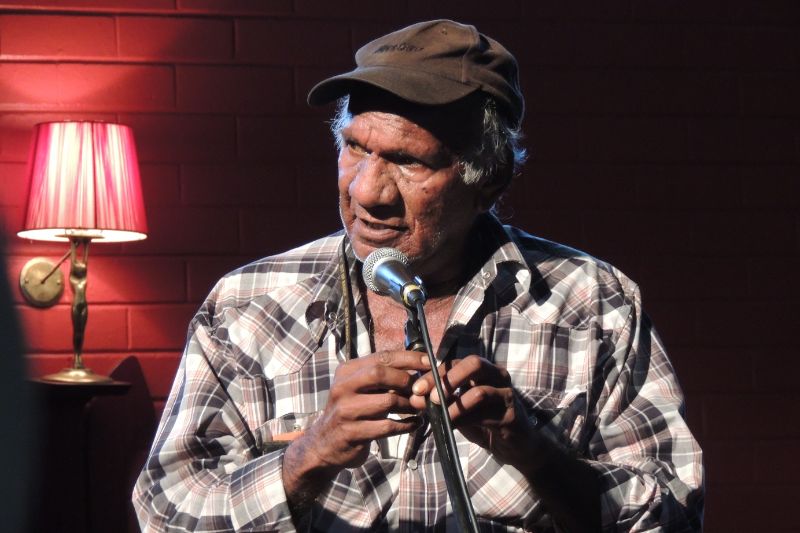

Late last month, after the November 2023 passing of a great Australian environmental warrior, commemorative gatherings celebrated his memory at both at Lake Eyre South and in Naarm/Melbourne. Neither will be the last dedicated to the memory of Uncle Kevin Buzzacott, one of our nation’s great men. He was indeed a warrior – a man of enormous courage, extraordinary imagination and strategic thinking. He was a person totally committed in love to the well-being of country and waters, for the present and especially for the future generations.

An Arabunna man, Uncle Kevin devoted himself to the protection of Lake Eyre and Wibma Mulka, the Mound Springs, and the whole of that delicate, glorious country of north eastern South Australia with its Great Artesian Basin’s ancient waters threatened by the succession of powerful mining companies operating Roxby’s Olympic Dam. The original ‘joint venturers’ were Western Mining Co (WMC) and British Petroleum (BP); then WMC; then in 2005, BHP/Billiton. From 2018, the largely foreign-owned company, BHP, is the operator.

Born on Finniss Springs Station on October 9, 1946, Uncle Kevin was always proud to declare that he ‘was born with the Old People, the old way. I was not born in a hospital. We lived in humpies then.’ After schooling years in Maree, he worked on the railways, and then did droving and station work until 1982 when, as he declared, ‘I took up the Aboriginal fight for freedom and peace.’ He worked in various drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities and in Aboriginal education at Alice Springs’ Aboriginal run Yipirinya School. He then moved on to full time volunteer environmental protection and care for country including calling his own people back ‘home.’

In the 1990s, I lived in Coober Pedy where the senior Aboriginal Women – Kungkas – intent on preserving and reviving the traditional women’s culture, formed themselves into Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta. From 1998 on, when the grave threat of the federal government’s low level and intermediate level national nuclear waste dump emerged, they became intent on the task of preserving the country of their beloved Seven Sisters’ creation, from the threat. At their first public meeting – in Melbourne at the ‘Global Survival and Indigenous Rights conference’, as their honorary ‘paper worker’, I was instructed to film Kevin Buzzacott’s address. They assured me it would be worth it.

During that spellbinding session, I became convinced I was listening to one of the nation’s great orators. And with that perfect timing of one, he broke off at one point to call up those desert women, the Kungkas, to share the outdoor stage with him, all uniting in protection of country. Uncle Kevin’s own authority was evident as an Arabunna man intimate with knowledge of, and the passion for, his country, in stark contrast to the interlopers. The need ‘to approach the country the right way’ was his constant life-long theme:

‘…In our People, everybody know who’s who, We know the country, we know everything. We know how we fit here – that’s our people.

Old People’s spirits on this land before. I can’t get away from that. I don’t want to.

Old People made us, they made this country. We’re born for that.

Our role is to look after each other. And look after this country. We’re born for that.

It’s too old.

Leave that stuff there! Don’t destroy sacred sites. We never dig that country for uranium. We’ve got the key for this country. Not them mob.

You put your foot there, put your foot there – that country know that foot.

‘Oh, that’s my kid’s foot’ – he know that. Them other mob put their foot there: ‘U’whoah! What have we got here?...’

His final cry, so often repeated before and since, was full of belief, hope and encouragement, ‘…This country is alive – it’s too magical… But if we move, that Old Country power will come with us.’

The next year, 1999, under Uncle Kevin’s leadership, many young environmentalists joined the venture he named the ‘Arabunna Going Home Camp’ set up on the shores of Lake Eyre. For these ‘Keepers of Lake Eyre’ this was arduous, patient campaigning as Uncle Kevin’s presence, courage, wisdom and cultural knowledge, love of the land and extraordinary communication skills continued to mutually sustain the more youthful energy, commitment and dedication of his companions. Uncle Kevin called twice for the Kungkas to travel the southern part of the Oodnadatta Track to become part of the camp. Once we witnessed a mystical session when, as part of his teaching, he 'became' the Lake. It was a physical suffering to him to witness the profligate exploitation of the extraordinary ancient waters of the Great Artesian Basin, including its damaging effect on the Springs. With the blessing from successive SA governments, the Roxby mine at Olympic Dam continues to extract up to 35 million litres of water a day, and at no charge.

'Kevin Buzzacott will always be known as one of Australia’s greatest leaders who led from the margins a cause he brought into centre stage of the Australian community.'

When, in 2000, Western Mining eventually sacked the Camp, rather than simply lament this cowardly action, Uncle Kevin reciprocated by strategically switching the Camp and its sacred fire to a site which would be notably more in the public view. Named 'Genocide Corner' in the Adelaide CBD, the new site was erected at no less an address than next to the entrance of Government House. With the added advantage of being directly across from Parliament House, Genocide Corner Camp, North Terrace, created a situation which caused acute embarrassment to some including the Adelaide City Council, and of course, righteous indignation to many.

Predictably, News Ltd indignantly devoted a front page with its banner headline ‘Not in Our Front Yard’ and many other aggrieved reports aimed at those who would tarnish both North Terrace respectability and the reputation of one of Australia’s largest mining companies.

Genocide Corner had to be abandoned for various reasons including because it was time to walk – yes, walk! – from Lake Eyre to Sydney in time to take advantage of the national and international media present at the 2000 Olympics. One aim of the Peace Walk was to present the case for Australia’s breaching of basic environment laws. The Kungkas and I were part of the group to see off the 50-strong entourage to literally carry the fire ‘for peace and justice.’

As Uncle Kevin explained in an interview with his long time close colleague Tanengkald lawyer, activist and academic Irene Watson: ‘The most important thing is to walk that old country; …walk in the footsteps of the old ancestors and feel the power of that old country and old spirit...’

Astoundingly, three months later the entourage had arrived after spectacular connections with many Aboriginal as well as non-Aboriginal supporters in country towns along the route.

Shortly afterwards came another Uncle Kevin invitation to the Kungkas: ‘Come to Sydney yourselves to benefit from the international media.’ Despite the many laws having been swiftly passed about what seemed to be almost infinite ways one could be arrested if protesting, this is what we did. As Emily Munyungka Austin later proudly declared, ‘We were brave women!’ We arrived in Sydney, of course by train, to find an enormous tent already set up and waiting at the Botany Bay site Uncle Kevin had named ‘Captain Cook’s Foot.’ Some international media were interested, travelling out to the site. They, especially the UK media, were astounded to learn they were in the company of nuclear survivors (as many of the Kungkas were), of the 1950s-60s British nuclear tests on their country in South Australia. Uncle Kevin’s own efforts, ignored by Australian media, featured on the front page of the Chicago Tribune.

In surely one of the most creative in all Kevin Buzzacott’s life time of creative protests, at 5am one morning, the Kungkas and I were collected from Camp to participate in the ‘Cleansing of the Harbour’ expedition. Already on the foredeck of a friend’s privately owned ferry, Uncle Kevin and Aunty Isobel Coe were surrounded by small eucalyptus branches, fuel for the small ceremonial fire. The ceremonial cleansing smoke was sent out as we cruised over the magnificent Harbour – a harbour of course completely taken over by white interests.

Having reached the Heads, we turned back with a brief stopover at maybe Rose Bay which gave waiting regular ferry passengers an opportunity to loudly voice opinions for (or against) the wisdom (or audacity) of Aboriginal people to be restoring Harbour wellbeing. The clear run back to base, was, we all noticed at different times, accompanied progressively by two state tugs and then no less than three state helicopters. ‘Looks like jail for us!‘ warned Diane, the youngest Kungka. But our ferry operator slid back home into dock with consummate skill – just in time. Of course, even this brilliant expedition pales in comparison to Uncle Kevin’s key role in participating in the much later West Papuan Freedom Flotilla of August 2013.

In December 2004, his campaign became more visible internationally with the Peace Walk from Roxby Downs to Hiroshima. The eventual Indigenous International Gathering in Japan, Uncle Kev reported, ‘was a great help‘ to his own spirit. In later years believing it was Australia’s uranium that fuelled the Fukushima reactor, Uncle Kevin formally apologised to the Japanese for his country’s role in the Fukushima catastrophe.

Kevin Buzzacott’s work was first officially recognised, overseas, with the Nuclear-Free Futures award in Ireland in 2001. Five years later, he was recognised in his own country receiving the 2006 Conservation Council of SA award and in 2007, the Australian Conservation Foundation’s Peter Rawlinson award.

Kevin Buzzacott’s brave efforts over the years included actions to effect long term change for his country, peoples, culture and cultural symbols in court against government and/or mining company actions, past, present or proposed. Appearing variously in the Magistrates court, the Federal Court, right up to the High Court of Australia, in this difficult dimension of his work he found support within the legal profession and in the Environmental Defenders Office.

Worth noting is a reference submitted at one time in his support, commending his expansive influence on young people: ‘They have learned about country, about the sacredness of the land; about Aboriginal protocol and respect including respecting the Elders; about living skills; about communication; about bush skills. Most of all they have learned about integrity, commitment and self-control. It’s been a marvellous thing for so many young people – both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal to have a personal mentor in Kevin Buzzacott.’

As news of his environmental knowledge, wisdom and powerful strategies grew, over the years Uncle Kevin was called and responded to pleas for his presence Australia wide. To cite just two, his has been a decades-long commitment to the Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra with the sacred fire. In 2006 began his active response to the call of the Melbourne Sovereignty Camp.

Integral to his commitment, Uncle Kevin was a founding member and long-term President of ANFA, Australian Nuclear-Free Alliance. Begun in 1997, ANFA is a network of Traditional Owners and other environmentalists who share a common concern about the impacts of nuclear projects, supporting each other’s work to end nuclear threats. For decades, Uncle Kevin would make the effort whenever possible, to address so many different groups of any size, including on country during the regular Friends of the Earth ‘Radioactive Tours’. In his later years, his appearance at an ANFA gathering, a rally or any type of gathering was always a bonus. In the big events like the Camp, the Walk, the overseas trips, his health crises, as well as in the events of more every day life, Uncle Kevin appreciated the unwavering support of his long time partner, Margret Gilchrist. Active right up to his passing, never giving up, Uncle Kevin was on country at Alberrie Creek and Maree for many weeks in late 2023.

As Irene Watson said, ‘Kevin Buzzacott will always be known as one of Australia’s greatest leaders who led from the margins a cause he brought into centre stage of the Australian community.’

Michele Madigan is a Sister of St Joseph who has spent over 40 years working with Aboriginal people in remote areas of SA, in Adelaide and in country SA. Her work has included advocacy and support for senior Aboriginal women of Coober Pedy in their successful 1998-2004 campaign against the proposed national radioactive dump.

Main image: Kevin Buzzacott. (WikiCommons)