There’s a priceless moment in the winkingly-titled documentary Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary. It’s an audio recording of a very short phonecall, where the film’s director, Garret Price, is asking Donald Fagen from Steely Dan whether he would be open to being interviewed.

‘What’s the genre?’ asks Fagen.

‘Yacht rock,’ says Price.

‘Oh, yacht rock,’ says Fagen. ‘Well, I tell you what. Why don’t you go fuck yourself?’

And then he abruptly hangs up.

Although Price – along with many other worshippers at the altar of yacht rock – claim that Steely Dan are, as one person in the doco puts it, ‘the primordial ooze from which yacht rock sprang’, it’s a term that comes with a lot of baggage. And it’s baggage Fagen is obviously not keen to carry.

But what exactly is yacht rock? And why doesn’t Fagen want anything to do with it?

There’s the vexed question of what is yacht and what is not. The creators of Yacht Rock are very serious about the line in the sand that must be drawn. One of the series creators says that ‘almost all yacht rock is soft rock, but not all soft rock is yacht rock.’

Well, it’s complicated. For a start, in its heyday, from the mid-’70s to the early ’80s, it was not called yacht rock. It was variously called soft rock, west coast rock or AOR (adult-oriented rock).

It was slick, smooth and glossy, and came out of the US, much of it from L.A. It was highly produced and played by skilled musicians, many of whom were session musos who could play just about any style of music on demand. It was a little bit pop and a little bit rock, but was heavily influenced by soul, jazz and R&B.

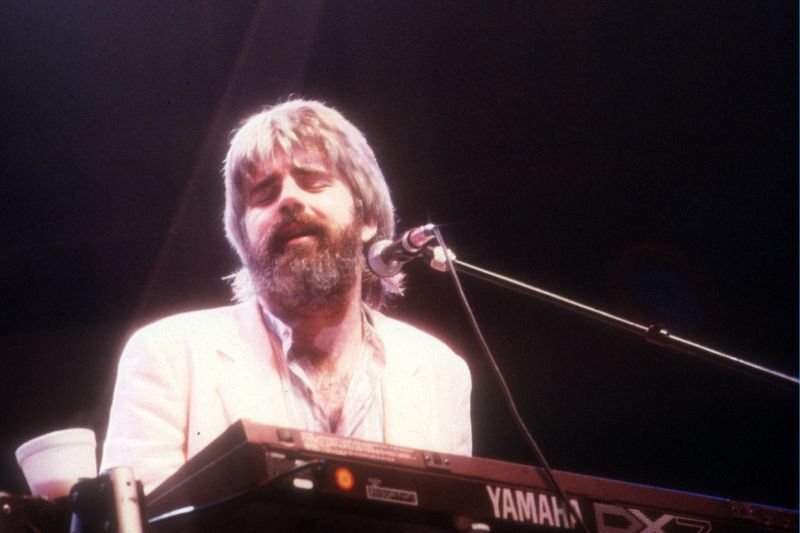

If one person personifies yacht rock, it’s Michael McDonald. And if there’s one song that encapsulates the genre in three minutes and 41 seconds, it’s 1978’s What A Fool Believes, which McDonald co-wrote with Kenny Loggins and sang with The Doobie Brothers.

In fact, the lilting piano line, which has come to be known as the ‘Doobie Bounce’, was all over pop music for a few years. In the doco, they play snippets of song after song that appropriated the sound, and the way they’ve lifted McDonald’s style is jaw-dropping.

Meanwhile, McDonald’s voice, a bear hug of a thing that is high in register, husky in texture and warm in tone, seemed to dial in to exactly the right frequency that whispered ‘yacht’.

As comedian and musician Fred Armisen says in the documentary, ‘Yacht rock to me is a very relaxing feeling. The singers all seem to be saying Hey, it’s going to be okay.’

The genre has echoed through the canyons of popular culture. As Christopher Cross’s Ride Like The Wind plays over the opening credits of Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary, we see clips of the music being referenced and used in Jeopardy, Family Guy, The Sopranos, 30 Rock, The Simpsons, Breaking Bad and The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.

And the musicians who created it were seemingly everywhere at the time. The members of Toto were on everything from Boz Scaggs’ Silk Degrees to Michael Jackson’s Thriller, along with having their own megahits such as Hold The Line, Rosanna and Africa.

As well as leading The Doobie Brothers, McDonald was for many years a member of Steely Dan, as well as lending his keyboard playing and vocals to fellow softies Loggins, Stephen Bishop and Christopher Cross.

The doco makes a few revelations about Cross that may surprise people. It turns out the portly singer with the high voice and perm-like curls, who seemed like the very definition of ‘dag’, was such a good guitarist that he subbed for Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore on their first US tour when Blackmore was ill. He also admits that he wrote Ride Like The Wind while on an acid trip.

The genre sank in the 1980s just as MTV rose. As the good-natured McDonald says, ‘When videos came along I felt like one of those silent screen stars entering the realm of the talkies.’

But a couple of decades later, in 2005, something weird happened. A group of struggling L.A. comedians, who had been rescuing all these soft rock albums from the bargain bins of record stores and revelling in the retro sound and artwork, made an online comedy series. They dressed in Hawaiian shirts and sailor hats, playing fictionalised versions of McDonald, Cross, Loggins and their ilk.

They named the series after the term they coined for this music – Yacht Rock. It became a cult show. And then things snowballed.

All parody comes from an obsession with the thing you are parodying. You have to know something inside out to accurately make satire.

For instance, there’s the vexed question of what is yacht and what is not. The creators of Yacht Rock are very serious about the line in the sand that must be drawn. One of the series creators says that ‘almost all yacht rock is soft rock, but not all soft rock is yacht rock.’

They consider Michael McDonald, Toto, Christopher Cross, Kenny Loggins, The Doobie Brothers and – yes, sorry, Mr Fagen – Steely Dan to be yacht rock.

But as for Air Supply, Rupert Holmes, Jimmy Buffet, Fleetwood Mac, The Eagles and – somewhat controversially - Hall & Oates? Not yacht rock, according to the series creators, despite songs from those acts often showing up on yacht rock compilations and playlists.

Many of them also show up in the repertoire of the brilliantly named LA tribute band Yächtley Crëw, who formed in 2017 and are touring Australia in May. Yacht rock bands, theme nights and parties have become a thing over the last decade, part parody and part true love, a dichotomy that stems from the web series.

As Amanda Petrusich, music critic at The New Yorker, says in the documentary, ‘The fact that the term emerged from a comedy show did have a really big impact on why the music is now ironically appreciated, when in fact I think the records they were making were entirely sincere and honest and pure.’

The church of yacht rock is now a big one that only seems to be getting bigger, a place where you can indulge your inner dag by dressing as a sea captain or a Florida retiree on a cruise ship, and then rock – ever so softly – to some of the smoothest, cruisiest music of the last half century.

If yacht rock has a message, it’s this – there’s a party and everyone’s invited.

Apart from Donald Fagen, of course.

Barry Divola is an author, musician and journalist who writes regularly for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. His latest book is the novel Driving Stevie Fracasso. Follow his writing at: authory.com/BarryDivola

Main image: Michael McDonald, ca 1970. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)