I began teaching in the long-gone days of the overhead projector. Things did not go well at first, so I sought the advice of more experienced practitioners. One of my colleagues had been teaching Maths for longer than was healthy, either for him or his students. He had been in the air force during World War II and always referred to the kids as the ‘enemy’. He could tell you to the day how long it was until his retirement. His advice was to make sure I was always in the classroom first. He had seen too many struggling teachers start to turn up late.

‘Don’t give an inch,’ he said. ‘It’s your turf and you have to defend it.’

An equally seasoned Maths teacher gave me the same advice, but for the opposite reason.

‘I always try to be the first in the room,’ she said. ‘Then as the students arrive, I try to catch the corner of each person’s eye. I just make that human contact, eye to eye. As I do so, I remind myself that those students are bringing their whole world into the room with them. They have all sorts of experiences, good and bad. I remember that who you are teaching comes before what you are teaching.’

I think of those two teachers as we approach the start of another school year. The entire community has an enormous investment in what happens in classrooms and in the wellbeing of both students and teachers. It is usual to focus on kids starting school. Let’s also spare a thought for the hundreds who are about to start their careers as classroom teachers. They are entering a career that has never been more important and never been less understood. I fear it is being strangled to death.

A young friend of mine left teaching after about four years. She had been an excellent primary teacher in a school with many challenging kids, with whom she developed a rapport and whose literacy and numeracy skills improved because of that.

‘I gave up,’ she told me. ‘I wanted to be a teacher, not a data collector.’

'More than anything else, I hope that new teachers will enjoy themselves. The job is supposed to be fun. Hard work, but fun. We need a school culture that will help teachers discover the joy of their calling.'

The bureaucratisation of teaching has exhausted the primary resources on which schools have relied for generations, namely goodwill and generosity. There isn’t much of either left in many places. The hypersurveillance of teachers prevents them maturing as practitioners. Teachers are more likely to become compliant than creative.

Teaching is not about ticking boxes. It never was. It is about helping young people develop the skills they need to deal with the core questions at the heart of education: what does it mean to be alive? and who or what is a human being? You can’t lay a hand on these questions without literacy and numeracy. Nor without humility and an appreciation of the long learning traditions of the human family. The teacher is the adult in the room. They can’t rise to this challenge when they are themselves treated like children.

The core business of school is to enable young people to discover their compassion. This is the work of both mind and heart. In my experience, it happens in at least three ways.

First, each child needs to appreciate that they matter and that it matters that they learn. The relational aspect of teaching is an investment in the dignity of the young. My first principal told me, when I was photocopying endless resources to defend myself, ‘Remember, you are paid to talk to kids.’

Second, students need to understand that the world is a big place and that they are not the centre of it. An encounter with the needs of the planet and the whole of the human family saves us all from catastrophic self-regard. School gardens, visits to retirement facilities and facing the malaise of global poverty are key formative experiences. Thinking about what it means to live only makes sense if we are thinking about what it means to live justly. This can be painful, but education is not supposed to be an analgesic. An overcrowded curriculum can have that effect. It doesn’t allow time for specific passions to develop. School should help the young discover their prepositions: where are they from, what do they stand on, who are they with, what are they for?

Finally, compassion comes from being able to make a home in complex narratives. It is understandable why people want to explain reality in terms of bumper stickers and slogans. The world is messy and making sense of it is easier if you turn colour into black and white. The beauty of passionate teaching is that it builds bridges beyond that: science, literature, media, geography, history, philosophy and art are among the complex narratives. They slowly allow students to find their way into deeper water.

One of the teenagers in the British sitcom The Inbetweeners refers to teaching as a ‘graveyard for the unlucky and the unambitious’. In one form or another, this is a common perception. Nothing could be further from the truth. More than anything else, I hope that new teachers will enjoy themselves. The job is supposed to be fun. Hard work, but fun. We need a school culture that will help teachers discover the joy of their calling.

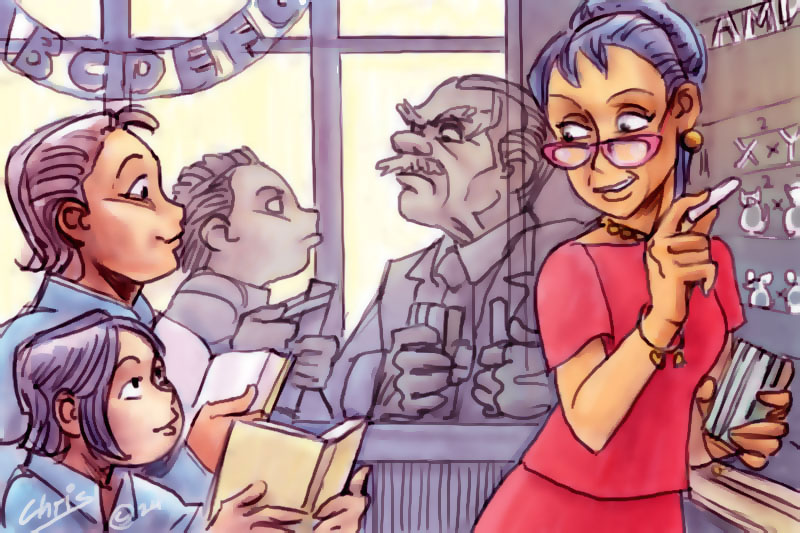

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.