The usual method for dividing up the world economy is to distinguish between developed countries and developing countries: the rich world and the poor world. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the divisions were slightly more complex: First World, Second World and Third World. The Second World was the communist countries, principally China and Russia.

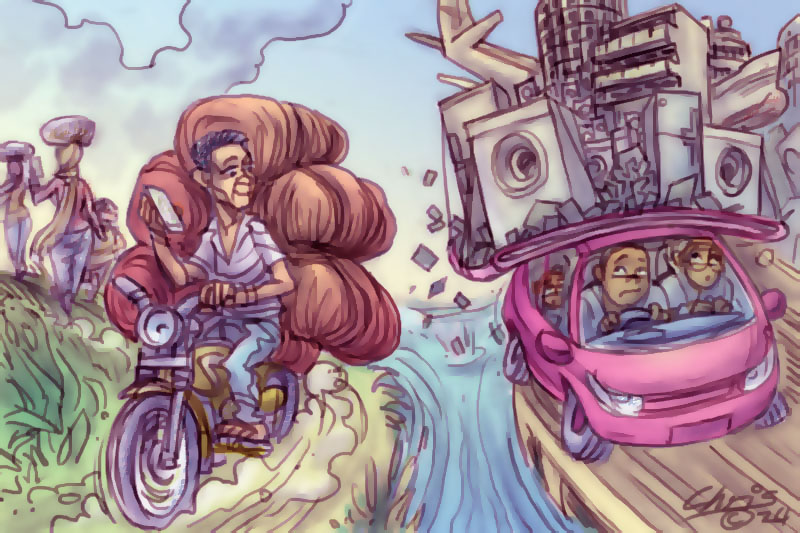

What is starting to emerge is that the future of much of the developed world is looking bleak, while the developing world arguably has better prospects. That does not mean that the wealth gap is about to disappear, but it does mean that there is very likely to be a narrowing.

The reason is that advanced industrial societies are running out of ideas. They have been able to keep the illusion of advancement going in the last few decades, mainly through the use of financial trickery, but that, too, is faltering. Meanwhile, the developing world can start to move through the industrial phases. For these countries, what they have to do to improve the lives of their people is clear, especially with infrastructure. It is far from clear for developed nations.

The signs of decline in the developed world are many. The business analyst and music critic Ted Gioia estimates that about a decade ago technology stopped contributing to human flourishing. He writes that the largest tech investments have gone into creating fantasy and unreality. ‘Trillions are spent on virtual reality and artificial intelligence’ resulting in intense fakery and lying in the public sphere. ‘Real people become inputs in a profit-maximization scheme which requires that they are constantly controlled and manipulated ... in this environment, everything gets viewed as a resource or input and the natural world (including us) is ruthlessly exploited.’

Gioia calls it a ‘parasite culture’ noting that companies like Facebook, Google, Spotify and Tik Tok create nothing, they only profit from the creation of others.

Another sign of decline is dramatically falling fertility rates, which inhibits growth because it leads to falling populations and weakening demand. The total fertility rate in the OECD, the developed countries, dropped from 3.3 children per woman in 1960 to just 1.5 children per woman in 2022, far below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman. Developing countries have much higher fertility rates.

Capital in modern ‘capitalist’ societies no longer principally funds productive activities, especially tangible ones, because there is insufficient profit in it.

Perversely, developed countries have been a victim of their own success. Decades of relentless efficiency improvements in primary and secondary industry have meant that people’s most basic needs, such as food and clothing, are easily satisfied. The situation is more complex with shelter (housing) and energy, but for the most part what obsessed older societies, and still does in many developing nations – having an economic system that keeps people alive – has long since been solved.

This can be seen in the relative importance of industry sectors in the world economy. Less than 5 per cent is devoted to agriculture, just over a quarter is accounted for by industry, of which 16 per cent is manufacturing, and almost two thirds is in the services sector. That is what the post-industrial world looks like. Many of the basics of life are satisfied and the emphasis shifts to less essential activities.

The problem is that because capitalism requires endless growth, a continual increase in the value of transactions, it is not possible to stop, or slow down, when fundamental needs have been satisfied. Consequently, many things that were outside the transactional system were monetised to create the fiction that progress was continuing. Consider, for example, sport. It was once almost entirely amateur, a leisure activity. Now, it is big business, part of the ‘services sector’. The monetisation of human attention, called the attention economy, is an another example of the effort to find new ways of generating transactions, to keep ‘growth’ going.

This century, the main way the growth challenge has been met is through financialisation: the making of money out of money, as can be seen in Australia’s bloated property prices. As the finance journalist John Lanchester comments, modern finance does not in itself produce anything, nor does it mainly focus on funding productive activity. ‘What modern finance does, for the most part, is gamble,’ he writes. ‘It speculates on the movements of prices and makes bets on their direction.’

Thus capital in modern ‘capitalist’ societies no longer principally funds productive activities, especially tangible ones, because there is insufficient profit in it. Almost everyone has a fridge and a washing machine, they are cheap, so why invest in the white goods sector? And then there is the problem of too much stuff. Before the Covid crisis muddied the waters and disrupted supply chains, in many industry sectors there was chronic oversupply, meaning low profitability.

That oversupply, which is a result of the combination of improved efficiency and weak demand, is still there and it poses a threat to developed economies, especially as they are coming to the end of their ability to create ‘growth’ by piling on debt. The unanswered question is: ‘If the capitalist treadmill can never end, what will keep it going? Metaworlds and fake universes generated by AI?’

In the developing world, by contrast, there is a clear direction: emulating what developed nations have done. That is what China did when transforming itself from a Second World nation to a First World nation. It simply copied the West, and, because it had the benefit of the West’s accumulated knowledge and efficiency gains, did so with extraordinary speed.

Now China, too, has contracted a developed-world disease in the form of a massive overbuild in its property market, whereby it has approximately twice the dwellings it needs. Which is why China, and another former Second World nation Russia, are moving so fast with the BRICS+ alliance in what is arguably the most important financial and economic development since the Bretton Woods agreement after the Second World War that established the modern financial system.

For China in particular, using BRICS+ to improve the standard of living of developing nations is crucial because it is a way to find new customers for their manufacturing output, which they badly need to get out of their financial cul-de-sac. Hopefully, such moves may eventually turn out to be good news for the poorer people of the world.

David James is the managing editor of personalsuperinvestor.com.au. He has a PhD in English literature and is author of the musical comedy The Bard Bites Back, which is about Shakespeare's ghost.