Back in his Beatle days, Paul McCartney had a way of dealing with ever-changing time zones: he would wear a second wristwatch. Six decades on, the man is still crisscrossing time zones, taking on the world one concert at a time. However, traversing decades as well as time zones requires a little more than just a spare watch.

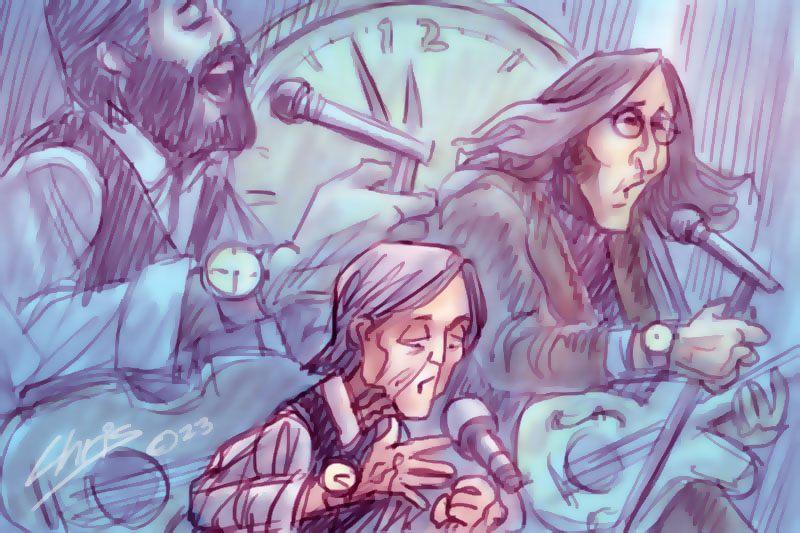

With the Got Back tour now playing across Australia, McCartney’s embracing more than just the spirit of his past: he’s woven cutting-edge tech into the fabric of his performance. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the transcendent ‘I’ve Got a Feeling’, pairing Sir Paul with the projected voice and presence of John Lennon. And it feels like more than a performance; it’s a poignant rendezvous across time.

In a recent interview with the ABC’s Sarah Ferguson, Sir Paul quipped, ‘We really are singing together, even though it’s with technology’. It’s a kind of time travel that sees Lennon performing on a London rooftop in 1969 while McCartney accompanies him from a stage in 2023. The result is a blend of nostalgia and innovation, served with a side of audio-visual perfection.

Arguably though, McCartney long ago learnt how to traverse decades at dizzying speed. The Beatles’ meteoric rise wasn’t just fast, it altered the very framework of how we measure artistic ascendancy. A body of work complex and diverse enough to have been produced across a lifetime was compressed into a few short years.

While most young people don’t give retirement a second thought, McCartney wrote ‘When I’m sixty-four’ when still in his mid-twenties. The speed at which his life was travelling must have made imagining a time ‘many years from now’ second nature.

That once-imagined future has now arrived. It’s in the technology that resurrects John Lennon to harmonize beside McCartney, no matter where he sets his stage. Lennon’s absence in the physical realm doesn’t eclipse the powerful, enduring synergy between the two. Their harmonies might spring from different eras, but the resonance remains intact.

'Those who trade in magic usually go to great lengths to assure audiences that there is nothing up their sleeves. With McCartney, this is not merely rhetoric. ‘I love it,’ McCartney said, speaking with the audience. ‘That’s all there is to it. I love music.'

For audiences, the union of Lennon and McCartney onstage again is nothing short of alchemy. And it’s touching to see that despite Lennon’s death over forty years ago, McCartney’s relationship with his legendary collaborator continues. Not that surprising, perhaps, since those we are close to in life never really disappear.

But while audiences are afforded a surreal glimpse of Lennon and McCartney together, McCartney’s main concern remains the performance itself. In that sense, things haven’t changed much since their earliest gigs at the Cavern Club. His relationship with music retains an earnest freshness; a purity, and he is happy to concede that he is no closer to divining the source of music’s power: ‘If you try and analyse it, it’s just a bunch of frequencies . . . I don’t know, it’s magical’.

The same might be said of the tech that enables McCartney to duet with Lennon: as wondrous as it might be, stripping it down to its bare mechanics hardly does it justice. McCartney’s point is incontrovertible: art cannot be reduced to the technology that is used to create it.

As evidence, watch the deepfake Beatle in the video for ‘Find my Way’, a recent McCartney track remixed in collaboration with Beck. Or consider the even more unlikely ‘final Beatles record’ slated for release later this year. Featuring a past vocal performance by Lennon and augmented by contributions from McCartney and Ringo Starr, the track uses AI to isolate Lennon’s voice from background disturbances on the source tape. ‘Can’t say too much at this stage but to be clear, nothing has been artificially or synthetically created,’ McCartney wrote on X. ‘It’s all real and we all play on it. We cleaned up some existing recordings — a process which has gone on for years.’

By singing with Lennon again, McCartney once again finds a new way to challenge the preconceptions of concert-goers. And this is no small feat, for an audience that has known his music all their life. As I say, when Lennon appears, it somehow feels like more than just a duet. What audiences are witnessing is McCartney making a connection with an era we’re still loath to leave behind.

The cliché that Paul McCartney represents ‘living history’ is perhaps trite but not entirely misplaced. And given ours is a cultural moment often maligned for its fragmentation, McCartney’s generation-spanning appeal may provide a sense of unity and continuity that is especially needed.

McCartney himself has discussed the communal magic of performing a song that everyone immediately recognises: all the phones go on and the arena ‘lights up like a galaxy’. This is what shared cultural memory looks like, across decades and across generations.

It’s not surprising that reviews of his shows can, at times, become more an emotional testament than a critique. Sometimes his shows seem to have more in common with transcendental religious experiences than entertainment, as last Saturday night's concert in Melbourne proved (try singing along to 'Hey Jude' with Paul McCartney and 50,000 other people without tearing up). Sometimes all a reviewer can do is to offer a single evocative word: ‘magical’.

Those who trade in magic usually go to great lengths to assure audiences that there is nothing up their sleeves. With McCartney, this is not merely rhetoric. ‘I love it,’ McCartney said, speaking with fans in an intimate Q&A session during soundcheck in Adelaide. ‘That’s all there is to it. I love music.’

Instead of fighting the relentless march of time, the legendary musician continues to embrace its different beats. And while he may have left behind the second wristwatch years ago, McCartney has masterfully synchronized the heartbeat of generations. Because for Sir Paul, it’s never been about measuring moments but making them timeless.

David Rowland is a Melbourne teacher with a doctorate in English Renaissance drama.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.