It started with the intention of swift victory, touted as a ‘special operation’ by the Kremlin, justified by Russian President Vladimir Putin historically and politically as necessary for his country’s security. In the two years since Russia invaded Ukraine, an estimated half-a-million are dead, a generation has been traumatised, and a halt to hostilities remains out of reach.

As things stand, the bill for Ukraine’s recovery, according to a joint assessment by the EU, World Bank and the UN, stands at US$481 billion, an increase of $75 billion from last year. As Stefan Wolff of University of Birmingham writes, an increasingly fractious globe (the conflicts in Gaza, Sudan, and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo; North Korean nuclear threats; Iran’s destabilising role in funding proxy militant groups) makes Ukraine ‘a major and increasingly costly distraction.’

The elephant in the room remains the unresolved historical problems raised by the conflict. Russian brutality and Ukrainian bravery are ill-serving descriptions, suggesting simplistic fault lines of culpability and guilt. While the Russian invasion can be said to be a violation of the UN Charter, a crime against peace, it also took place in the context of various provocations made against Moscow from the United States, notably on the issue of admitting countries formerly in the Soviet orbit to NATO.

In October 1990, the US State Department opined that ‘it is not in the best interest of NATO or the US that these states be granted full NATO membership’, warning against ‘an anti-Soviet coalition whose frontier is the Soviet border.’

To that end, one tends to forget that the invasion of February 2022 was the culmination of an ongoing conflict that had begun in 2014, involving a number of local and international factors. In his Foreign Affairs assessment on the outbreak of hostilities that year, the US political scientist John Mearsheimer wrote that the ‘US and European leaders blundered in attempting to turn Ukraine into a Western stronghold on Russia’s border.’ There were notably disruptive roles played by then US Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian affairs, Victoria Nuland, who revealed in 2013 how the US had invested more than US$5 billion since 1991 to help Ukraine achieve ‘the future it deserves.’ This involved spearheading efforts of the National Endowment for Democracy.

As Russian tanks moved into Ukraine on 24 February, 2022, Mearsheimer remained convinced by his assessment: Russia had been needlessly provoked into ‘a preventive war’. While not permissible in just war theory, the Kremlin ‘certainly saw the invasion as “just”, because they were convinced that Ukraine joining NATO was an existential threat that had to be eliminated.’

One hardly has to agree with the entirety of Mearsheimer’s premise to appreciate the broader picture of provocation posed by this assessment. In September last year, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg made a candid admission at the joint meeting of the European Parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET) and the Subcommittee on Security and Defence (SEDE). That admission concerned Putin’s unequivocal intentions to invade Ukraine if NATO were to be further enlarged: ‘The background was that President Putin declared in the autumn of 2021, and actually sent a draft treaty that they wanted NATO to sign, to promise no more NATO enlargement. That was what he sent us. And was a pre-condition to not invade Ukraine. Of course, we didn’t sign that.’

'The unpalatable reality to this conflict is that some diplomatic solution will have to be found in this war of murderous attrition. Far from not having a foothold in Ukraine, the Russian imprint is bloodily large and ominous.'

In NATO’s refusal to accept Putin’s terms, including the partial dismantling of the alliance’s architecture, and the introduction of ‘some kind of B, or second-class membership’, the Russian leader ‘went to war to prevent NATO, more NATO, close to his borders.’

Prospects of a Ukrainian victory, egged on by a diminishing number of advocates, are becoming slim. Predictions about Russian collapse have also not eventuated. Putin remains in power. His opponents remain in mortal danger. Challengers and potential usurpers are dispatched, be they mercenary chieftains such as the former Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin or political contenders like Alexei Navalny. The economy has been battered by a thick battery of sanctions, but Moscow has found new markets in an increasingly fragmented trade and financial system that eschews moral principle in favour of pragmatism.

The great challenge facing Ukraine and its President Volodymyr Zelensky on the occasion of the anniversary is a flagging appetite for aid in various capitals, despite the lip service being paid to his efforts by the leaders of Canada, Belgium, Italy and the EU chief, Ursula von der Leyen on a visit to Kyiv. At the Munich Security Conference held on 17 February, Zelensky blamed the loss of Avdiivka to acute military shortages arising from inadequate assistance.

In Washington, support for Ukraine’s war effort has well and truly lost its lustre and relevance, notably in Republican circles. In Congress, the GOP has been obstructing further military assistance to Kyiv. In the grave words of Republican Senator Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, ‘I don’t like this reality.’ Putin was ‘an evil war criminal’ but he would ‘not lose this war.’ On the battlefield, Ukrainian soldiers, in the aftermath of their defeat at Avdiivka, again face critical challenges in terms of casualties and war material.

The Ukrainian president continues to hope that the rhetoric of noble warriors battling satanic marauders will translate into concrete support. ‘When our soldiers destroyed the Russian killers’ landing and didn’t allow Russia to create a foothold here, the world saw the most important thing,’ he declared. ‘It saw that any evil can be defeated, and Russian aggression is no exception.’

The unpalatable reality to this conflict is that some diplomatic solution will have to be found in this war of murderous attrition. Far from not having a foothold in Ukraine, the Russian imprint is bloodily large and ominous. It is hard to see how Kyiv can avoid making some territorial and political concessions. Until Russia is captured by the dove of peace, and Ukraine finds itself short of options, the warring deities will continue to be in the ascendancy, leaving their sorrowful carnage in their wake.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University.

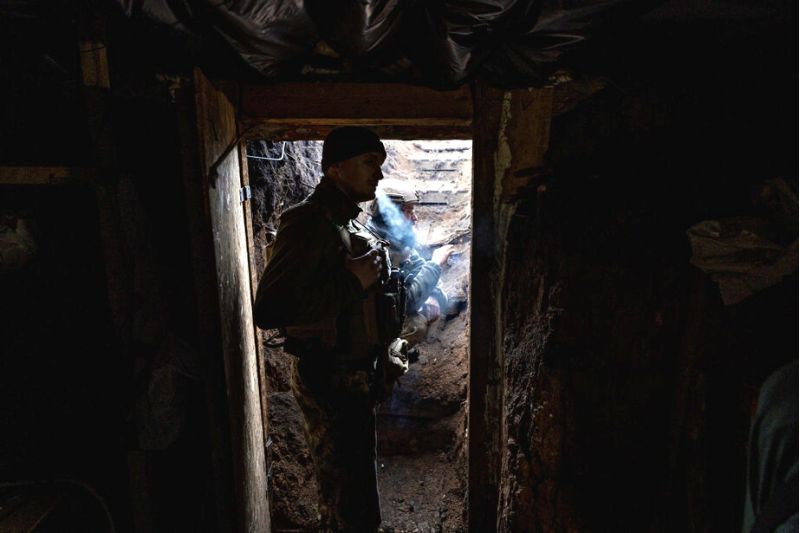

Main image: Soldiers in Bakhmut from a Ukrainian assault brigade smoke at the entrance to a bunker while waiting for orders (John Moore/Getty Images)