Anna Funder’s recent book, Wifedom, is a sustained indictment of patriarchy both in particular and in general. Firstly, and very specifically in particular, it is a searing indictment of George Orwell’s treatment of his wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, during the nine years of their marriage.

Secondly, and also in particular, it is an indictment of the six classical biographers of Orwell in that they are complicit with him in obliterating the memory of O’Shaughnessy from their consideration of Orwell’s life and times.

Thirdly, and more generally, it is an indictment of the ways in which casual patriarchy and ‘wifedom’ continue to dominate male/female relations even in the most enlightened families and circumstances.

Eileen O’Shaughnessy (1905-1945) was a scholarship Oxford graduate and studying for a Master’s in Psychology at University College, London, when she met Orwell at a party in 1935. They were married a year later. She dropped out of university and lived with her husband in distressingly primitive conditions in a 17th Century country cottage. There she was his literary amanuensis, his editor and typist, his more-than-occasional nurse (Orwell suffered from tuberculosis), his live-in cook, plumber and gardener, and parent to their adopted son. She alone ran their farm and shop and even undertook part-time employment so that her husband could devote himself to his evolving literary career totally unencumbered by domestic and familial responsibilities. But, more than that. Funder suggests – and advances evidence to this effect – that O’Shaughnessy not only edited but also contributed to, and even inspired, some of his later works, especially Animal Farm (1945).

Yet nowhere in his writing does Orwell acknowledge Eileen either by name or as a strong, intelligent, resourceful woman in her own right. Nor does he seem to appreciate the support she afforded him which enabled him to devote himself so exclusively to writing and politics. She is the invisible woman in his life, not only unacknowledged, but, Funder suggests, in Orwell’s eyes not worthy of acknowledgement. It is patriarchy writ large, and all the more confronting for being so casual.

The classical biographies of Orwell share in this casual patriarchy. They, too, fail to acknowledge Eileen’s influence on Orwell and the extraordinary demands he extracted from her. Significantly, all these biographers are male, and one cannot help but think that Orwell’s casual patriarchy is a shared chromosomal blind-spot in their critical assessment of his life and times. Funder then suggests gently but, nonetheless, firmly that this casual patriarchy continues to affect most male/female relationships, even suspecting that her own marriage is not exempt from its influence.

'Perhaps the participants in the Roman Synod could profit in the three-day retreat that precedes the Synod from a reading of Wifedom and a showing of Barbie.'

Granted this more general observation, it is perhaps not altogether surprising that this same theme of patriarchy emerges as a significant dimension in a context far removed from scholarly literary studies, the recent box-office sensation, the film Barbie. There Barbie’s boyfriend, Ken, transitioning from the Barbie paradise, Barbieland, to the real world, is infected by patriarchy in an extreme form, machismo even.

Initially, in the Barbie paradise, Ken is Barbie’s male appendage, a ‘handbag’ boyfriend. In Barbieland every night is ‘girls’ night out’, and any attempt on his part to enter into a more intimate relationship with Barbe is doomed to frustration. But when he transitions with Barbie into the real world the situation is reversed. Barbie is no longer a princess as modern feminists repudiate her, but Ken comes into his own as a member of the ruling patriarchal class. Anything is possible: professor, surgeon, politician – he is male.

So, armed with this new-found status and confidence Ken returns to Barbieland and, with the assistance of like-minded males, proposes to subvert the matriarchal constitution of the Barbie paradise. Initially he is successful, but, unfortunately for him and his assistants, the form of patriarchy which he espouses rapidly degenerates into an extreme machismo. Inevitably there is internecine quarrelling and competitiveness among the males. This distracts them from their plans to delegitimize female dominance. They are led astray by clever female pandering to their pride and patriarchy. Their coup never eventuates, female order is restored, and Barbieland remains ‘girls’ night out’, purged of patriarchy.

Patriarchy masquerades in many forms in the Catholic profile, and one of the items high on the agenda of the upcoming Synod on Synodality in Rome in October is the place of women in the Church. Hierarchical male governance, clericalism, celibacy, non-inclusive liturgical language, the reservation of priesthood exclusively to males, sexuality and reproduction matters generally, all consideration of these is impregnated with patriarchy. Even Pope Francis himself, who has been quite innovative in creating opportunities for women in the Church, speaks more often of the ‘complementarity’ of men and women than of their ‘equality’.

It will require a massive re-thinking if these agenda items are to be honestly addressed in the Synod. Casual patriarchy is not confined to many male/female partnerships. Modern parables like Barbie serve as a reminder for its presence endemic in our society. Perhaps the participants in the Roman Synod could profit in the three-day retreat that precedes the Synod from a reading of Wifedom and a showing of Barbie.

Bill Uren, SJ, AO, is a Scholar-in-residence at Newman College at the University of Melbourne. A former Provincial Superior of the Australian and New Zealand Jesuits, he has lectured in moral philosophy and bioethics in universities in Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth and has served on the Australian Health Ethics Committee and many clinical and human research ethics committees in universities, hospitals and research centres.

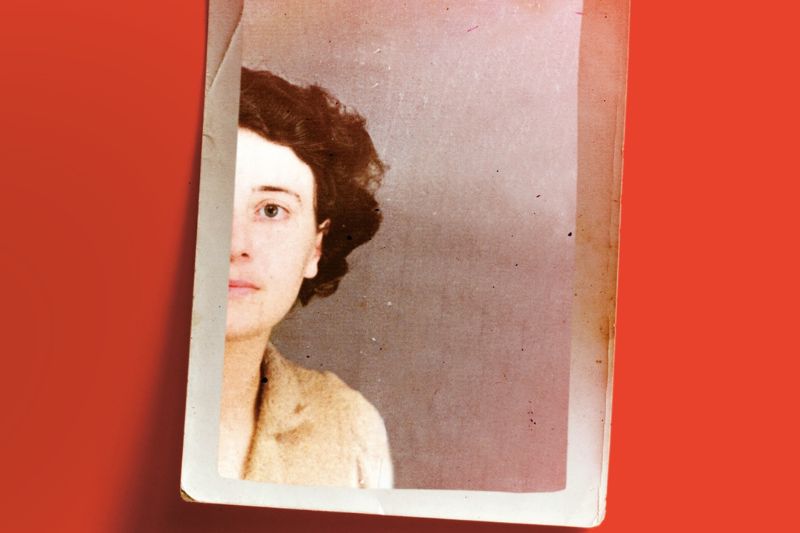

Main image: Detail from Wifedom cover (Penguin Books Australia).