The push to introduce Artificial Intelligence (AI) into many areas of modern life is an existential threat to the human race. Not because computers will replace human intelligence, which can never happen, but because the aim is to convince us that human intelligence does not exist. To avoid being tricked into technocratic servitude, it is vital to assert how wondrous, mysterious and polyvalent the human mind is.

AI and its offshoots, such as transhumanism, will continue to have a significant impact on the job market by automating mechanistic activities in the service sector, including in highly paid areas like law, education, journalism, graphic design, even music.

Tertiary industries that rely on deduction will be particularly affected, leading to the kind of transformation that has already occurred in primary and secondary industries, which have experienced efficiency improvements that have radically changed the living standards of the world’s population. But any job that involves interaction between self-aware humans will not be threatened because computers do not have, and never will have, consciousness or the ability to relate to people that accompanies that.

AI is self-generating software that is capable of continuously adapting by interacting with the data it receives. The deception is that this self-referential quality is the same as human awareness, which is also self-referring (‘I am aware of myself: I can see me’). Thus technocrats talk about a machine ‘learning’. To state the obvious — and the obvious needs to be continually repeated to counter this dangerous sophistry — no machine can apprehend its own existence. They are not even organic. When a human learns something, they are aware of themselves having found something out. A machine can only be created, by self-aware humans, to be a simulacrum of that.

To say, as many proponents of AI claim, that it is just a matter of increasing computational power and it will become possible to give computers a subjective, internal life is to profoundly misunderstand what a subjective internal life is. As one analyst commented, he would only be concerned about conscious machines if ‘these machines start worrying that their parts might be wearing out’. These repeated assertions by AI proponents, who see themselves as being at the vanguard of science, are actually deeply unscientific — immature thinking untroubled by empirical or philosophical rigour. Perhaps that is why they so often dress like teenagers.

Consider the logic of it. When someone, say Elon Musk, has a clever, high-IQ thought, then he will be aware of having had that clever, high-IQ thought. So who is watching that thought? It is Elon Musk’s consciousness, or core being. Can a machine, made up of inert components, ever watch its own workings? What with?

That is only the start of the problems. The mind is experienced by us as a single thing. The philosopher Descartes said: ‘I am only a thinking thing; I cannot distinguish in myself any parts. Our minds have a unity.’ The mind has no components, whereas computers consist of nothing but components. Moreover, those components mostly operate serially, one function after another. The human brain tends to operate with parallel networks, everything at once. The two are not interchangeable.

'AI and transhumanism will continue to transform economic life on the planet. Rather than trying to stop it, which will fail, the counterattack should instead be to repeatedly insist on the obvious: that the ‘I’ in AI is not human intelligence, and that the ‘humanism’ in transhumanism is not human.'

Another issue is that humans can think effectively with loose or incomplete information. The computer scientist John von Neumann noted that the human nervous system is very imprecise, and ‘no known computing machine can operate reliably and significantly on such a low precision level’. Yet humans can form ideas from vague or imprecise elements; that is largely what intuitive or inductive reasoning is. With computers it is always a case of rubbish in, rubbish out, which is worth remembering when computer modelling is preferred to good sense.

Another problem is that maths, from which computer algorithms are derived, cannot model consciousness because it is an infinite regress: ‘I am aware/I am aware of being aware/I am aware of being aware of being aware’ and so on. To quote Hamlet, we are ‘infinite in faculty’.

As the historian of science Stanley Jaki noted, a ‘conscious man is a unity in which the potentially infinite sequence of acts of self-reflection do not signify distinct parts of a thinking apparatus … Consciousness is the perceiving field of qualitative differences as opposed to the quantitative structure of external things. Consciousness is also the matrix of experiences about the self, about the purpose in action, and about the meaningfulness of judgments … only man can abstract and rise to the level of universal concepts.’

Of most concern are the moral implications. Morality depends on having a conscience, self-awareness. To believe that AI can replace human thinking is to take the ability to distinguish between good and evil off the table. Coding ethical precepts into computer algorithms is not a substitute. It is like saying that the 10 commandments are really a still-alive Moses instructing us on how to make moral decisions.

Physicalists, who believe that humans are nothing but matter, and that the mind and the brain are the same thing, face unsolvable problems when it comes to AI. Human brains each day lose about 85,000 cells or neurons. Computers will not work if a single part is lost. With computers, size equates with capacity. Analyses of the brains of geniuses shows no correlation with size. These physical differences between computers and people do not augur well for attempts to create a computer/brain interface (such as Musk’s Neuralink).

AI and transhumanism will continue to transform economic life on the planet. Rather than trying to stop it, which will fail, the counterattack should instead be to repeatedly insist on the obvious: that the ‘I’ in AI is not human intelligence, and that the ‘humanism’ in transhumanism is not human. These aberrant ideas have a long history: similar claims were prosecuted 700 years ago by Raymundus Lullus in his Ars Magna. But opposing them has become crucial. It is not just a matter of logic or clear thinking; it is about defending our humanity against those who would degrade it.

The ultimate irony is that because our minds are so remarkable we are able to imagine impossible, science-fiction notions like AI and self-conscious cyborgs. But it is essential to remember that it is all fiction. Jaki writes: ‘The crucial issue in the man-machine relationship lies not in what machines can do but in the concepts that man forms about machines and about himself. As long as this is done with proper concern for man's uniqueness, there is no cause for alarm.’

David James is the managing editor of personalsuperinvestor.com.au. He has a PhD in English literature and is author of the musical comedy The Bard Bites Back, which is about Shakespeare's ghost.

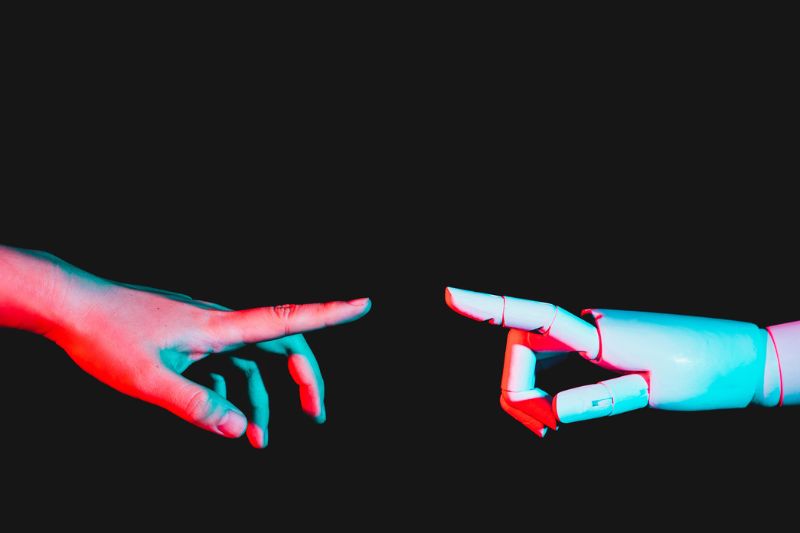

Main image: Human hand reaching for robotic hand. (Getty images)