the courage with which the martyrs followed Jesus in enduring dehumanising deaths. These stories of small, brave communities joined by faith and love and attention to the needs of the local people, formed an attractive picture.

As the churches grew, however, Christians had to come to terms with the faults as well as with the virtues of their members. In the systematic persecutions of the late third century many people, including clergy, sacrificed to the Roman gods to escape torture and death. When the church was legalised it had to decide how to treat those who had betrayed Christ and to accept people with dubious motives for joining. After an acrimonious debate it opted for generosity over purity, allowing St Augustine to describe the church as a school for sinners. Christ calls people and over time forms them into disciples. In this story the Church is distinguished by forgiveness.

That tension between the high ideals of the Church of Jesus’ followers and the everyday reality of failure, forgiveness and generosity recalls Groucho Marx’s quip about not wanting to join any club that would accept him as a member. To commend Christ risen can be done only through a community of faith. But in its life that community will often hide the face of Christ.

Christians and their communities are always caught between faith and doubt. Not only observers but Christians themselves need to find the wild and the surprising face of Christ in one another’s life. Greg Sheridan’s story of his sister’s last days, told with love and acceptance, points to that deeper reality.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

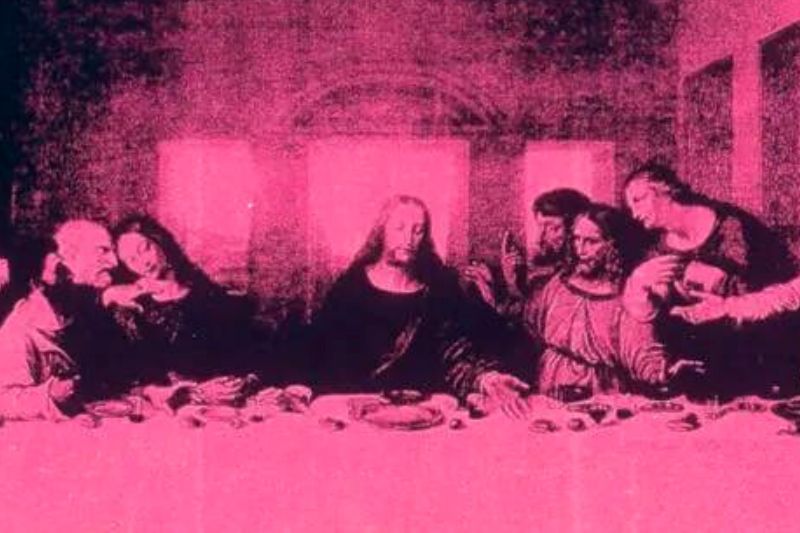

Main image: Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (detail), 1986, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.