Three core insights came together for Fr Pedro Arrupe when he launched Jesuit Refugee Service 30 years ago this week. The first compelling factor was his compassion for the refugees in their suffering. '... last year, struck and shocked by the plight of thousands of boat people and refugees, I felt it my duty ...' he wrote to the Society on 14 November 1980. For Arrupe the refugees were 'signs of the times', a feature of his historic time that compelled a compassionate response.

Three core insights came together for Fr Pedro Arrupe when he launched Jesuit Refugee Service 30 years ago this week. The first compelling factor was his compassion for the refugees in their suffering. '... last year, struck and shocked by the plight of thousands of boat people and refugees, I felt it my duty ...' he wrote to the Society on 14 November 1980. For Arrupe the refugees were 'signs of the times', a feature of his historic time that compelled a compassionate response.

Second, having been Superior General already for 18 years, he had a strategic sense of how the Society worked and what it was capable of: its mission, structure and strengths. 'This situation constitutes a challenge we cannot ignore,' he wrote, 'if we are to remain faithful to St Ignatius' criteria for our apostolic work and the recent calls of the 31st and 32nd General Congregations.'

Third, Pedro Arrupe had confidence in the goodwill and resourcefulness of the many partners willing to share in the same mission — 'the active collaboration of many lay people who work with us'.

Those same elements have helped to build the world wide project that is JRS today. If any of these elements is missing now, JRS would fall apart. First, JRS is inspired and instructed by the lives and experiences of the refugees — their lives inform our prayer, our discernment and planning, our way of proceeding. Second the Society, as a global body present in over 120 countries, adapting and trying to learn from each local culture, has a mission that is universal, to go by preference to frontier places, to serve a faith that does justice. Third, many friends and partners join this mission and make it possible. Many would never come to know us, and we them, if it were not for our shared solidarity on behalf of people in distress. They bring the five loaves and two fish that feed hungry multitudes.

In exploring with you the insights of Fr Arrupe embodied in the JRS, I want to explore each of these three elements, and put them at the heart of our 30 years celebration.

Part I: The refugees

All associated with JRS will tell you: 'the refugees are our teachers'. From them we learn much. As an organisation, Jesuit Refugee Service was built from the bottom up. Experiences in the field and reflection on those experiences gave JRS its shape. Its vision came from its founder Pedro Arrupe, certainly, its horizons are shaped by our reading of the Gospel, but each new program is worked out on the ground with the people we serve, fitting their needs and mobilising their resourcefulness. Structure is not the end itself but rather a means to service. JRS had to be structured so that it could be true to its mission to 'accompany, serve and defend the rights of refugees'. Yet we can own that mission because it is verified in our lived experience on the ground. For example the experience of accompañamiento for JRS workers in Central America gave new resonance to the meaning of 'being with'. When North Americans volunteered to live with communities of refugees in El Salvador, local military knew that if and when they used US supplied M16s against those communities and if any American citizens were harmed, then military aid and external political support for the dictatorship would dry up. Just by being there, by accompaniment, one could protect human rights.

Looking through the eyes of the people we serve we are given a fresh view, a quite new perspective, sometimes of joy, sometimes of shock. Forever after the world is a different place. I met a Rwandan woman, whose husband was taken by the civil war, whose oldest son was also caught and killed by neighbours, yet she will still cook and bring food for her neighbours, whatever they have done. She goes on dreaming of a world without war. Now I can know that peace is really possible. I met a Sudanese woman whose neighbour was dying of cholera. She simply took the neighbour's child despite risks to herself, and nursed the child to life. From her I now know what compassion really is. I met a Vietnamese woman who forgave, face to face, and in front of many people, the man responsible for the death of her sister and two of her children. Later she found her husband who had fled by a different route, and they started their lives together again. In a Thai camp I met a woman who looked after her two surviving children plus 20 orphans. Eight other children and her husband had died in Cambodia. She wanted to forgive her husband's killer and she prayed for the peace of her country. These women give reconciliation fresh sense. Every day in every camp, every detention centre, and in urban refugee settings, JRS people hear stories like this. Our primary service is to listen to the people, and by listening, to help them find courage to go on with life. What we have seen and heard changed our lives.

From refugees I learned that if you want to a shape a vision of the future society for which we long, then go to the widows and mothers who have lost their sons and husbands to war. Those who have nothing left to lose are often the ones most free to imagine and to describe an ideal society, and they show extraordinary resilience and hope in pursuing their vision. 'If it were not for hope,' the proverb says, 'our hearts would break'.

A refugee story

May I tell you about one refugee whom I met during the 20 years I lived and worked JRS? The story has no happy outcome, indeed far from it. But it may help to communicate some of the feelings that inspire many who accompany the refugees.

Gabriel, a six-foot-six Dinka, had arrived in Thailand after a journey that for his people rivalled Marco Polo's. Travelling by foot to escape the fighting which had begun in 1983 in his home in Southern Sudan, he had crossed to Egypt and on to Iraq to study, but instead was drafted to be a porter in the Iran-Iraq war of the eighties. Escaping, he failed to get passage westwards to Europe and so, heading east towards Australia, was stopped in Singapore and diverted to Thailand. There I found him, culturally disoriented, lonely and desperate. He visited me frequently, and with an officer from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), we searched everywhere for a country to take him. Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada, Sweden, none would even interview him. Finally he was offered three choices, a trip home to the Sudan, or Kenya, or Liberia. In desperation he accepted Liberia and departed in 1988. Several times he wrote to me, his words dictated to a Scottish Salesian priest. A few years later I was in my new position in Rome. Disturbed by the suffering of the Liberian people, I went in 1991 to war-ravaged Monrovia to see what could be done. While there I also hunted for Gabriel. Visiting the Salesians, I asked if they had known him. Sure enough, they pointed me to a Scot, the one who had written Gabriel's letters. He told me how Gabriel had died, mistaken for a Mandingo, waving his long arms and showing his refugee card, trying to explain to a drugged, over-armed Krahn follower of Charles Taylor, that he was 'under the protection' of the United Nations. I wept for Gabriel and the many victims of that senseless never ending war.

Perhaps there is no moral to draw from the story of Gabriel who had traversed, mostly on foot, the geography of our world of conflict and refugees: escaping the Sudan war, caught in a Middle East one, blocked when trying asylum routes west, east, south and north, floating in the eddy of the Indochinese refugee tide, finally a target in someone else's war. But try to imagine this. Almost all of the 145 or more countries which have signed the Refugee Convention, including my own homeland, Australia, have policies of tightening their borders. As a result some 80% of the world's displaced now live in the global south. Many, blocked forcibly on their journeys, are held in detention for years.

In this lecture I do not offer an analysis of the global refugee problem, but remain with Pedro Arrupe's inspiration and with what JRS and the Society has learned from the refugees. Try to penetrate the spirit and mind of Fr Arrupe, try to understand how his compassion for the sufferings of people inspired such a strong movement of solidarity. An article of Pedro Arrupe on the Heart of Christ, written in the same year as he founded JRS, gives some insight, I believe. It is called 'The Heart of Christ, Centre of the Christian Mystery and Key to the Universe'. In that he quotes the Evangelist John in his first letter. John's language, Arrupe writes, 'becomes concrete and incisive when he asserts that such love would be inconsistent 'if a man who was rich enough in this world's good saw that one of his brothers was in need, but closed his heart to him, how could the love of God be alive in him?'' (1 John 3:17).

The Ignatian spirituality at the heart of Arrupe's compassion for those in need is at the heart of JRS. First, by listening to the voices of these people, by contemplating the word of God, we believe one can actually find God in all things. Every encounter, every experience, every choice is an occasion of grace. Second, spiritual depth, interiority: rehearsing our decisions in the imagination, we seek openness of heart to welcome the desire of God. Third, from this practical mysticism, one is free to commit oneself for service and action in response to the greatest and most urgent of needs.

In his last talk to the Jesuits in Thailand, Arrupe pleaded for Jesuits to pray constantly, to be guided by the Spirit, and to seek close union in every way, since refugee work is front-line work where conflict and hostile ideologies are to be expected.

My Sudanese friend Gabriel was one of the 'unheard'. Refugees' voices are often unheard, unheeded, effectively silenced. Yet they are the gentle breeze, the still small voice of the presence of God of which we read in the story of Elijah. The one who accompanies refugees must know how to listen to the unheard, to the softly spoken. As Martin Luther King said: 'a riot is at bottom the language of the unheard.' The unheard are everywhere.

Listening to the refugees, learning like Elijah to know the presence of God in the whispers from the edges of society, we hear the message that another kind of world is possible. This helps us overcome the normal temptation to consider refugees as helpless, and to respond instead with solidarity. This is the revolutionary challenge of the Beatitudes: the call to a hard and disturbing love:

Blessed are you who are poor. Woe to you who are rich.

Blessed are you who are hungry. Woe to you who are full.

Blessed are you when people hate you, exclude you, revile you.

Woe to you when all speak well of you.

Refugees are people whose choices have been taken. For those who do choose to take their side, there is only one way forward, which is to listen and to learn from them, and to make tools, such as education, available to them, and to empower them to seek their rights. It is not enough, according to the logic of the Beatitudes, to accept the imposed solutions of the powerful.

Pedro Arrupe's heart would go out to a person such as Gabriel. The vision he offered through JRS is an experience of the Gospel contradiction: a hope that sustains the unheard across the globe. This is the 'hope against all hope' of which St Paul wrote. It is a hope embedded in the smallest and humblest of daily struggles, a hope joined at the hip with the struggle for a different kind of world. To join JRS is to embark on a journey of faith in the company of refugees.

Part II: Don Pedro Arrupe: how the Society works and what is its mission today

The second part of this talk is about Pedro Arrupe's appreciation of the Society as a global body, in the globalised world even of thirty years ago. His insights into how the Society can work as a global body comprise the second element of what made JRS work then and now. In launching JRS he called on all he had learnt in his years as General about the Society's mission and about how the Society worked. He set up JRS as a supranational network, able to draw on the local knowledge of Jesuits and friends in many places, joined with the ready support of friends from around the globe.

They say that you can tell how big a person is by what it takes to discourage her or him. In which case, Fr Pedro Arrupe was a person of huge spirit and enthusiasm. Although for twenty years I sought to interpret and implement his vision, I met him on but three occasions, each memorable. First in mid-1980, in a half hour encounter he explained with some passion how good it would be for the Society to enter wholeheartedly in service of refugees. He mentioned nothing of the trip he was to make later that morning to his homeland to meet a faction of the Jesuits in Spain who wanted to break from the Society and from the renewal he initiated and symbolised. The second encounter was in Manila in early August 1981, a few days before his cerebral stroke, when he asked me directly to join this new project. On the third occasion, in the mid 1980s, he was imprisoned by his stroke in the Jesuit Curia's infirmary. Not able to speak, his shaky left hand drew a map of India with the droplet shape alongside. Tapping Sri Lanka, he clearly asked for news of the conflict and the refugees there and what we were doing for them. The suffering of the refugees continued to animate him in his years of silent prayer.

As Superior General, Pedro Arrupe guided the Society through the renewal initiated by Vatican II. He called a General Congregation in 1975, whose most influential document was Decree 4, 'Our Mission Today: the Service of Faith and the Promotion of Justice'. The core of the text runs as follows: 'The mission of the Society of Jesus today is the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement. This is so because the reconciliation of men (and women) among themselves, which their reconciliation with God demands, must be based on justice. [GC32, Decree 4]

The challenge to understand this text and put it into practice is still with us. The Society renewed its commitment to this expression of its mission recently in GC35 with a fresh statement of 'reconciliation with God, with one another and with all creation'. We meditate it, renew our understanding, and try to make practical decisions in the light of it. The truth of the text is proved by its martyrs ... murdered by people antagonized by those who live out a faith that does justice. JRS has many brothers and sisters who have given their lives in the course of their service. We honour them too in this anniversary.

Following GC32, in the second half of the 1970s, somehow there was too much resistance to Decree 4. Jesuits could discuss for hours on the definition of the word 'justice'. There were bold and wonderful initiatives, but wholehearted, corporate commitments were still too rare. Cooperative efforts faltered on ideological differences, or human problems remained just intellectual challenges. Arrupe saw this but did not appear discouraged. Michael Czerny, who for many years was Secretary for Social Justice in the Jesuit Curia in Rome and subsequently developed a magnificent network in Africa serving HIV/AIDS survivors, always claimed that Don Pedro initiated the Jesuit Refugee Service as an attempt to promote a different methodology for the Society in response to injustice. A simple statement of mission was not enough. We needed imaginative connections between that mission and the situation of people today who suffer injustice. We needed models of how our faith in God's action in our world can connect with the hardships of people. The service of refugees offered such a tool. In the service of refugees there is a place for everyone. Compassion is the driving force, not ideological purity. Reflection is important, analysis is indispensable, advocacy is inevitable, yet in the end there are people right in front of us whose needs are clear, and to whom we must respond. JRS offered ways for all to engage and to learn from their lived experiences.

A key to understanding Pedro Arrupe is Hiroshima: where he was in 1945 when the bomb fell. He likened the refugee crisis to the way the atomic bomb not only affected its victims, but also impacted then and now on the consciousness of the world. Michael Campbell-Johnston described Fr Arrupe's last public engagement as General in Bangkok, on 6 August 1981, the anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima. He writes:

August 6 was the Feast of the Transfiguration. Sixteen of us spent all morning with Fr General discussing our apostolate to refugees. It was an excellent and at times moving meeting in which there was wide agreement that our way of proceeding should consist essentially in a ministry of presence and sharing, of being with rather than doing for. Our value system and lifestyle is different from that of professionals. From our poverty (few funds, little expertise, no transport) we were powerful and able to give the people a sense of their own worth and dignity. At the end, Fr Arrupe gave a remarkable impromptu talk, speaking of a message he would like to be his 'swan song for the Society'. He spoke of his memories of the atom bomb at Hiroshima which had exploded 36 years ago that day. After a farewell meal, we accompanied him to the airport and saw him off on a direct flight to Rome. None of us would ever have imagined that this was to be his last working day as General. It was on leaving the plane and passing through Immigration at Fiumicino that he had the stroke that left him with impaired speech and partially paralysed.

Rowan Williams, in his speech to America Magazine accepting the Campion prize for his efforts in ecumenism, spoke of how he prepared for a visit to Japan by reading Fr Arrupe's writings on his experiences in 1945. 'And as I read, I began to understand more and more deeply how someone formed in the Jesuit tradition that was Campion's could see into the heart, into the depths of evil, and yet see beyond. In the face of unspeakable inhumanities, Pedro Arrupe was able to witness to the humanism, the depth of hope, which is the proper contribution of Christians to culture and politics and ecumenism.'

Although Pedro Arrupe set the vision of JRS in place, it was Peter-Hans Kolvenbach who, as Superior General for over 24 years gave JRS its real place in the Society. From his experience in Lebanon, where his own office had been bombed a number of times, he understood this service. How to describe him? A professor, a monk, a man of fascinating conversation and dry wit, he listened, encouraged, defended and urged JRS. Each month for over ten years, or more frequently if there was any crisis, I would meet him and explain our challenges. When I began in Rome and asked for instructions, he simply commanded, 'Do something for Africa.' It was instruction enough. Another time I came to complain to him that we had wonderful people working for the JRS, but sometimes the hardest to move were the Jesuits. 'Yes,' he commented, 'they say the same in Fe y Alegria. But of course without the Society, this work could not be done.'

It was Fr Kovenbach who extended the call of concern for refugees to every Jesuit. He claimed in 1990 that the response of Jesuits to the Service had already been 'magnificent', and added: 'The Society's universality, our mobility, and above all our apostolic availability are the qualities rooted in our tradition which should help us to meet the challenges offered by the refugee crisis of our time.'

The third Jesuit General under whose guidance JRS is now going forward is Fr Adolfo Nicolás, who constantly returns to three themes: the universal mission of the Society, that is its call to go to the 'frontiers'; depth of the Spirit; and creativity. Each of these themes reflects the mission given to JRS already 30 years ago.

Part III The world wide network of Collaborators who make up the JRS

In this third part of this afternoon's reflection I want to speak of the wide network that has been animated by Fr Pedro Arrupe's vision and initiative. Arrupe saw JRS as a 'switchboard' connecting identified needs with offers of assistance. He was sure that the Society could rely not only on the cooperation of its own members and communities, and not only on the parishes, schools and other institutions under its care, but also on the generosity of our many friends, especially religious congregations and lay movements. Let me quote two remarkable, yet typical women who have each been working with JRS for over 20 years.

First, Sr Denise Coghlan a Mercy Sister in Cambodia:

Pedro Arrupe called for a response of love and service to the needs of people forced to flee their homes after the cluster bombs, guns, rockets, and chemical weapons ravaged Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Much earlier he had tended the injuries of innocent sufferers from the atomic bombs dropped in Japan. From this call grew JRS.

Thirty years later, and I have been part of it for twenty three of those years, JRS is a network of friends, or indeed many networks of friends which include refugees, people who serve among refugees, academics, human rights advocates, the public who support the work from afar, and in some places government and UN officials. The hope of all is that those who flee may live in freedom and dignity.

For many of us it has been an experience of meeting God in the most unlikely places and being blessed by some of the poorest people in the world. It has been listening to incredible stories, most of them true! It has been a place where involvement at the grass roots and advocacy at the highest level has worked together unto good. It has enabled the voice of survivors to be heard and international treaties to be negotiated. To JRS I owe many wonderful friends, experiences I could not have imagined, and an admiration for the power of the human spirit to rise.

The second testimony is from Sr Marie Jeanne Ath, of the Sisters of Providence de Portieux, who also joined JRS over twenty years ago. She was the only Cambodian religious to survive the genocide of Pol Pot. This trip to Europe gave me the opportunity to visit her in France where she is under treatment for an aggressive cancer. She recently spoke these words to a friend:

What I remember most from JRS was the great team both at the border camps and in Cambodia. The team gave me the energy to support my work among the poor. I loved the grace of being among the poorest ones but even more I remember the team and the Masses and sharing of life and faith that was so clear among us.

We did not speak it out in many words but lived it together. Love was what bound us together and urged us on. The team gave me hope and a home and encouragement and laughter, and the opportunity to serve and accompany and advocate.

Now I am not able to eat and not able to sleep, much like many refugees and asylum seekers and poor families. Here they give me things for the pain. I send a big love to everyone in JRS all over the world but especially to the ones who have known and loved me and I have known and loved in JRS since 1987. Have courage.

With only a tiny contribution by Jesuits, JRS makes possible the courageous, collaborative efforts of hundreds of co-workers, lay and religious, and thousands of refugee co-workers. In addition, JRS has magnificent partners in the global federation of Caritas agencies and other non government organisations, especially the Catholic and other faith based bodies that give immense financial support, advice and encouragement to its work. The local Churches are partners on the ground. The world wide networks of Jesuit educational institutions provide a ready social base to JRS. JRS has many friends to in governments and in the international organisations, who respect the mobility, the credibility and the wisdom of a body that is on the ground among the refugees, and that can reflect, analyse and propose policy that can lead to breakthroughs, or can oppose destructive policies intelligently and in an informed way.

Our most recent General Congregation recognized that the Society can only go forward if it will collaborate with others. By necessity we seek to enable partners find their rightful place in the mission of the Church and in the Society's mission. In this we return properly to Ignatius Loyola's own way of working. He found many friends who joined with him in mission. He formed organisations of lay people to carry on the work he initiated for the homeless, the beggars, the prostitutes and the delinquents. In today's complex, globalised world this is the most appropriate way for Jesuits to work.

Conclusion

In this account I have hardly spoken about the historical development of JRS from almost random undertakings into a coherent international body with a robust yet flexible structure, a hub in Rome, ten regional centres with the autonomy to take initiatives, and a presence in over 50 countries. Its impact derives from the credibility of its presence in the field. I have not spoken of the dramatic changes in the world of forced displacement, of the time before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, or when 'communism' was replaced with 'terrorism' as the enemy in the mind of the West. In these thirty years the population of the world has risen from 4.4 billion in 1980 to almost 7 billion in 2010. Today there are fewer places for refugees to go.

Returning now to a new assignment in Asia Pacific where I accompanied refugees in the 1980s I find new categories of forcibly displaced persons. Displacement in Asia Pacific today is caused by conflicts, poverty, inequality, poor governance, and by disasters for which often the preparations have been totally inadequate. Refugees and other migrants often use the same routes, use the same 'agents' or smugglers, leave behind the same oppressive human rights situations. The term IDP — internally displaced persons — was only invented in the 1980s and came into use in the 1990s as more and more victims of conflict were unable to leave their countries. Undocumented workers, stranded migrants, trafficked persons, especially women and children, have all increased. Thailand alone holds over 3 million stateless persons. Victims of natural disasters are many, such as the 7 million still homeless following the recent Pakistan floods. Those affected by earthquakes, cyclones and tsunamis grow in number, often because development is uncontrolled, especially in the coastal estuarial cities of Asia.

These are new challenges for the mission of JRS, since it is not necessarily restricted to a tight mandate like a UN agency, but rather its mandate arises out of its compassion for the victims of disaster. JRS, since its beginning designed as an integral part of the life of the Society, derives its identity from the inspiration of lived experience with refugees and the priorities set out in its Constitutions: Who are the most forgotten, unheard, not accompanied? Who are not served by others? Who can we serve best with the means available to us? JRS integrates a spiritual calling with the vocation to serve the human family. As religious we live poorly so that all who meet us will know that God is our treasure, and those who are in destitution or who fear for their lives will find a friend in us.

Our Church today is in crisis wherever it fails to hear and understand the hunger of people for meaning. Pope Benedict XVI called the Society of Jesus to reach out to this hunger, to go those 'frontier' places where the Church finds it difficult to go or cannot go. By definition, refugees are there at the 'frontiers'. This mission offers many opportunities. When offering this challenge and invitation, Benedict spoke about JRS in his message to General Congregation 35: 'Taking up one of the latest intuitions of Father Arrupe, your Society continues to engage in a meritorious way in the service of the refugees, who are often the poorest among the poor and need not only material help but also the deeper spiritual, human and psychological proximity especially proper to your service.'

The JRS story is about the lives and hopes of people whom we know personally. JRS opens a door of insight, beyond transitory and shocking images, into the inspiring efforts of people to defend their rights, protect their families and give their children a future. Fr. Arrupe was a prophet. His vision for JRS has not only given great service to people in need, it continues to bring wisdom and blessing to the Society and to all those who, through it, meet the displaced, dispossessed and 'unheard' people of our world.

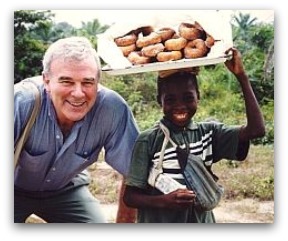

Fr Mark Raper SJ is President of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific. The text is from the First Annual Pedro Arrupe Lecture, 'The world mobilised: The Jesuit response to refugees', which he presented on 9 November 2010 at the Gregorian University, Rome. Mark is pictured in 1998 with a refugee in Liberia.

Fr Mark Raper SJ is President of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific. The text is from the First Annual Pedro Arrupe Lecture, 'The world mobilised: The Jesuit response to refugees', which he presented on 9 November 2010 at the Gregorian University, Rome. Mark is pictured in 1998 with a refugee in Liberia.