For those of us born in the 20th and 21st centuries, movies are inherent to daily life. We automatically suspend our disbelief, buying into the premise of the plot so as to be transported without delay into other realms. For more serious viewing with documentaries and educational filmmaking, we can quickly choose to engage in the filmmakers’ efforts, accepting or rejecting their premise without any great cognitive efforts. We are accustomed to film. Be it on the big screen, on YouTube, TVs, laptops or phones. For generations, film as a visual medium has been there to tell our tales, relate our news and frame out ‘truths’. Yet it has not always been thus.

In a little-known origin to the film industry pre-Disney, Barbie and Marvel, many of its techniques and stratagems were pioneered Down Under in the colonies. Call it an historic accident or a bit of divine serendipity, for 18 years (from 1891-1909) a Christian enterprise called the Limelight Department became one of the world’s first film studios, operated by The Salvation Army. They produced more than 300 movies right here in Melbourne, Australia.

Some of the strangest cultural achievements in Australia’s post-European settlement history revolve around these Salvo flicks. The world’s first multimedia extravaganza incorporating film was Soldiers of the Cross, produced in 1900. It contained 15 sections of film consisting of 90 seconds each with an additional 200 lantern slides. This narrative drama on film was filmed around Melbourne and viewed by 4000 people in Melbourne’s Town Hall in 1900. Long before Cecil B. DeMille, the Salvos’ bloodthirsty account of Christian martyrs being chopped up and gobbled in Rome’s beastly gladiatorial arenas had filmgoers gasping, with some of them allegedly fainting in the aisles.

There was also the new federal government’s issuing of a contract to capture Australia’s ‘birth’ through with the world’s first film documentary, with the federation events in 1901 in Sydney and Melbourne. The Salvos used mounted platforms to shoot the world’s first film doco, which featured the first use of multi-camera coverage. It was the most widely distributed Australian film of its time (predating the world’s first feature-length narrative film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, which opened in Melbourne on Boxing Day, 1906).

The Salvos poured money into their filmmaking enterprise and received cash from ready punters in Australia and New Zealand, who were keen to see and hear moving images and recorded music; often for the first time in their lives. There were 20 Salvo ‘Biorama’ teams touring Australasia to stage the shows, complete with brass bands and orchestras, and the Salvo cinematographers referred to themselves as showmen.

For the Salvo auteurs, there were also lucrative government contracts to be bid for and won. Filmmaking for the Salvation Army in its halcyon days was a win-win – they were able to share their peculiar message of redemption from sin, misery and poverty; to recruit new members to the cause, and raise funds to pay for their social work.

Lovers of alternate history may dream of what may have been for Australia, had it remained the international Mecca of movie culture and mass media it was in those pre-Hollywood days (the first Los Angeles film studio opened in 1911). For a brief, sunny reign, Australians stood unchallenged at the pinnacle of filmmaking and filmgoing.

'For a brief, sunny reign, Australians stood unchallenged at the pinnacle of filmmaking and filmgoing.'

Why, you may ask, did that state of affairs not continue? The usual historical suspects raise their heads: money, (family) politics, and sex. The Salvos’ luck ran out when it came to landing government contracts, which impacted a bottom line weighed down with the costs of production and touring companies. The dour Scot who killed the film-making fun, James Hay, observed that making movies had ‘affected at the time many aspects’ of the Salvation Army’s finances, but within two years of closing the Limelight Department ‘the income of every department was greater than ever’.

Hay was a protégé of Bramwell Booth, who was the Army’s second-in-command back in London, and Bramwell had won a family spat with younger brother Herbert, a gifted songwriter and screenwriter who was running the show for the Salvos in Australasia. Herbert had built up the movie production as well as writing the scripts and taking a lead role in narrating (the ‘talkies’ were still years away from being produced, the first produced in Hollywood in 1928).

Bramwell was a centralist who insisted on obedience, whereas Herbert wanted to call the shots Down Under. The brothers fell out and Herbert resigned from the Salvation Army, ceding his copyright to more than 180 songs and buying Soldiers of the Cross, which he literally showed around the world until it disintegrated and he passed away, in 1926. It got messy – Herbert Booth’s name was chiseled off the foundation stones of some Salvation Army buildings. When Herbert Booth was buried in Valhalla, New York, his gravestone was intentionally facing the opposite direction, away from the Salvation Army section as one last protest at the treatment he received.

Sex was the main sticking point, the record suggests. Things were livening up on film, and people were shown – Heaven forbid! – embracing and kissing. At the time, a form of Puritanism reigned, and the Salvos retreated from the movie business. ‘It should be noted,’ Hay wrote, ‘that the cinema, as conducted by The Army, has led to weakness and a lightness incompatible with true Salvationism, and was completely ended by me… It may be argued that the still or motion picture would make great impressions. Alas for that hope! Money-makers from the showmen of the entertaining world swept this off its moral base, and now [cinema] is the habitation of all manner of unclean things.’

.png)

In an ironic grace note to the script, in his retirement Hay wrote that he loved to mill around movie lovers, attaching himself ‘to queues and cinemas’ in a hope to proselytise and ‘lead people’s thoughts to higher planes’. If Hay had seen the potential of film to lift people’s spirits and inspire them, to entertain and challenge, he could have attempted to convert millions happily chewing popcorn and rolling Jaffas down the aisles as they watched Salvo movies.

The world premiere of Limelight was on Wednesday, 21 August 2024 in Melbourne, at the Palms, Crown.

Barry Gittins is a Melbourne writer.

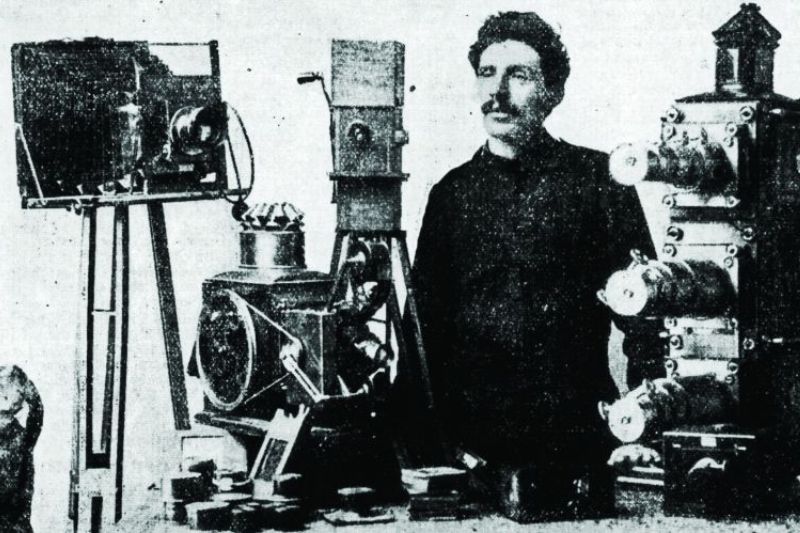

Main image: Captain Joseph Perry of The Salvation Army’s Limelight film studio. (Courtesy of the Salvation Army)