In November a few years ago, I received a phone call from a gentleman named Mark Feary. He said he was the curator of the Silvershot Gallery in Flinders Lane in Melbourne at the back f St Paul’s Cathedral. He said that over the previous three months he had been curating an exhibition centring around the themes of ‘Life’, ‘Death’ and the ‘Thereafter’. In September the theme of the exhibits had been ‘Life’, in October, ‘Death’, and in November, ‘Thereafter’.

The exhibition was closing at the end of November, and Mark’s intention was to compose a retrospective catalogue. He had asked a doctor to write a thousand words on ‘Life’, an undertaker to write a thousand words on ‘Death’, and he was looking for a priest or minister to write something of a similar nature on the ‘Thereafter’. Was I willing to help?

With some misgivings I agreed. I thought, however, that I might find some inspiration if I actually visited the gallery before the exhibition closed. So, one Saturday morning in that same late November, I climbed up three floors to the Silvershot Gallery to view the exhibition. The gallery was dominated by a huge yellow quasi-chandelier. When I asked the attendant, he told me that it was the work of an artist named Blair Trethowan and that it was entitled ‘Change’. He also told me that Blair had recently passed away.

When I came back home, I composed the following. I hope it has some relevance to our hopes, expectations and even our doubts.

Thereafter

Have you ever waited prone and nervous on a trolley outside the operating theatre for a serious, or even a mildly serious, operation? Apart from the exiguous theatre smock, you are stripped, shaven even, virtually naked. You have heard stories of clinical misadventure where, for minor operations, patients have expired on the operating table. Even the hearty assurances of the surgeon, the anaesthetist and the nurses don’t altogether dispel or alleviate your lingering doubts. In a word, you are feeling ‘vulnerable’.

As you lie on the trolley you look upwards. Lights – usually strong lights. You wonder whether this may not be the last visual experience in your life. You have heard, too, that for those who have undergone near-death experiences one of their strongest recollections is of rushing down a long dark tunnel towards a radiant light. Will this be your next visual experience? What of the ‘thereafter’?

The Catholic Requiem Mass for the Dead reassures, responding to these doubts and fears:

In Jesus who rose from the dead our hope of resurrection dawned.

The sadness of death gives way to the bright promise of immortality.

For your faithful people life is changed, not ended.

When the body of our earthly dwelling lies in death,

We gain an everlasting dwelling-place in heaven.

‘Changed’, it says, ‘not ended’. I wonder. Eternal life for this life? Immortality for mortality? A resurrected body for this frail carcase? Spirit for matter? Everlasting happiness for the troubles of this world? Think Dante’s Paradiso, in the presence of the Beatific Vision ’The Love that moves the sun and the other stars’? Ah, yes – but there’s also Purgatorio or even Inferno!

Or reincarnation perhaps? Will I come back as a better, more successful person? Or as a cat? Or as a cockroach? The endless cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth – the phoenix rising from the ashes. Is this the ‘thereafter’?

Or is this really the END? Not ‘changed’ but ‘ended’? Definitively. Is the light towards which I rush at the end of the tunnel merely an illusion, merely the after-image of those lights that shone down from above the trolley? Nothing else but blackness? Not even blackness – nothing at all – the end of consciousness?

‘Changed’ or ‘ended’? Aye, there’s the rub. Nothing more than a memory, perhaps ‘immortalised’ (!) in prose, poetry or even on headstones? Or a change, a genuine change, like entering this life. Passing from one state of consciousness to another. Was this what Blair Trethowan meant by his work: ‘Change’? Passing from one state of consciousness to another different state of consciousness? Or was it passing from consciousness out of consciousness altogether? What was he thinking, expecting, when he was approaching death?

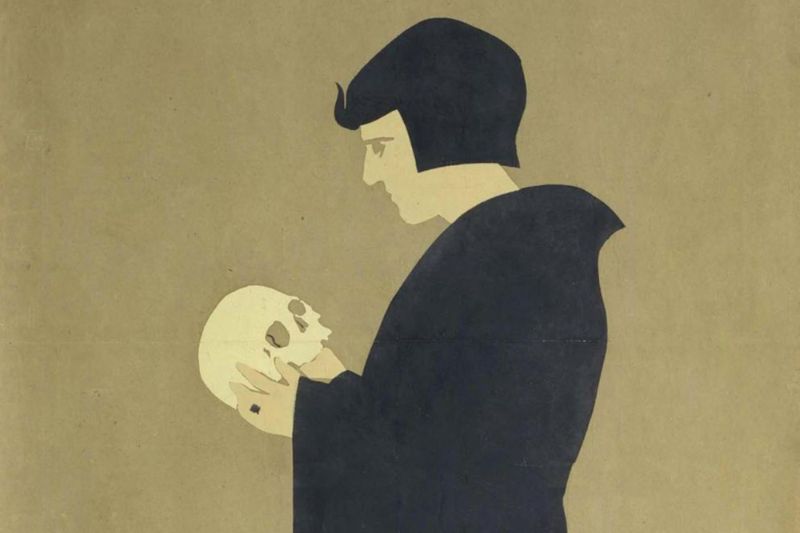

The ‘Thereafter’. Not merely wonder but fear also: ‘Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all’. Inevitably, Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes a calamity of so long life …

But that the dread of something after death

The undiscovered country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of.

Wonder? Fear? Perhaps even courage in the face of the ‘thereafter’. Not denying fear, but facing up to, accepting, even embracing, death. And death shall have no dominion. Soldiers in the trenches in the Somme in the First World War with death and the ‘thereafter’ their daily companions. A whole clutch of young war poets, both secular and Christian, many of whom perished subsequently in the conflict, celebrated this courage in the face of death and mused on the nature of the ‘thereafter’. Would such spirit pass into nothingness? Was the rhetoric of the generals, the politicians and the poets, the inscribed monuments reared in towns and villages in their memory – were all these the only ‘thereafter’, or were they merely the husks from which new life had already emerged?

So, finally, is there hope? For Christians? Even for agnostics? Everything else lives for but a brief moment and then perishes. Even the Christian Ash Wednesday, as the priest anoints the penitent with ashes: Dust thou art and unto dust thou shalt return. Why would one hope? Because, so you believe, human beings are radically different? Not like the plants, not even like the animals. That spark, that spirit, consciousness, the mind, love, sacrifice, understanding, the soul, shall all these pass into oblivion? So, in the end, is there hope? Only a forlorn hope? Or an optimistic hope? A reassuring hope? A resolute hope? A justifiable hope? Or just hope?

For Christians at least, there are precedents in which to place our hope:

In Jesus who rose from the dead our hope of resurrection dawned.

The sadness of death gives way to the bright promise of immortality.

For your faithful people life is changed, not ended.

When the body of our earthly dwelling lies in death

We gain an everlasting dwelling place in heaven.

Bill Uren, SJ, AO, is a Scholar-in-residence at Newman College at the University of Melbourne. A former Provincial Superior of the Australian and New Zealand Jesuits, he has lectured in moral philosophy and bioethics in universities in Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth and has served on the Australian Health Ethics Committee and many clinical and human research ethics committees in universities, hospitals and research centres.

Main image: Hamlet pondering Yorick's skull, Sir William Nicholson (1872-1949) (Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)