It is always tempting to imagine that the discontents of our own nation are unique. To look around us and discover we are not alone is bracing. We may discover to our discomfort that our dysfunctional responses to them are also shared.

In the last fortnight, the Australian High Court declared that the indefinite detention of people whose visas were cancelled, but who could not be returned to their own nations, was illegal.

As a result, about 100 men had to be released, some of whom had been convicted and served sentences for serious crimes. In the messy aftermath the Government rushed through legislation to impose reporting to authorities, and the presumption that those released will be bound to wear ankle bands, will be subject to an all night curfew, and will be forbidden to pass close to schools and other places. Each breach of these conditions would be a criminal offense subject to a mandatory one year imprisonment. After the political demonisation of those released one can imagine what vituperation will be heaped on foreign looking people wearing an ankle bracelet. The Government now intends to pass legislation that will again detain indefinitely those released under the title of preventative detention.

In the same fortnight the High Court in Great Britain judged illegal the Government decision to send to Rwanda people who had sought protection in England. It was found to contravene the Human Rights Act. The absence of such an act, which had enabled the Australian Government to send refugees to Manus Island and Nauru, provided the model for the Rwanda decision. The Government currently proposes to override the decision by legislating to suspend the Human Rights Act in order to allow the deportations to go ahead.

The common feature to both these events was the immediate rush by Governments to bring forward legislation that further limits the human rights of those affected. In each case the legislation designed to negate the effect of the High Court decisions will be vulnerable again to be struck down on judicial appeal. That haste suggests an initial disregard for human rights and the rule of law by Governments when legislating and an ingrained resistance to any limitation by the Courts of its power. Vindictive laws are used as patches on a rotting tyre at a heavy cost to the integrity and reputation of the mechanics.

It is always fashionable to blame governments for their failures of excess and of neglect. In democracies, however, their behaviour often reflects the attitudes of the people who elected them.

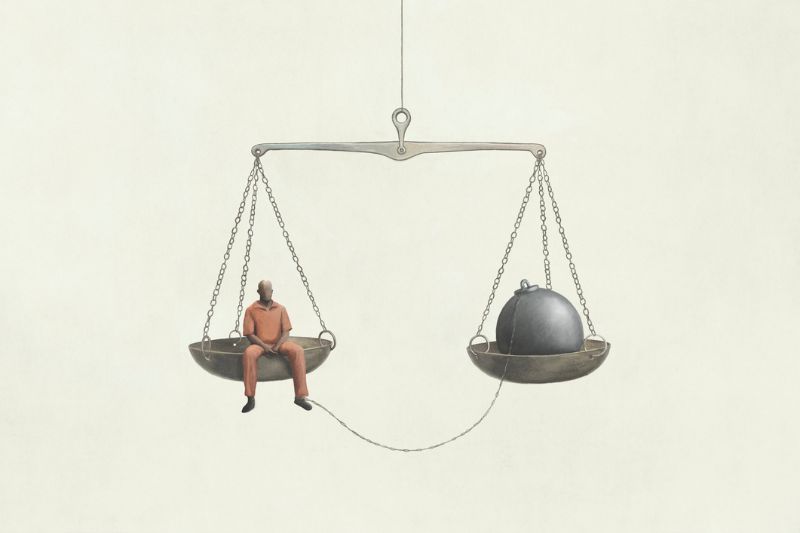

'The kernel of the rule of law in any society has always been the principle of habeas corpus that protects from arbitrary deprivation of freedom. It affirms the value of citizens as human beings not by their qualities or usefulness. To trash this principle by law making devalues the law and ultimately erodes respect for the government that misuses legal processes.'

In this case governments believed that for voters the human rights of others than themselves and the groups to which they belong are not a priority. They could therefore disregarded when they became controversial.

This capitulation to public opinion is not a complete explanation of the response of the United Kingdom and Australian Governments to adverse Court rulings. It needs to be set alongside the authoritarian practices of Governments during the COVID crisis. Governments and people then accepted the restriction of rights of association, of movement, of religious practice and of economic activity in order to halt the spread of COVID. The restrictions were enforced by the justice system. The restrictions of rights were accompanied by the expectation that Governments would also take initiatives to provide housing for the homeless, increase welfare payments and support workers in social services newly discovered to be essential. The ideology of small government, already motheaten theoretically, was set aside.

After Covid the taste of Governments for restricting rights and imposing penalties for violations continued. Draconian laws against protests that would inconvenience the financial interests of large corporations and of government agencies, for example, multiplied.

More recently the legacy of heavy public debt after COVID and the pressures of inflation in societies marked by inequality have confronted Governments with new demands. They are expected to meet public needs at the same time as they reduce their own level of debt. They also face resistance to raising the revenue necessary to meet their social expectations. The commitment by society to the common good notable during the COVID crisis, moreover, has been eroded by the hardships associated with inflation and the shortage of housing. Popular frustration can then lead to hostility to minorities and to groups seen as deviant. Governments, which are the natural target of resentment at harsh economic conditions, are then under pressure to act in unfair ways.

The treatment of child lawbreakers in Queensland and the emergency legislation covering people released from immigration detention are cases in point. So is the proposed legislation to have asylum seekers sent to Rwanda by the British Government, which echoes the Manus Island and Nauru schemes of the Australian Government. They have in common that they respond to political pressures caused by public anxiety about law and order by infringing the human rights of minorities at a heavy social cost.

.png)

This behaviour may seem to be of little significance in the longer term. But it can corrupt both the government’s commitment to good governance and its reputation, as has been the case in Australian Governments since they endorsed a refugee policy based on deterrence. The kernel of the rule of law in any society has always been the principle of habeas corpus that protects from arbitrary deprivation of freedom. It affirms the value of citizens as human beings not by their qualities or usefulness. To trash this principle by law making devalues the law and ultimately erodes respect for the government that misuses legal processes. One hopes that the High Court will again vindicate the principle in the face of fresh attempts by Government to neuter it.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

Main image: Frances Coch (Getty images)