It's a great honour to deliver this 43rd Barry Marshall Lecture. I never knew Barry. He died at Oxford in 1970 when I was finishing school in Toowoomba. I crossed his paths a couple of times, and much after his time, in later years. I commenced my theology studies here at the United Faculty of Theology on the College Crescent in 1979. Barry was chaplain here at Trinity from 1961-1969. Armed with an Oxford doctorate, he had returned to Australia as a member of the Brotherhood of the Good Shepherd in 1956, two years after I was born, to be priest in charge out at Bourke of all places. I well recall my experience at Engonia near Bourke during the 1997 Wik debate. I had been flying around western Queensland and western New South Wales meeting with angry pastoralists who were convinced that they were going to lose their land and that their families would not be safe with native titleholders having ready access to their properties. I arrived late for a meeting. You could cut the air with a knife. I walked into a room to be told, 'You should get back to your presbytery and say your prayers.' I was grateful for the observation, offering only two in response: I believed in the power of prayer but I did not think Wik could be solved by prayer alone; and I did not think it could be solved just by Aborigines, miners and pastoralists getting together – there might just be a place for the occasional honest broker or independent thinker. I would offer the same observations in relation to the issue of asylum seekers which is presently confounding the nation.

I was delighted to learn that the gracious entry on Barry Marshall in the Australian Dictionary of Biography was done by Dr John Morgan who lived here at Trinity and taught me sociology of religion back in the 80s. He was ably assisted with the entry by Robin Sharwood one time Warden here at Trinity and who had long been a fine Anglican presence around Melbourne legal circles when I was the first Jesuit to read at the Melbourne Bar in the late 70s.

Armed with my legal and theological training received around this College Crescent, I happily honour Barry Marshall who 'was renowned for his energy, as well as for his clever, and at times sharp, wit; his preaching always engaging, reveal(ing) a legacy of metaphysical insight' by taking up Kevin Rudd's challenge issued to all of us when he spoke to Lisa Wilkinson on the Today program on 25 July 2013:

The challenge that I put out to anyone who asks that we should consider a different approach is this: what would you do to stop thousands of people, including children, drowning offshore, other than undertake a policy direction like this? What is the alternative answer?

In this lecture, I will make the case in the medium to long term for the negotiation of a regional agreement involving at least Australia, Indonesia and Malaysia. Such an agreement could assist with stopping the boats as well as contributing to enhanced upstream processing and protection of asylum seekers. I will concede that such an agreement could not be negotiated quickly and thus other measures would be required if we were to stop the boats promptly. Given the blow-out in arrivals, I concede the need for arresting the number of boats and asylum seekers arriving in Australia. If shock and awe measures are to be adopted by our elected leaders, they should put to rest their differences over means, and they should adopt shock and awe measures only once they have done their homework, minimising the prospect of damage and always maintaining responsibility for unaccompanied minors and other vulnerable persons who have reached Australia.

First world countries wanting to stop the boats lawfully and ethically

The issue which confounds us tonight is working out what's ethical and what works when confronting an escalating flow of asylum seekers coming to our shores by boat without visas and risking their lives on perilous voyages. First world countries with maritime borders have been wrestling with this issue now for over thirty years. And churches in these first world countries have been wrestling with the gospel imperatives of justice and compassion expressed in the parables of Jesus like the Good Samaritan.

There is much confusion about the ethical and legal considerations which apply when asylum seekers present at the borders of first world countries. For example the website of the Refugee Council of Australia asserts: 'The UN Refugee Convention (to which Australia is a signatory) recognises that refugees have a right to enter a country for the purposes of seeking asylum, regardless of how they arrive or whether they hold valid travel or identity documents.' The Australian Government website states: 'International law recognises that people at risk of persecution have a legal right to flee their country and seek refuge elsewhere, but does not give them a right to enter a country of which they are not a national. Nor do people at risk of persecution have a right to choose their preferred country of protection.'

On 29 September 1981, US President Ronald Reagan, frustrated by the flow of asylum seekers across the sea from Haiti, signed Executive Order 12324 on the 'Interdiction of Illegal Aliens'. Reagan characterised 'the continuing illegal migration by sea of large numbers of undocumented aliens into the southeastern United States' as 'a serious national problem detrimental to the interests of the United States.'

The Oxford don and guru of the international jurisprudence on refugee issues Guy Goodwin-Gill has opined that this Order became 'the model, perhaps, for all that has followed'. Following the military coup in Haiti in 1991, repatriations were suspended for 6 weeks. Then in May 1992, 'President (George) Bush decided to continue interdiction and repatriation, but without the possibility of screening-in for those who might qualify as refugees'. When inaugurated as President in January 1993, Bill Clinton maintained the interdiction practice, putting paid to the claim that this was just the initiative of the Republicans. It turned out that both major political parties were committed to stopping the boats, doing whatever it takes. Sound familiar? The US Supreme Court described the matter thus:

With both the facilities at Guantanamo and available Coast Guard cutters saturated, and with the number of Haitian emigrants in unseaworthy craft increasing (many had drowned as they attempted the trip to Florida), the Government could no longer both protect our borders and offer the Haitians even a modified screening process. It had to choose between allowing Haitians into the United States for the screening process or repatriating them without giving them any opportunity to establish their qualifications as refugees. In the judgment of the President's advisers, the first choice not only would have defeated the original purpose of the program (controlling illegal immigration), but also would have impeded diplomatic efforts to restore democratic government in Haiti and would have posed a life-threatening danger to thousands of persons embarking on long voyages in dangerous craft. The second choice would have advanced those policies but deprived the fleeing Haitians of any screening process at a time when a significant minority of them were being screened in.

On May 23, 1992, President Bush adopted the second choice. After assuming office, President Clinton decided not to modify that order; it remains in effect today. The wisdom of the policy choices made by Presidents Reagan, Bush, and Clinton is not a matter for our consideration.

It took 15 months of concerted advocacy from human rights advocates to convince Clinton to institute refugee status determination interviews on board ship. In Sale v Haitian Centers Council, Inc, the US Supreme Court ruled that these harsh presidential practices were valid. Justice Stevens delivering the opinion of the Court said: 'The President has directed the Coast Guard to intercept vessels illegally transporting passengers from Haiti to the United States and to return those passengers to Haiti without first determining whether they may qualify as refugees. The question presented in this case is whether such forced repatriation, "authorized to be undertaken only beyond the territorial sea of the United States," violates … the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 . We hold that neither (the Act) nor Article 33 of the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees applies to action taken by the Coast Guard on the high seas.' In relation to Article 33 of the Refugees Convention, the Supreme Court said:

The drafters of the Convention and the parties to the Protocol may not have contemplated that any nation would gather fleeing refugees and return them to the one country they had desperately sought to escape; such actions may even violate the spirit of Article 33; but a treaty cannot impose uncontemplated extraterritorial obligations on those who ratify it through no more than its general humanitarian intent. Because the text of Article 33 cannot reasonably be read to say anything at all about a nation's actions toward aliens outside its own territory, it does not prohibit such actions.

In an uncharacteristic mode for the usually isolationist US judges, the Supreme Court in footnotes quoted many international law scholars including Guy Goodwin-Gill who had written: 'A categorical refusal of disembarkation cannot be equated with breach of the principle of non-refoulement, even though it may result in serious consequences for asylum-seekers'. They also quoted A. Grahl-Madsen who wrote: '[Non-refoulement] may only be invoked in respect of persons who are already present—lawfully or unlawfully—in the territory of a Contracting State. Article 33 only prohibits the expulsion or return (refoulement) of refugees to territories where they are likely to suffer persecution; it does not obligate the Contracting State to admit any person who has not already set foot on their respective territories'.

The US approach has given licence these last two decades to other first world countries worried about an influx of boat people. In Europe, the focus has been on the Mediterranean Sea. The European Court of Human Rights became apprised of the EU practices in the Mediterranean in the 2012 case of Hirsi v Italy.

The applicants in that case were eleven Somali nationals and thirteen Eritrean nationals who were part of a group of about two hundred individuals who left Libya aboard three vessels with the aim of reaching the Italian coast. On 6 May 2009, when the vessels were 35 nautical miles south of the island of Lampedusa, they were intercepted by three ships from the Italian Revenue Police and the Coastguard. The occupants of the intercepted vessels were transferred onto Italian military ships and returned to Tripoli. On arrival in the Port of Tripoli, the migrants were handed over to the Libyan authorities. According to the applicants' version of events, they objected to being handed over to the Libyan authorities but were forced to leave the Italian ships. At a press conference held on 7 May 2009 the Italian Minister of the Interior stated that the operation to intercept the vessels on the high seas and to push the migrants back to Libya was the consequence of the entry into force on 4 February 2009 of bilateral agreements concluded with Libya, and represented an important turning point in the fight against clandestine immigration. The applicants complained that they had been exposed to the risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment in Libya and in their respective countries of origin as a result of having been returned. They relied on Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights which provides: 'No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.'

The Court said:

The Court has already had occasion to note that the States which form the external borders of the European Union are currently experiencing considerable difficulties in coping with the increasing influx of migrants and asylum seekers. It does not underestimate the burden and pressure this situation places on the States concerned, which are all the greater in the present context of economic crisis. It is particularly aware of the difficulties related to the phenomenon of migration by sea, involving for States additional complications in controlling the borders in southern Europe. However, having regard to the absolute character of the rights secured by Article 3, that cannot absolve a State of its obligations under that provision. The Court reiterates that protection against the treatment prohibited by Article 3 imposes on States the obligation not to remove any person who, in the receiving country, would run the real risk of being subjected to such treatment.

The Court ruled unanimously that the applicants were within the jurisdiction of Italy for the purposes of Article 1 of the Convention; that there had been a violation of Article 3 of the Convention on account of the fact that the applicants were exposed to the risk of being subjected to ill-treatment in Libya; and that there had been a violation of Article 3 of the Convention on account of the fact that the applicants were exposed to the risk of being repatriated to Somalia and Eritrea.

Lampedusa continues to be a beacon for asylum seekers fleeing desperate situations in Africa seeking admission into the EU. Lampedusa is a lightning rod for European concerns about the security of borders in an increasingly globalized world where people as well as capital flow across porous borders. That's why Pope Francis went there on his first official papal visit outside Rome. At Lampedusa on 8 July 2013, Pope Francis said:

"Where is your brother?" Who is responsible for this blood? In Spanish literature we have a comedy of Lope de Vega which tells how the people of the town of Fuente Ovejuna kill their governor because he is a tyrant. They do it in such a way that no one knows who the actual killer is. So when the royal judge asks: "Who killed the governor?", they all reply: "Fuente Ovejuna, sir". Everybody and nobody! Today too, the question has to be asked: Who is responsible for the blood of these brothers and sisters of ours? Nobody! That is our answer: It isn't me; I don't have anything to do with it; it must be someone else, but certainly not me. Yet God is asking each of us: "Where is the blood of your brother which cries out to me?" Today no one in our world feels responsible; we have lost a sense of responsibility for our brothers and sisters. We have fallen into the hypocrisy of the priest and the levite whom Jesus described in the parable of the Good Samaritan: we see our brother half dead on the side of the road, and perhaps we say to ourselves: "poor soul…!", and then go on our way. It's not our responsibility, and with that we feel reassured, assuaged. The culture of comfort, which makes us think only of ourselves, makes us insensitive to the cries of other people, makes us live in soap bubbles which, however lovely, are insubstantial; they offer a fleeting and empty illusion which results in indifference to others; indeed, it even leads to the globalization of indifference. In this globalized world, we have fallen into globalized indifference. We have become used to the suffering of others: it doesn't affect me; it doesn't concern me; it's none of my business!

Here we can think of Manzoni's character – 'the Unnamed'. The globalization of indifference makes us all 'unnamed', responsible, yet nameless and faceless.

The Australian challenge

Here in Australia, all major political parties are now committed to stopping the boats heading for Christmas Island. They are prepared to do whatever it takes – or almost. Being in election mode, they are not willing to embrace each other's options. Each thinks there is still electoral advantage in avoiding bipartisan support for the means even though there be furious agreement about the end to be achieved. We could spend this whole lecture analyzing the political motivations of Labor's criticisms of John Howard's Pacific Solution and the Coalition's criticism of Julia Gillard's Malaysia Solution. Suffice to say that the following exchange on the ABC Q&A a week ago (including Doug Cameron's slip of the tongue) marks a turning point in our nation's political history in dealing with asylum issues:

DOUG CAMERON: Yeah. Look, I think that the government has and Prime Minister Howard - Prime Minister Rudd has indicated - well, I'll go back to Howard because ...

GREG HUNT: Gillard?

DOUG CAMERON: No, because - you know, John Howard was operating in a completely different atmosphere, a completely different situation.

GREG HUNT: He created that situation.

DOUG CAMERON: Things change. He didn't create that situation. The situation...

GREG HUNT: He created and defined the circumstances.

TONY JONES: Hold on a sec. We've got to let him answer.

DOUG CAMERON: The situation at the time was conducive to making sure boats stop. That's the international situation. It is changed. You have got international people smugglers. They are all over the world now putting people through in Australia and that's the big problem and we've got to try and deal with it..

TONY JONES: All right, Grahame, briefly.

GRAHAME MORRIS: I used to think that Doug was roughly where the heart and soul of the Labor Party was but what he just said is essentially what John Howard would say and you wonder where is the heart and the soul of the Labor Party now?

Having announced his own Pacific Solution on 19 July 2013, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd speaking on the Today show with Lisa Wilkinson said the issue was deaths at sea and the increasing numbers which were swamping the humanitarian migration category. He put out this challenge, presumably to the Churches, as well as all the other do gooders in the community:

I think you heard a people smuggler interviewed by a media outlet the other day say that this was a fundamental assault on their business model. Well, that's a pretty gruesome way for him to put that, but the bottom line is this, I challenge anyone else looking at this policy challenge for Australia to deliver a credible alternative policy.

In the medium term, I think the only way to stop the boats ethically is to negotiate a regional agreement with Indonesia and Malaysia. I admit that this would take a considerable period of time, a good cheque book, and a strong commitment to detailed backroom diplomatic work avoiding the megaphone diplomacy which has marked this issue of late. In the short term, the boats can only be stopped with some sort of 'shock and awe' campaign. Could such a campaign ever be ethically justified? I think there are some useful parallels in ethical discourse about the use of nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence, and about the justification, if any, for the use of torture.

The American philosopher Michael Walzer has been a long time critic of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his classic Just and Unjust Wars, he states, 'Our purpose, then, was not to avert a "butchery" that someone else was threatening, but one that we were threatening, and had already begun to carry out.' He rightly distinguishes Japan from Germany and argues that there was no need to demand unconditional surrender. '[A]ll that was morally required was that they be defeated, not that they be conquered and totally overthrown.' Walzer claims, 'In the summer of 1945, the victorious Americans owed the Japanese people an experiment in negotiation.'

In his 2007 essay 'Terrorism and Just War' Walzer writes: 'Consider the American use of nuclear weapons against Japan in 1945: this was surely an act of terrorism; innocent men and women were killed in order to spread fear across a nation and force the surrender of its government. And this action went along with a demand for unconditional surrender, which is one of the forms that tyranny takes in wartime….There can't be any doubt that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki implied, at the moment the bombs were dropped, a radical devaluation of Japanese lives and a generalised threat to the Japanese people.'

Walzer is not one of those thinkers who yields to popular sentiment in recasting the balance between principle and pragmatism. And yet it was he who 40 years ago wrote the famous essay on 'The Problem of Dirty Hands' in which he posited the moral paradox of the ticking bomb. A suspected terrorist is being held and the state officials assure the president that the terrorist has information about bombs which have been planted in schools and apartment buildings. Should he authorise the use of torture?

This essay has come into vogue since the discussion of the torture memos from the Bush administration. When interviewed in 2006, Walzer said 'we should want leaders who were prepared both to give the order and to bear the guilt'. He is not so keen on Alan Dershowitz's approach of drawing up rules for the authorisation of torture with judicial warrant that the rules have been complied with. Walzer thinks extreme cases make bad law. He says:

I don't want to rewrite the rule against torture to incorporate this exception. Rules are rules, and exceptions are exceptions. I want political leaders to accept the rule, to understand its reasons, even to internalise it. I also want them to be smart enough to know when to break it. And finally, because they believe in the rule, I want them to feel guilty about breaking it – which is the only guarantee they can offer us that they won't break it too often.

When confronted with any of these truly awful moral dilemmas, whether as private citizens or as politicians, we seek the prophetic voice and principled discussion before taking pragmatic action. We can heed John Henry Newman's advice:

I should look to see what theologians could do for me, what the Bishops and clergy around me, what my confessor; what friends whom I have revered: and if, after all, I could not take their view of the matter, then I must rule myself by my own judgment and my own conscience.

And so it must be for Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott when they sit in the isolation of their own studies contemplating whether “shock and awe” is justified to stop the boats.

This advice is consistent with the Second Vatican Council's injunction to the laity in Gaudium et Spes:

Lay persons should also know that it is generally the function of their well-formed Christian conscience to see that the divine law is inscribed in the life of the earthly city; from priests they may look for spiritual light and nourishment. Let lay persons not imagine that their pastors are always such experts, that to every problem which arises, however complicated, they can readily give a concrete solution, or even that such is their mission. Rather, enlightened by Christian wisdom and giving close attention to the teaching authority of the Church, let the laity take on their own distinctive role.

Preparing this lecture, I looked backed to my 2002 Anglicare Tasmania Social Justice Lecture entitled Tampering with Asylum: Recent Developments in the Treatment of Asylum Seekers in Australia which I delivered just after John Howard had successfully implemented his Pacific Solution Mark I stopping the boats with, in hindsight, more bluff than actual shock and awe. I referred to Luke 16:26:

Abraham said, “Remember, my child, that all the good things fell to you while you were alive, and all the bad to Lazarus; now he has his consolation here and it is you who are in agony. But that is not all: there is a great chasm fixed between us; no one from our side who wants to reach you can cross it, and none may pass from your side to us.”

If seeking to implement a Christian Response to refugees and asylum seekers on our doorstep, I said we might contemplate the present Australian version of the parable of Dives and Lazarus: (Lk 16:19-26 with a contemporary Australian gloss)

There was once a rich man, who dressed in purple and the finest linen, and feasted in great magnificence every day. At his gate covered with sores, lay a poor man named Lazarus, who would have been glad to satisfy his hunger with the scraps from the rich man's table. Even the dogs used to come and lick his sores. One day the poor man died and was carried away by the angels to be with Abraham. The rich man also died and was buried, and in Hades, where he was in torment, he looked up; and there, far away was Abraham with Lazarus beside him. “Abraham, my father,” he called out, “Take pity on me! Send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water to cool my tongue, for I am in agony in this fire. And remember that I overlooked Lazarus at my door only because there were many other people on the other side of the world who were in even greater need. I wanted to dispense charity and justice in an orderly way, not rewarding queue jumpers like Lazarus who is now with you.” But Abraham said, “Remember, my child, that all the good things fell to you while you were alive, and all the bad to Lazarus; now he has his consolation here and it is you who are in agony. But that is not all: there is a great chasm fixed between us; no one from our side who wants to reach you can cross it, and none may pass from your side to us.”

Eleven years ago, I proposed three simple questions, and I propose them again this evening with a slight variation to the third: Given that Australia has the advantage of geographic isolation, I ask my government, why don't we try to be just a little more decent rather than less decent than other countries with the same living standards when it comes to our treatment of those who arrive (whether with or without a visa) invoking our protection obligations? Or if that is judged too naïve, how about we aim to be just as decent as those who receive ten times more asylum seekers than we do? Or if that is too much to ask (given the fear driven mandate of the 2001 election and the mantras of the 2013 election), how about we limit our indecency to our treatment of adults, ensuring that never again are kids (used as part of the government battle plan)? In 2002, I said, 'It is in the interests of the refugees of the world that we address the problems of secondary movement and 9-11 heeding the warning of Mr Lubbers (then head of UNHCR) that we “build an effective system of international burden sharing, where governments are discouraged from taking unilateral and punitive action, and where refugees are able to rely on adequate protection and assistance within their regions of origin. For to take punitive action is to shoot oneself in the foot. It is not effective, and it only worsens the climate between North and South".'

Knowing that a future Abbott government would be very punitive in its treatment of boatpeople and suspecting that Labor would try to match its opponents in this forthcoming election, I attempted to outline a proposal for the medium term aimed at stopping the boats during the next Australian Parliament when I spoke at the National Asylum Summit on 27 June 2013, the morning after Kevin Rudd was re-elected leader of the Labor Party and Prime Minister. I was responding to Jeff Crisp, the Head of the Policy Division and Evaluation Service of UNHCR in Geneva. With a refreshingly international and humanitarian lens, Jeff raised three questions:

- Why has the enforcement and deterrence agenda become so dominant?

- What have been the consequences of that agenda for refugee protection?

- Can alternative (and better) approaches be found?

In my response to these questions, I said I wanted to apply 'a national Australian political lens as we all stare down the barrel of a new government likely to be elected in two months time with a commitment and a mandate to stop the boats which are arriving in numbers we Australians have not known before.' This is what I said. It was not well received by many other refugee advocates. Six weeks on and in the wake of the Rudd PNG-Nauru Solution, I don't know that I would change a word of it.

A medium term solution to stopping the boats

Pragmatically, and with only limited time, I want to outline the contours for a better approach here in Australia – better than committing to forcibly turning around boats on the high seas, à la Abbott, and better than transporting people to Nauru and Manus Island for processing or to Malaysia to join an asylum queue of 100,000 or permitting people to reside in the Australian community but without work rights and with inadequate welfare provision under the rubric of a 'no advantage' test, à la Gillard. Outlining these contours, I want to defend the Refugee Convention and urge that Australian political leaders of every ilk maintain a commitment both to the Convention and to onshore processing with minimal detention and adequate rights to work and welfare while awaiting processing in the community. Hopefully any changes adopted can be worked against a backdrop of our providing at least 20,000 humanitarian places a year in our migration program, 12,000 of those being for refugees.

We must abandon the ill-defined, unworkable 'no advantage test'. The all-party Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights this month noted:

The government has been unable to provide any details as to how the "no advantage" policy will operate in practice. It remains a vague and ill-defined principle that risks creating a complex framework with insufficient transparency. It has resulted in a confusing array of measures focused not so much on the status of the person as their mode and date of arrival in Australia.

The committee is concerned about the practical consequence of the application of the "no advantage principle", which would appear to be either a deliberate slowing down of processing applications for refugee status or deliberate delays in resettlement once a person has been determined to qualify as a refugee, inconsistent with the prohibition against arbitrary detention in article 9 of the ICCPR. In this respect the committee notes that as of late May 2013, some nine months after the adoption of the policy, processing of the claims of those who arrived by boat has not commenced in Australia or PNG and that there have been only preliminary interviews of some of those who have been transferred to Nauru. A failure to put in place such procedures for persons held in detention for such periods appears to the committee to constitute arbitrary detention of those who have been held for an extended period.

Given leadership tensions in the Government, Caucus found itself this week unable to debate the 'no advantage' test even though it has been so comprehensively discredited by an all party committee of the Parliament without any dissent from government members. The test is incoherent, unworkable and unAustralian. It's not a test at all; it's not a principle; it's not a policy; it's a slogan as unhelpful as 'Stop the boats'.

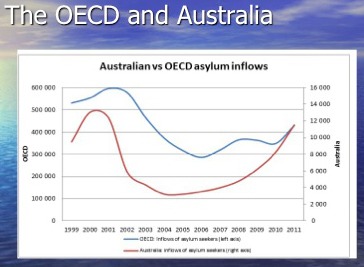

Jeff Crisp's graph of 'Australia vs OECD asylum inflows' you will have noted cuts out at 2011. The rate of boat arrivals has escalated to Australia since then. The red line is now well off the graph. In this financial year, '25,145 people have arrived on 394 boats - an average of over 70 people and more than a boat a day' as Scott Morrison, Tony Abbott's Shadow Minister never tires of telling us. Except for Sri Lankans, most of those arriving by boat come not directly from their country of persecution but via various countries with Indonesia being their penultimate stop. There is an understandable bipartisan concern in the Australian parliament about the blowout of boat arrivals to 3,300 per month. An arrival rate of that sort (40,000 pa) puts at risk the whole offshore humanitarian program and distorts the migration and family reunion program. Thus the need to ensure that those risking the perilous sea voyage are in direct flight from persecution being unable to avail themselves of adequate protection or processing en route in Indonesia. If they were able to avail themselves such services in Indonesia, the Australian government would be entitled to set up disincentives and to return them safely to Indonesia. If that number were in direct flight from persecution, the Australian government would be justified in setting up measures providing only temporary protection and denying family reunion other than on terms enjoyed by other migrants. But I don't think that would be necessary. It should be a matter not of taking the sugar off the table but of trying to put the sugar out of reach except to those in direct flight from persecution, and leaving the sugar available to those who manage to reach the table whether by plane or boat, with or without a visa. And that's because there is always sugar on Australian tables no matter who is sitting with us. And so it should remain. I have never understood why the less than honest asylum seeker arriving by plane, having sought a visa not for asylum but for tourism or business, should be given preferential treatment over the honest asylum seeker arriving by boat who says, 'I am here to seek asylum.'

Jeff Crisp's graph of 'Australia vs OECD asylum inflows' you will have noted cuts out at 2011. The rate of boat arrivals has escalated to Australia since then. The red line is now well off the graph. In this financial year, '25,145 people have arrived on 394 boats - an average of over 70 people and more than a boat a day' as Scott Morrison, Tony Abbott's Shadow Minister never tires of telling us. Except for Sri Lankans, most of those arriving by boat come not directly from their country of persecution but via various countries with Indonesia being their penultimate stop. There is an understandable bipartisan concern in the Australian parliament about the blowout of boat arrivals to 3,300 per month. An arrival rate of that sort (40,000 pa) puts at risk the whole offshore humanitarian program and distorts the migration and family reunion program. Thus the need to ensure that those risking the perilous sea voyage are in direct flight from persecution being unable to avail themselves of adequate protection or processing en route in Indonesia. If they were able to avail themselves such services in Indonesia, the Australian government would be entitled to set up disincentives and to return them safely to Indonesia. If that number were in direct flight from persecution, the Australian government would be justified in setting up measures providing only temporary protection and denying family reunion other than on terms enjoyed by other migrants. But I don't think that would be necessary. It should be a matter not of taking the sugar off the table but of trying to put the sugar out of reach except to those in direct flight from persecution, and leaving the sugar available to those who manage to reach the table whether by plane or boat, with or without a visa. And that's because there is always sugar on Australian tables no matter who is sitting with us. And so it should remain. I have never understood why the less than honest asylum seeker arriving by plane, having sought a visa not for asylum but for tourism or business, should be given preferential treatment over the honest asylum seeker arriving by boat who says, 'I am here to seek asylum.'

First a little history.

At a 1938 conference in Switzerland, T. W. White, the Australian delegate, misjudged his present and future audience when he said that it would 'no doubt be appreciated that as we have no racial problem we are not desirous of importing one'. When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was being drafted after World War II, Australia was one of the countries that was very testy about recognising any general 'right of asylum' for refugees. Australia conceded that a person had the right to live in their country; they had a right to leave their country; they had a right not to be returned to their country if they were in another country and if they feared persecution on return to their own country. But, Australia believed, people did not have the right to enter another country without invitation, having exercised the right to leave their own country, even if they feared persecution. In 1948 the drafters of the universal declaration proposed that a person have the right to be 'granted asylum'. Australia was one of the strong opponents, being prepared to acknowledge only the individual's right 'to seek and enjoy asylum', because such a right would not include the right to enter another country and it would not create a duty for a country to permit entry by the asylum seeker.

During the preparations for the 1948 discussions, Tasman Heyes, Secretary of the Department of Immigration wrote:

If it is intended to mean that any person or body of persons who may suffer persecution in a particular country shall have the right to enter another country irrespective of their suitability as settlers in the second country this would not be acceptable to Australia as it would be tantamount to the abandonment of the right which every sovereign state possesses to determine the composition of its own population, and who shall be admitted to its territories.

John Howard was not the first Australian to proclaim that the Australian government would decide who comes here. Australia was on the winning side of the pre-Convention argument and was able to live with Article 14 of the Declaration of Human Rights — that 'Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.' You could ask for asylum. You were not guaranteed a favourable answer, but if you received an invitation to enter, you then had the right to enjoy your asylum. The matter returned to the United Nations' agenda with the drafting of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Australian government's 1955 Brief in preparation for the General Assembly pointed out that the Department of Immigration thought 'any limitation of the right to exclude undesirable immigrants or visitors unacceptable'. In 1960 the Russians proposed a general right of asylum. Australia maintained its resistance. No right of asylum was included in the covenant.

Now let's consider the letter and spirit of the Refugee Convention.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees does not confer a right on asylum seekers to enter the country of their choice or to choose the country which is to process their refugee claim. In fact it does not confer a right to enter any country. The primary obligations in the Convention when considering proposals for border protection and orderly migration are contained in Articles 31 and 33.

#31: The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of article 1, enter or are present in their territory without authorization, provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.

#33: No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

So a refugee or asylum seeker may be illegally present or may have entered the country illegally. The issue is whether the government may impose any penalty for the illegal entry or presence for which the refugee or asylum seeker is required to show good cause.

Australian governments (of both persuasions) have long held the defensible view: 'The condition that refugees must be "coming directly" from a territory where they are threatened with persecution constitutes a real limit on the obligation of States to exempt illegal entrants from penalty. In the Australian Government's view, a person in respect of whom Australia owes protection will fall outside the scope of Article 31(1) if he or she spent more than a short period of time in a third country whilst travelling between the country of persecution and Australia, and settled there in safety or was otherwise accorded protection, or there was no good reason why they could not have sought and obtained protection there.'

The right to 'seek and enjoy asylum' in the UDHR must be understood as purely permissive. As noted by Justice Gummow of the High Court in Ibrahim, '[The] right "to seek" asylum [in the UDHR] was not accompanied by any assurance that the quest would be successful. A deliberate choice was made not to make a significant innovation in international law which would have amounted to a limitation upon the absolute right of member States to regulate immigration by conferring privileges upon individuals … Nor was the matter taken any further by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights … Article 12 of the ICCPR stipulates freedom to leave any country and forbids arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter one's own country; but the ICCPR does not provide for any right of entry to seek asylum and the omission was deliberate.'

Like all other countries, we are rightly obliged not to peremptorily expel those persons arriving on our shores, legally or illegally, in direct flight from persecution. We are entitled to return safely to Indonesia persons who, when departing Indonesia for Australia, were no longer in direct flight but rather were engaged in secondary movement seeking a more favourable refugee status outcome or a more benign migration outcome. We could credibly draw this distinction if we co-operated more closely with Indonesia providing basic protection and fair processing for asylum seekers there. Until we do that, there is no way of decently stopping the boats.

Little is to be gained by targeting Tony Abbott and Scott Morrison for describing unvisaed asylum seekers as 'illegals'. Labor leaders, past and present, have used the same term. For example, as The Australian recently highlighted, Julia Gillard has in the past spoken of the AFP disrupting people smuggling thus 'preventing more than 5000 foreign nationals coming to our shores illegally'. Kevin Rudd as Prime Minister spoke of getting 'the balance right in a hardline approach to illegal immigration, and treating the people who we are required to process in a humane fashion.' Kim Beazley, Leader of the Opposition at the height of Tampa crisis in 2001 said: 'We must not allow our immigration policy to be subverted by unchecked illegal arrivals. We must protect our borders.' Sadly, the dog-whistle effect of the label 'illegals' does nothing to enhance the prospect of reasoned dialogue about solutions to very difficult public policy questions.

The unnuanced language of our political leaders needs to be augmented by the fine judicial corrective of Justice Merkel in the Federal court case of Al Masri when he said: 'The Refugees Convention is a part of conventional international law that has been given legislative effect in Australia…. It has always been fundamental to the operation of the Refugees Convention that many applicants for refugee status will, of necessity, have left their countries of nationality unlawfully and therefore, of necessity, will have entered the country in which they seek asylum unlawfully. Jews seeking refuge from war-torn Europe, Tutsis seeking refuge from Rwanda, Kurds seeking refuge from Iraq, Hazaras seeking refuge from the Taliban in Afghanistan and many others, may also be called "unlawful non-citizens" in the countries in which they seek asylum. Such a description, however, conceals, rather than reveals, their lawful entitlement under conventional international law since the early 1950's (which has been enacted into Australian law) to claim refugee status as persons who are "unlawfully" in the country in which the asylum application is made.'

Three years ago, Patrick Keane, Australia's newest High Court Justice spoke at Monash University describing the Book of Deuteronomy as 'an example of a shared national morality that inspires its people to be generous, even to strangers. The idea is that we should treat everyone who comes within our borders, including complete strangers afflicted by misfortune, not just with respect and dignity, but with generosity, because we too have - at some time - been ourselves saved, without any particular merit on our part, from the misfortunes which are part of the human condition.' The descriptor 'illegals' does not help.

Let's now consider Jeff Crisp's third question: Can alternative (and better) approaches be found?

Boats carrying asylum seekers from Indonesia to Australia could legally be indicted by Australian authorities within our contiguous zone (24 nautical miles offshore from land, including Christmas Island). The passengers could be offloaded and taken to Christmas Island for a prompt assessment to ensure that none of them fit the profile of a person in direct flight from Indonesia fearing persecution by Indonesia. Pursuant to a regional arrangement or bilateral agreement between Australia and Indonesia, Indonesia could guarantee not to refoule any person back to the frontiers of a country where they would face persecution nor to remove any person to a country unwilling to provide that guarantee. Screened asylum seekers from Christmas Island could then be safely flown back to Indonesia for processing.

With adequate resourcing, a real queue could be created for processing and resettlement. Provided there had been an earlier, extensive advertising campaign, Indonesian authorities would then be justified in placing any returned boat people at the end of the queue. Assured safe return by air together with placement at the end of the queue would provide the deterrent to persons no longer in direct flight from persecution risking life and fortune boarding a boat for Australia. In co-operation with UNHCR and IOM, Australia could provide the financial wherewithal to enhance the security and processing arrangements in Indonesia. Both governments could negotiate with other countries in the region to arrange more equitable burden sharing in the offering of resettlement places for those proved to be refugees. Australian politicians would need to give the leadership to the community explaining why it would be necessary and decent for Australia then to receive more proven refugees from the region, including those who fled to our region fearing persecution in faraway places like Afghanistan.

Indonesia would need to enhance its own border protection regime making it more difficult for asylum seekers in Malaysia who are not in direct flight from persecution in Malaysia to enter Indonesia. The safeguards negotiated in Indonesia and any other country in the region to which unprocessed asylum seekers were to be sent would need to comply with the minimum safeguards set by the Houston Expert Panel when they reviewed the Gillard Government's proposed Malaysia Arrangement. These safeguards have not been met with the Gillard government's resurrected 'Pacific Solution'. Paris Aristotle told the ABC Lateline Program when discussing Manus Island in March 2013: 'But the panel was very clear. When we established the safeguards, we didn't say, "Here's a set of safeguards to mitigate against the risks. If you can do them great; if you can't, go and do it anyway." We were explicit. We said, "These safeguards need to be implemented as a part of any offshore processing arrangements."'

Designing a regional agreement in which Indonesia would need to play a pivotal role, all parties would need to have regard to the Houston Panel's observations about the inadequate Malaysia Arrangement:

There are concerns that relate to the non-legally binding nature of the Arrangement, the scope of oversight and monitoring mechanisms, the adequacy of pre-transfer assessments, channels for appeal and access to independent legal advice, practical options for resettlement as well as issues of compliance with international law obligations and human rights standards (particularly in relation to non-refoulement, conditions in Malaysia, standards of treatment and unaccompanied minors).

Persons who reach Australia whether by boat (having no genuine fear of persecution in or refoulement from Indonesia) or by plane, whether with or without a visa, should be detained onshore only for the duration of health, security and identity checks. They should then be released into the community being permitted to work and being eligible for social welfare assistance.

Once asylum seekers are released into the Australian community, they should be assured sufficient means or opportunity to live a dignified existence while awaiting processing. Just as Australia has long prided itself on providing a just wage and an adequate welfare safety net for all persons living in Australia, so too we should not drop our standards for those asylum seekers in the community awaiting processing. Just as people living in neighbouring countries do not have an entitlement from the Australian government to the same living standard as the poor and welfare dependent in Australia, Australia has no obligation to provide the same welfare assistance to asylum seekers waiting in or removed to transit countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

In the short term, Australia should escalate its diplomatic efforts with Indonesia to stem the flow of boats and to win agreement to the safe return by air of all asylum seekers interdicted within the contiguous zone or inside Australia's territorial waters once they have been screened out from having any protection claim against Indonesian persecution. Such efforts would need to include commitments to capacity building, countering corruption, and a review of the aid budget. Both governments need to have an incentive to stop the boats. Australia and Indonesia should then join a regional initiative aimed at:

- Setting down a regional principle of non-refoulement

- Setting down regional principles for denying entry and returning asylum seekers no longer in direct flight from persecution to the safe transit country they have just departed

- Setting down regional principles for processing and protection with certification by UNHCR

- Setting quotas for resettlement places for proven refugees who are processed in the region.

Then, and only then, might Australia have some prospect of achieving the policy goal of hermetically sealed borders and ordered migration flows, while honouring the letter and spirit of the Refugee Convention in a region where our neighbours are not much interested in signing the Convention but like us are committed to sharing the burden of extending compassion to those in direct flight from persecution. Then, and only then, might we stop the boats once it is known that it is a waste of money to take to the high seas only to be told: 'Please get back to where you already had a realistic opportunity for protection and processing; but if you are in direct flight from persecution, you are welcome here!' There would be no need to try unprincipled, unworkable deterrents like offshore processing in Nauru or Manus Island or offshore dumping in Malaysia. Unless we wrestle with these complexities, we risk a populist response to all asylum seekers, including those in direct flight from persecution: 'Get back to where you once belonged!' Jeff Crisp has done us a service highlighting how barbaric that would be, and how modest is the challenge confronting Australia compared with so many other countries which do not boast the advantages of which we dare to sing: 'Our home is girt by sea; Our land abounds in nature's gifts'; 'For those who've come across the seas we've boundless plains to share.'

The PNG Solution

I was in Myanmar oblivious to the planning and travels of Kevin Rudd and Tony Burke to Papua New Guinea during the week of 13-19 July 2013. On Saturday morning 20 July 2013, I landed back into Sydney to see full page advertisements simply stating, 'If you come by boat without a visa you won't be settled in Australia'. This wasn't John Howard; this is Kevin Rudd. During my week in Yangon I had the good fortune to catch up with Fr Bambang Sipayung SJ, the regional director of the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) for Asia Pacific as well as previous JRS directors for India and Sri Lanka. Talking to them, I was aware yet again that we Australians see ourselves as special. It's only the citizens of an island nation continent who can become so obsessed about the desirability of hermetically sealed borders. So what to make of it all?

Since the Houston Panel reported almost a year ago, it has been very clear that all major political parties in Australia are of the unshakeable view that there is a world of difference between an asylum seeker in direct flight from persecution seeking a transparent determination of their refugee claim which if successful will result in the grant of temporary protection, and an asylum seeker prepared to risk life and fortune to engage a people smuggler to obtain not just temporary protection but permanent resettlement in first world Australia. With the rapid increase in the number of boat people arriving from Indonesia this past two years and the corresponding increase in deaths at sea, I have been one refugee advocate prepared to concede this distinction, though claiming that the line is often difficult to draw. The line could be drawn more compellingly if there was a basic level of processing and protection in Indonesia, Malaysia and throughout the region which could be endorsed by the UNHCR. That is a work which would require a lot of painstaking high level diplomacy. And it definitely cannot be done before the 2013 Australian election. I respect those refugee advocates who think such a regional agreement would never be possible. But I still think it's worth a try. All decent Australians remain open to providing protection to fair dinkum asylum seekers in direct flight from persecution to our shores. The majority of voters think that the people smugglers and some of their clients are having a lend of us. The mantra of processing and permanently resettling all asylum seekers will not have any appeal to any major political party in Australia for a very long time to come.

Some refugee advocates in the past gave cautious approval to the Gillard Government's Malaysia Solution. That arrangement was based on the premise that it would stop the boats because no one would risk life and fortune to be amongst the first 800 to arrive in Australia only to be moved to Malaysia to join the other 100,000 people of concern to UNHCR. The Malaysia deal would not have resulted in any significant improvement to the upstream conditions for asylum seekers in Indonesia. It was simply a means of trying to stem the boat flow. Malaysia never made sense to me because no one could say what would be done with unaccompanied minors and other particularly vulnerable individuals. If kids without parents were included in the 800, the arrangement would be unprincipled; if not, it would be unworkable because the next lot of boats would have been full of kids.

In the short term, no government will stop the boats unless there is a clear message sent to people smugglers and people waiting in Indonesia to board boats. But that message must propose a solution which is both workable and basically fair, maintaining the letter and spirit of the Convention and Australian law.

When the High Court struck down the Malaysia Solution, the major political parties were united in wanting to cut the Court out of the action and in wanting to assure the public that the Parliament would maintain adequate scrutiny of the Executive. The law put in place required any proposal to be placed before both Houses of Parliament allowing our elected representatives to disallow the proposal. When our politicians approved Manus Island as a staging post for processing a few hundred asylum seekers most of whom would be resettled in Australia, they had no idea that they would be voting to approve a plan for permanent removal of asylum seekers from Australia. This may in part explain Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's statement on Friday, 'There will be those both in PNG and Australia who will seek to attack this arrangement through the courts, which is why we have been as careful as we can in constructing an arrangement which is mindful of the earlier deliberations of the courts'. In principle, the matter should be brought back to Parliament. Politically this would also make sense, locking in all major political parties.

UNHCR and Paris Aristotle, the refugee advocate who served on the Houston Panel, have been very critical of the facilities at Manus Island. The new minister Tony Burke rightly boasted as one of his first acts that he was removing all kids from Manus Island. Now under the mantle of the Australian parliament's approval of Manus Island, our government is planning to send there anyone and everyone who arrives by boat. It is imperative that kids without parents and other vulnerable individuals not be sent to PNG until UNHCR and advocates like Paris Aristotle can give the arrangements the tick.

When the Gillard Government resurrected Manus Island and Nauru, we all knew that this would not stop the boats. Andrew Metcalfe the previous head of the immigration department had told us so. This bold PNG move might stop the boats in the short term. Let's hope it does. But if it does, we need after the election to recommit ourselves as a nation to providing better regional upstream processing and protection for those asylum seekers stranded in Indonesia and Malaysia. If it doesn't work, we will be complicit in visiting further social problems on PNG and the Torres Strait where in the past we have permitted PNG residents to come and go fishing and socialising. The Torres Strait will now have to become the most policed boundary in Australian history. So much for the delights of an island home. Just as we have undermined Australian values by placing asylum seekers in the community without work rights and without adequate welfare, so too we will now risk undermining the values of Torres Strait Islanders who have long extended a welcome to their PNG neighbours.

In the long term, we, a first world country with a commitment to the Refugees Convention, will not stop the boats until we work co-operatively with our neighbours seeking better upstream processes and protection for asylum seekers in our region and negotiating an equitable distribution of resettlement places. Let's hope the boats do stop before the election. And let's hope that after the election whoever is in government can call a truce on the race to the bottom, committing to the hard diplomatic work needed for a regional solution to a regional problem. With every step like the PNG Solution, we Australians show the rest of the region that we are only special because we think we are; and we're not. Just judge us by our actions. When in a tight spot, we use our neighbours.

The 2013 pre-election Nauru gloss

With the calling of the election, the Rudd Government is now in caretaker mode. So there will be no more hastily drawn up memoranda of understanding with indigent Pacific nation states happy at a price to resettle genuine refugees who have set out for Australia from Indonesia by boat since 19 July 2013. Both sides of politics want to stop the boats, and they are now prepared to do almost anything (except embrace the other's policy positions) to try to arrest the people smuggler trade and the tragic deaths at sea. Whoever wins government on 7 September 2013 will need to bring the PNG and Nauru deals back to Parliament even if the High Court does not get to them first.

Like the PNG Agreement of 19 July, the agreement between the Governments of Australian and Nauru announced on Saturday and providing for resettlement of refugees (including unaccompanied minors) in Nauru has not been scrutinised or approved by the Australian Parliament. The Nauru agreement depends for legality on the fig leaf of parliamentary coverage given by the tabling of documents by Minister Chris Bowen on 10 September 2012 when he told Parliament: 'By presenting the designation and accompanying documents in accordance with the legislation, we are providing the parliament with the opportunity to be satisfied that they are appropriate. Again, I call on both houses of parliament to approve this designation, to enable the first transfers of offshore entry persons to Nauru and to provide the circuit-breaker to irregular maritime arrivals called for by the (Houston) expert panel's report.'

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) tabled by Bowen provided: 'The Commonwealth of Australia will make all efforts to ensure that all persons entering Nauru under this MOU will depart within as short a time as is reasonably necessary for the implementation of this MOU'. The Parliament did not disallow the designation of Nauru as a 'regional processing country' in September 2012 but that was because all parliamentarians including Mr Bowen thought that the proposal was that Nauru be a temporary processing country, not a permanent resettlement country.

On 3 August 2013, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd appearing with Baron Waqa, the President of Nauru, said, 'Today we are pleased to announce that we've reached a new Regional Resettlement Arrangement, one that supersedes the Memorandum of Understanding we signed last year.' Rudd was conceding that this new Arrangement bears no resemblance to the one presented to Parliament last September. The requirement to table such documents in parliament was legislated when the Parliament decided that it wanted to exclude the High Court from scrutinising future arrangements like the Malaysia Solution. The substitute was that the parliament itself would have the chance to disallow any arrangement entered into by the Minister for Immigration acting in what he considered to be the national interest.

Rudd went on to say, 'Our Governments have agreed that the Republic of Nauru will not only maintain and extend its regional processing capacity, but it will also provide a settlement opportunity to persons it determines are in need of international protection.' On the eve of calling the election, he has attempted to do this spared all scrutiny by the High Court and the Parliament. The Rudd Cabinet has purported to be completely immune from all supervision by the other arms of government when deciding to ship asylum seekers, including genuine refugees, across the Pacific Ocean to very precarious futures.

On 3 August 2013, Tony Burke, the Minister for Immigration, conceded that Nauru was no place to be sending fit young adult male asylum seekers because the locals are very upset by the recent destruction of the processing centre by other fit young adult male asylum seekers. So we will send kids instead!

Since 19 July, the Rudd Government has been committed to a campaign of shock and awe trying to stop the boats. Like nuclear deterrence, such a campaign might be ethically justified provided the homework has been done to ensure that the threat has maximum effect reducing as far as possible the risk of having to do immoral damage to people. The necessary advertising and messaging is yet to be rolled out in Indonesia. It should have commenced before or when the threat was issued.This government blunder has resulted not in stopping the boats but in two thousand people still boarding boats and now being condemned to immoral damage. Neither have the detailed arrangements been put in place to ensure appropriate accommodation, processing and resettlement in PNG and Nauru. Julia Gillard's Malaysia deal took months to negotiate. The government's message this time should have been, 'Any one who now boards a boat will not be resettled in Australia. They will be resettled in another country under arrangements complying with the requirements stipulated by the Houston Panel when it reviewed the Malaysia Arrangement. We are committed to working with everyone, including the Opposition, to set in place the immediate measures to stop the boats. The last thing we want is for people to get on boats now not only risking their lives, but being guaranteed devastating outcomes in other countries in the region.'

In the medium term, the boats can be stopped only through a negotiated regional agreement with Indonesia and Malaysia at the table. Like many Australians, I had hoped that the dastardly plan announced on 19 July would stop the boats in the short term, as a stop-gap measure. It is dismaying to learn that appropriate consultations had not occurred with Indonesia with the result that the very people who were to receive the shock and awe message are yet to receive it. It is also dismaying to learn that the detailed negotiations demanded by the Houston Expert panel were not concluded with PNG and Nauru before bold press announcements made chiefly for local electoral consumption. There's only one thing worse than shock and awe; that's shock and awe that doesn't work because you haven't done your homework. Prime Minister Rudd or Prime Minister Abbott will spend a lot of time in the next year cleaning up the mess and attending to the legitimate claims of the 2000 and more people to whom we forgot to send the shock and awe message of doubtful legality before implementing its dreadful consequences.

The way forward after September 7

The major political parties in Australia are now strongly committed to stopping the boats. During the election campaign, Messrs Rudd and Abbott are keen to demonstrate that each is more decisive, determined, and punitive than the other. They are ad idem on the end to be achieved; the only thing they won't do is embrace the other's means for achieving the end of stopping the boats. In the first of the election debates, Tony Abbott said, 'We will salvage what we can from the arrangements that Mr Rudd has made with PNG', and Kevin Rudd contesting Abbott's assertion that he would turn back the boats because it is rarely safe to do so said, 'If we didn't think that problem existed we'd have a different approach'. I have six recommendations for the way forward. (1) Whoever is elected Prime Minister on 7 September 2013 should introduce a bill to Parliament detailing the measures aimed at stopping the boats, thereby putting beyond legal doubt the shock and awe measures implemented on the eve of the election campaign and locking in the major political parties so that petty party point scoring might cease. The debate on the bill will allow both sides of the Chamber to purge themselves of the hypocrisy that has accompanied Labor's unctuous condemnation of John Howard's Pacific Solution and the Coalition's unctuous condemnation of Julia Gillard's Malaysia Solution. The bill would undoubtedly win the support of all major political parties. It should list a cocktail of deterrent measures including all those agitated by both major political parties. The new government should then commit to: (2) an increase in the humanitarian quota; (3) a negotiated agreement with Indonesia and Malaysia aimed at upstream improvement of processing and protection; (4) an ethical reassessment of the plight of those who came after 19 July 2013 without notice of the new shock and awe policy; (5) a pledge to care for unaccompanied minors who arrive in Australia's territorial waters until they can be safely resettled or safely returned to their family or to the guardians in transit from whom they were separated; and (6) safeguards, including a transparent complaints mechanism, in PNG and Nauru consistent with the safeguards recommended by the Houston Panel for both Pacific processing countries and for Malaysia under the Malaysia Solution.

When the going gets tough and the way ahead is not clear, we Church people can take to heart the observation of Morris West:

The pronouncements of religious leaders will carry more weight, will be seen as more relevant if they are delivered in the visible context of a truly pastoral function, which is the mediation of the mystery of creation; the paradox of the silent Godhead and suffering humanity.

That's what Pope Francis did at Lampedusa. At all times in the public domain, whether in dialogue with government about social policy or in giving a public account of church perspectives, we who speak with a Church mantle must speak with the voice of public reason. Therein lies the tension. Without trust between those whose consciences differ, we will not scale the heights of the silence of the Godhead nor plumb the depths of the suffering of humanity; we will have failed to incarnate the mystery of God here among us. This mystery is to be embraced in the inner sanctuary of conscience where God's voice echoes within, to be enfleshed in the relationships we share as the people of God, and to be proclaimed in our calls for justice in the public domain. The need is urgent given that our two major political leaders and their two acolytes in the migration portfolio – Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott, Tony Burke, and Scott Morrison – are publicly professed Christians committed to stopping the boats at almost any cost. Yes, they want to stop deaths as sea, but they want to stop much else as well, and not primarily for the well-being of those on the boats. With his Anglo-Catholic liturgical interests and his capacity to engage in dialogue with everyone from Bourke to Oxford, Barry Marshall would expect us to be able to contribute deftly to this moral challenge of secure borders, a coherent migration policy, and due regard for our international obligations to those on the high seas coming our way seeking asylum.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at Australian Catholic University, and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University. 'The public, the Church and asylum seekers' is from the 43rd Barry Marshall Memorial Lecture, delivered at Trinity College Theological School, Old Wardens Lodge, Royal Parade, Parkville, 14 August 2013.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at Australian Catholic University, and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University. 'The public, the Church and asylum seekers' is from the 43rd Barry Marshall Memorial Lecture, delivered at Trinity College Theological School, Old Wardens Lodge, Royal Parade, Parkville, 14 August 2013.