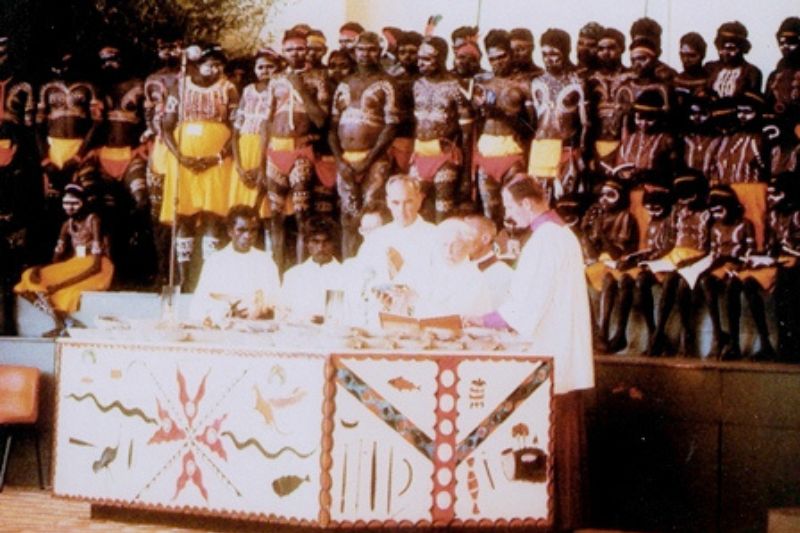

February 24 will remain in peoples’ minds and for many years to come being the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But for some of us, February 24 holds another, more sustaining and life-giving memory. It was on that day 50 years ago at 3pm on a Saturday afternoon at the Melbourne Myer Music Bowl when many of us heard a strong and joyful Aboriginal Voice for the very first time. Many voices, in fact.

The event, part of the 40th International Eucharistic Congress, was titled the Australian Aboriginal Liturgy and it involved a very large number of Aboriginal people, particularly from the Kimberley of Western Australia and Northern Territory, who had come down to participate in the event. This group numbered more than one hundred and fifty adults, teenagers and a children’s choir.

This liturgy was, for many of us who were present, the first time we had witnessed and experienced Aboriginal people expressing their Catholic faith in ways that were culturally different from our own but very significant to them. The ancient Catholic liturgy took on a new dimension of life and energy as people sang in their own language, mimed the Word of the Gospel and danced.

This first public and national Aboriginal Liturgy was highly significant. It was the first attempt by the Catholic Church in Australia to re-shape the ancient Catholic ritual of the Mass, which itself had already changed and adapted in the light of Vatican II in the late 1960s. In this case, the attempt was in the light of the faith experiences by those belonging to an even more ancient culture. Or, more accurately, Aboriginal cultures. It was no easy task.

The liturgy had been long in the making. It owed much to the energy and commitment of many Aboriginal people who had found encouragement in the living and cultural expressions of their Christian faith. These communities of faith were largely spread across the north of Australia and were strongly supported by various priests and religious men and women.

In the Northern Territory communities of Port Keats Mission (now Wadeye) and Bathurst Island Mission (now Wurrumiyanga) Missionaries of the Sacred Heart priests and Daughters of the Lady of the Sacred Heart sisters were particularly involved. In the Western Australian Kimberley community of La Grange Mission (now Bidyadanga) and in the town community of Kununurra, Pallottine priests and Sisters of St Joseph were also very involved.

One Pallottine priest, Kevin McKelson, who helped shape the final English version of the liturgy was living in La Grange Mission and had spent much of his life learning the local Aboriginal languages. He explored how they, along with cultural signs and symbols, might sit within a Catholic liturgy. He had first translated the English liturgy into Karajarri, a local Aboriginal language, and then back again into English to try and find appropriate expressions.

'That liturgy on a Saturday afternoon in a Melbourne summer was never intended to be the final word or assume the final shape of a more culturally sensitive and inclusive liturgy. It was only a beginning.'

The task required to shape this new liturgical ritual was enormous and it required a deep listening, respect, and attentiveness by those involved encouraged by other efforts at successful cultural inculturation in the Church’s history. It also needed approval from Rome before it could be celebrated. Drafting this new liturgy took shape in Darwin, May 1972. Approval of a final version came through from Rome in November that same year.

Those who had prepared that first draft had been trying to listen to ‘cultural patterns, thought patterns and social structures’ of the various Aboriginal communities in the north of Australia, ones that the Church was in contact with at that time. The process explored various signs and symbols, acknowledging that this was a complex area with much variety amongst different worshipping communities. And, while the final version was in English, it sought to express a pattern of language expression that would be accepted by many groups where the handing on of an oral tradition was often expressed by word, dance and repetitive chants, accompanied by hand clapping, clapsticks or didgeridoo. The music of Daniel Puatjimi (Wirrumiyanga), a Tiwi canoe tune, was also used to accompany some of the text.

This new liturgical expression sought to acknowledge that Aboriginal people had lived within a context and consciousness of the transcendent for generations. Religious experience was part of the fabric of their daily lives and the ceremonies they regularly conducted. They knew what it was to have faith in the power and sacramental nature of symbols. They were open and enthusiastic in exploring new ways to express and share their Christian faith.

Since 1973, only the Broome Diocese has attempted to find a formal expression of a more appropriate Catholic and Aboriginal and Torres Strait liturgy. The Missa Terra Spiritus Sancti, Mass of the Land of the Holy Spirit (2018) may be celebrated in the Diocese of Broome and in other communities only with permission from the Bishop of Broome and the local bishop and, while it is in English, it has also been translated into Aboriginal languages.

Thirteen years after this celebration Pope John Paul II would visit Central Australia. He is often well remembered for the many encouraging things he said that day. But one that is often quoted continues to remain both an invitation and on-going challenge for the Australian Church: ‘the Church herself in Australia will not be fully the Church that Jesus wants her to be until you have made your contribution to her life and until that contribution has been joyfully received by others’.

Perhaps this February 24 we might ask of ourselves, both the Aboriginal peoples and those of us descendants of those who sought a home in this land: ‘What is the contribution that First Nations people have offered to our journey of life and Christian faith and how has it been received?’ Some of our parishes acknowledge the land they pray on as they begin their weekly services and pay respect to those who have held a sacred and custodial relationship with the land over thousands of years. Sometimes, smoking ceremonies have opened meetings, conferences, funerals or gatherings, offered in the context of healing and inner cleansing. Aboriginal Christian art exists in many forms and can be seen in liturgical vestments and on our church and home walls.

In addition, ever revealing and refreshing, are the various Stations of the Cross presented by Aboriginal artists such as John Dunn, Richard Campbell, Miriam Rose Ungunmerr-Bauman and Matthew Gill. All very distinctive and striking, offering fresh theological and spiritual insights. They are a reminder that where some Aboriginal people most identify with the Christian story is the journey of Jesus to his crucifixion.

Hence, it is not surprising that it is in this religious context of cultural ‘sorry business’, the gathering, lamentations and rituals around those who die, that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the nation continue to express cultural values. Whether it be in north or remote Australia, the Torres Strait or in mainland towns and cities the celebration of funerals continues to convey people’s resilience, kinship and spirituality. These rituals may vary considerably across the nation but within their expressions they also hold a historical memory of pain, loss and grief.

In terms of the life we share as Australians, it is possible that one of the greatest gifts the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to give to the Christian community is how they understand their sacred and ancient connection to the land. This relationship, founded on living in harmony with creation, is not one about control, domination or ‘ownership’ but being open to encounter the sacred. And being led, nurtured and taught by the sacred in return.

This relationship speaks to a depth of care and listening to the land, so strongly endorsed by Pope Francis in Laudato Si’ when describing how Indigenous people throughout the world encounter their ancestral spaces: ‘For them, land is not a commodity but rather a gift from God and from their ancestors who rest there, a sacred space with which they need to interact if they are to maintain their identity and values’. (#146).

The growing awareness by many Australians of the implications of climate change offers a new space to encounter the sacred in this land. It speaks to the vulnerability that we, and our land, now share and the many plant and animal species that face extinction. It offers an opportunity for Aboriginal people to help other Australians listen to the land they walk upon and learn to respect it as gift and sacrament. It offers a space where the human and the sacred can meet, as they have for thousands of years, but in new, humbling and enriching ways.

Fifty years ago, a large group of Aboriginal people presented something new to the world and the Catholic Church. It opened hearts and minds as it revealed how Christian faith was a living, relational and dynamic experience, always in the process of being invited into new depths and awareness of the sacred. Our Australian Church owes much to those early pioneers of inculturation, particularly those Aboriginal song and dance composers, artists and language translators.

It would be a great shame for the Catholic Church in Australia if it failed to keep listening to that voice of the Holy Spirit in this very ancient land. That voice, coming from the lived experience of Aboriginal people, can further enrich our Christian faith but also reveal how we might seek to better live and walk, carefully and respectfully together upon the land.

That liturgy on a Saturday afternoon in a Melbourne summer was never intended to be the final word or assume the final shape of a more culturally sensitive and inclusive liturgy. It was only a beginning.

Brian F. McCoy SJ is the former Provincial Superior for the Australian Province of the Society of Jesus (2014-2020). He completed a doctorate in Aboriginal men’s health at the University of Melbourne, later published as Holding Men: Kanyirninpa and the health of Aboriginal men. He has spent half his adult life in a various Aboriginal communities in north Australia. As a young Jesuit scholastic, he was involved in the responsibility of hosting more than three hundred Aboriginal people who had gathered from all around Australia during the Eucharistic Congress. There was a core group of four coordinators: Fr Hilton Deakin (later, Assistant Bishop of the Melbourne Archdiocese, dec. 2022); Fr Brian Morrison SSS (dec); Pat Dodson (then a MSC seminarian and now a Federal Senator); and Brian McCoy SJ.

Main image: The Australian Aboriginal Liturgy (MDHC Archdiocese of Melbourne).