In the lush back garden, a gardener works. He is pulling up weeds, trimming back wayward branches, sprinkling fertiliser on the fuchsias to keep them red and plump. Sunlight filters through green leaves. My new friend, a member of the congregation where I am Minister, shows me a place where she likes to sit; an old fold-out chair sitting in the doorway of a kind of botanical annex to the house, filled with glistening plants and beloved ornaments. ‘My mother used to sit here too,’ she said. ‘She called it her paradise. I like to sit here and read and listen to the birds.’

We go into the kitchen for a cuppa, and my new friend calls the gardener in too. She makes him a cup of coffee, just the way he likes it, and he takes a cake from the plate of goodies, cuts it into little slices and places it in front of her. They go on day trips together, these two. She goes to his family functions and his grandchildren hug her like she’s their grandma. It’s a friendship that has sprung up, by chance it seems, because my new friend needed some help in the garden. It’s as lovely and unexpected as a petunia sprouting up in the lawn.

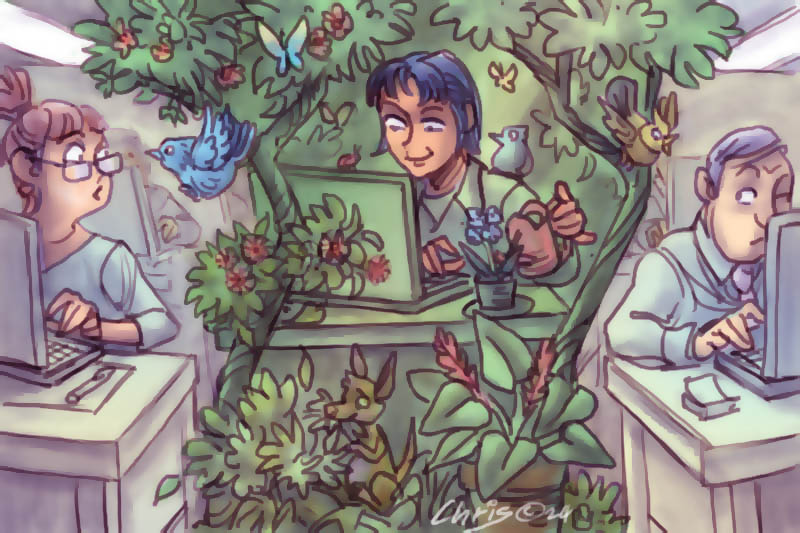

I feel like I am witnessing, during this visit, a delightful, easy interplay between work and rest. I am reminded of an ancient story about God walking around the garden in the cool of the twilight hours, talking with the humans God has just created. It’s a story about the creativity that animates a gardener’s hands, about the mystery of sunlight and water that takes a person’s labour and turns it into a garden. And it’s a story about a God, and people, who stop to rest: to breathe in the damp, fragrant evening air, to delight in friendship and conversation.

In church we are thinking about rest and sabbath, and so I have been listening to Tricia Hersey who wrote Rest is Resistance, and who has created performance art in which she, as a Black American woman, napped over rows of cotton plants. Because her ancestors were not allowed to rest; their bodies were enslaved to a money-hungry, racist machine. She is resting now on their behalf. She is resting for her ancestors. Rest, or sabbath, was instituted by God to newly released slaves. Rest, then, has deep relevance to modern day slaves, and their freed children.

Tricia talks about ‘Grind Culture’: in which productivity and continued economic growth is valued above anything else. In Grind Culture, work is more important that family, than relationships, than community. Like the Israelites were enslaved to Pharoah, many of us today are enslaved to Grind Culture, and wear busyness like a badge of honour. I think of those of us who literally have no time to rest, because we are looking after small children and trying to hold down a job, or two jobs, to make ends meet. I think of migrant people who work long hours for little pay, in the hot kitchens of our restaurants, driving our Ubers, delivering our meals, working endlessly just to survive. There are many ways in which we can be enslaved to Grind Culture.

'It means supporting measures to reduce the cost of living. It means campaigning against companies that exploit workers, and investigating supply chains that use slavery and exploited labour to produce their products. There is much work to be done, in order that we might all rest.'

How can those of us enslaved to Grind Culture recover rest? The answer is not more ‘me time’ and trips to the day spa. It is not expensive holidays for the few who can afford it. Like the Sabbath that was instituted for a whole people group (including their servants and animals and even the migrants in their midst), we must recover a collective form of rest as well. This means supporting workers who demand time off, and decent pay so they don’t have to work so much. It means supporting measures to reduce the cost of living. It means campaigning against companies that exploit workers, and investigating supply chains that use slavery and exploited labour to produce their products. There is much work to be done, in order that we might all rest.

But today, we rest: in the shade of a tree-filled backyard, in the warmth of unexpected friendship. Today, I am aware of how precious, how sacred, this rest is, the way it is robbed from us, and the work we need to do to get it back.

Andreana Reale is the Minister at Murrumbeena Uniting Church.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.