Our public debates are often marked by hostility and exclusion. Many of them touch on identity, and seem to say more about the protagonists than about the issues. Underlying and adding to the heat of such debates are questions about Australian identity. Can a Muslim, a Jew, an opponent or supporter of Israeli actions in Gaza, be regarded as authentically Australian, for example? Though the debates are usually vituperative in tone and simplistic in argument, they raise, however, deeper questions about why they start and what fuels their energy.

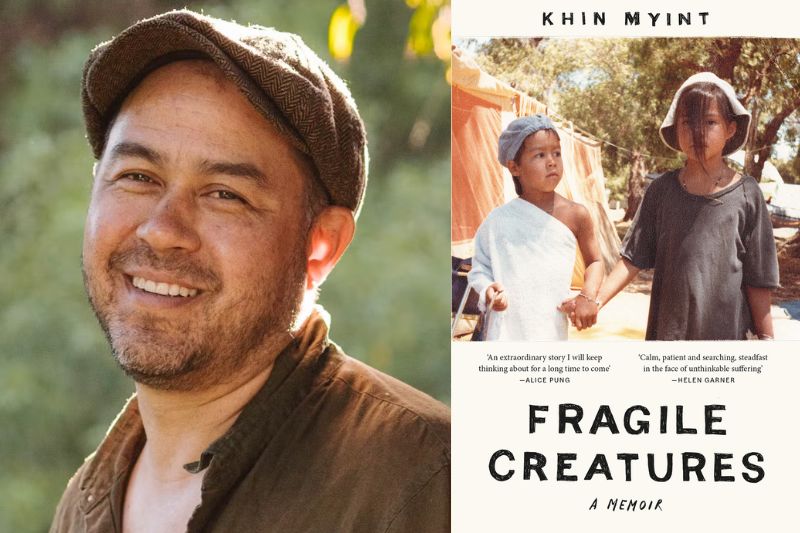

My reflection on these questions was sparked and clarified by a recent book Fragile Creature: A Memoir, by Khin Myint. He was born to a Myanma father and an Australian mother, each of whom wanted their children to identify with their own culture. At school in Perth at a time of xenophobic violence he was rejected and violently bullied by white Australian students. Nor did he belong to tight group of Asian students. His attempts to win acceptance ended in further humiliation. His experience at university was similarly marked by lack of understanding, and led to two attempts at suicide. He found relief in moving from Perth and studying psychology. After similar experiences at school his sister fell ill and his parents separated. His sister was treated by many doctors, all totally confident of their diagnosis and of their expensive, painful and unavailing treatments. Khin returned to Perth to study, visited her when hospitalised, until her eventual suicide.

At university he met and became engaged to a student from the United States. Khin believed his new fiancée was dominated by her mother, who saw him as an unsuitable husband, and cancelled the engagement. When he went to the United States to reason with her, she secured an exclusion order against him that he eventually had overturned. He then returned to Australia.

This outline indicates the constant struggles about identity that surrounded Khin’s life. His childhood pressure to identify as Australian or Mynama, his violent rejection by Australian children and perceived exclusion by Asian students as a half-caste, leading to further experiences of rejection and self-harm, to study that provided a language and framework for self-understanding, while having to respond to the ambivalence and later rejection by his fiancée, and the need to support his mother and sister.

Such a history might lead us to suspect that his memoir will be raw and harrowing. It is anything but. The wonder of the book lies in his calm and magnanimous reflection on his experience and in his attempt to understand his parents, sister, fiancée, those who treated him poorly, those who promised certainty with their diagnoses and treatment but delivered only pain, and those who stood by and watched. His memoir is illuminating and generous, a simply and beautifully written book by a good and wise man. It also provides a lens for reflecting on the dynamic at work in public debates that touch identity.

Khin’s story illuminates the dynamic of bullying directed against persons who are different. It affects both those bullied and those who bully. Those who bullied him and his sister shared an understanding of Australian male identity as white, aggressive, tough, fearless and intolerant of difference. That identity, however, provoked anxiety within those who assumed it because it led them to deny their own fears and craving for acceptance. It was unachievable. Their anxiety betrayed the fragility of the mask they wore and so needed to be suppressed. It was triggered by people like Khin who did not or could not fit the imagined Australian identity. Their marginality threatened the rigid definition of Australian masculinity. They were a threat to be met by humiliating and destroying them.

Those who sought acceptance and equality, but found only brutal rejection and subjugation because of their perceived difference, often denied or were ashamed of central aspects of their own identity. Their humiliation could lead them to blame themselves for their ill treatment. If they did so, they buried their anger, pain and grief, and persisted in trying to assume an identity approved by society. Their denial could then manifest itself in mental and physical illness.

Khin’s experience led him to reflect deeply on the tension between an identity assumed in response to humiliation and the denial of the hurt underlying it. He saw it in himself, his family and close friends. His father responded to exclusion in his work in Australian society by assuming an uncompromising Myanma culture and by pressuring his children to adopt it. His sister responded to bullying and exclusion by trying to fit in and by denying the feelings associated with exclusion. The doctors who treated her appear to have assumed the identity of the infallible healer, and as a result to have imposed certainly harmful treatment on the strength of doubtful diagnoses. Only in psychotic episodes could she express the feelings of her real self. Khin’s fiancée was dominated by a strong mother who imposed on her an identity defined by career, marriage and ambition. In Australia she tried to break out of this narrow identity associated with these demands, but when torn between Khin and her mother and by her anxiety about identity she turned abusively on Khin and tried to destroy him.

In all these relationships, people froze the complexity and fluid aspects of identity into brittle certainties. This polarising of human identity and choice was an expression of anxiety, which led them to humiliate and shut out those who threatened their assumed identity.

This dynamic may illuminate the heat and viciousness of Australian conversation about Israel and Gaza. The anger is readily understandable in protagonists whose origins and relatives lie in Palestine or Israel. But it is less clear why Australian public figures and commentators should reduce the debate to one between support of Hamas and Israel, should pillory politicians, journalists and university heads who wish to make a space for debate about the complex issues involved, should ostracise politicians who speak on behalf of the people of Gaza, and should place so little moral weight on the disproportionate suffering and death inflicted on the people of Gaza.

Khin’s analysis suggests that the heat and hostility with which this cause is prosecuted against those who do not support Israel in the war may reflect anxiety about what it means to be Australian. For them to be genuinely Australian is to take sides in combative and polarised sets of relationships. Those who fail to show due deference by assuming the equal value of Christian and Muslim lives and of the Western and Eastern cultural inheritance, and who insist on the complexity of relationships, threaten this brittle identity and so must be humiliated and driven from the public sphere.

Khin’s memoir perhaps also suggests how to respond to people caught up in this kind of violence. The highest priority should be to look out for and offer support to those who are targeted. They are vulnerable, and too often bystanders are afraid to reassure them or, worse, assume that they must be at fault. The more difficult and counterintuitive step is to try to understand and have compassion for those who target others. They need encouragement to discover a more human identity. The least helpful response is to meet violence with violence and insult with insult. That confirms the anxiety of their opponents, their resultant simplification and polarisation of the issue at stake, and the brittle sense of identity that underlies their violence.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.