Homily at requiem for Peter Steele SJ, Chapel of Newman College, University of Melbourne, 2 July 2012

Preaching here in this Chapel some weeks ago Peter Steele alluded to the text I have just read, the beginning of the Gospel according to St John, and remarked:

It is profoundly mysterious of course, and the mystery begins with the that expression, 'the Word'. We might say that Christ is part of the eloquence of God.

The ‘eloquence of God’: what a wonderful phrase, coined by Peter, to bring fresh life to an ancient article of faith. And how appropriate to recall it now when we are gathered here to celebrate his requiem—Peter, who was so constantly here in this Chapel eloquent about God.

And eloquent, not only about God, but about so many other aspects of life, chiefly literary and artistic, in the wider context of this College and this University.

It will fall to others more qualified than I to pay tribute to Peter’s achievements as scholar, teacher and poet. Many such tributes have already begun to come in. In this Requiem homily I shall speak of Peter as friend, Jesuit and priest, eloquent about God.

The first sight of Peter, over fifty five years ago, was not, as I recollect, all that promising of friendship to come. He had arrived at the novitiate early on the day appointed for entry after the long train journey from Perth. The rest of us had put off our arrival until the last moment, leaving Peter to a wearisome wait for companionship the whole day long. He had then, and—I think even his close friends would agree—retained throughout his life, a capacity to give a fixed look, the kind of look that a sergeant major would have found very useful on parade. It took some time for us, equally though less eloquently confused about it all, to grasp what a remarkable and lovable companion had come to us from Perth.

‘In the beginning was the Word. And the Word became flesh and pitched his tent among us, and we saw his glory, full of grace and truth’ (John 1:1, 14).

In the second-last conversation I had with Peter, we agreed that that text should be the Gospel for his Requiem. In the halting words of our last conversation, he reiterated that it was very much the right choice. There is a sense, I’m sure, in which every poem that Peter wrote was an instance of the Word becoming flesh. Our Irish novice master, Ned Riordan, whom Peter loved and admired as much for his wit and intelligence as for his holiness, once made a throw-away remark that greatly intrigued him: ‘Where most people look out a window and see a cow, a saint sees a creature’. Peter looked out at the world and acquired from his voracious reading an incredible knowledge of anecdotes and facts—quaint, technical, arcane—most of them remote from anything overtly religious or theological, and found in them a spark of the divine glory.

In his early days I sensed in him a certain reserve regarding the Jesuit poet Gerald Manley Hopkins—a reserve towards a figure against whom he might be too readily measured. But some lines from Pied Beauty give perfect expression to what drew Peter into the particularity of God’s creation:

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him.

Peter was very much the Scholar described by the sage Ben Sirach in the 1st Reading:

(who) seeks out the wisdom of the ancients,

preserves the sayings of the famous

penetrates the subtleties of riddles,

seeks out the hidden meanings of proverbs

and is at home with the obscurities of parables.

(Who) sets his heart to rise early

to seek the Lord who made him,

who opens his mouth in prayer

and asks pardon for his sins.

Peter, who was never a good sleeper, certainly set his heart to rise early. And it was as an early riser that he would meet those other early risers and workers: the janitors, porters, and cleaners of the buildings where he worked. And he greeted them not as a busy academic rushing past on his way to higher things, but as a fellow human being, going to his labour as they were busy about theirs. The unfailing courtesy, the witty and cheering word that won their respect and affection flowed from his profound humility, his sense of being thrown into the mix of humanity and standing in as much need of God’s grace and succour as anyone—he, who had so little to be modest about.

If he was much loved, as well as respected as Provincial, it was because he met everyone on this simple human level. No one in the Province, no matter how far below him in education, ever felt the weight of his words or put down by his learning. What a blessing for us to have a Provincial who could sit alongside us in our humanity and use his great intelligence, wisdom and articulacy, simply to help us name and so render more manageable our hopes, our fears, our sorrows and our aspirations.

A man fearlessly immersed in the university world and the contest of ideas, Peter never ceased to point and provoke us to be similarly outward-looking to the world. He often appealed to another Johannine text: “God so loved the world …” (3:16) and stressed that the world that God so loved—and gave his Son for its life—was not some sanitised or past world but the present world in all its squalor, violence and meanness, as well as its beauty, decency and love.

Peter was ordained a priest in Perth on 12 December, 1970, the same day as five others of us were ordained here in Melbourne. In preparation for that event we had been sent off to the Carmelite Sisters at Kew to be measured for albs according to our various bodily proportions. No less than 41 years later when concelebrating with Peter a Mass for the Golden Jubilee of his devoted friend Sr Margaret Manion and my own Loreto Sister, I was startled to see Peter putting on exactly the same alb. Alas, it was not the garment that once it was, nor by now was Peter the slim ordinand that once he was; the strain upon zips and stitches all too clearly showing a growth in stature as well as wisdom before the Lord. But the fact that Peter still wore that alb—besides being a tribute to the needlework of those good sisters many years before—said something the kind of priest he felt he had been ordained to be.

The ‘cultic’, the ‘celebratory’ aspect of the Mass—not so much stressed in post-Vatican II years—was central for him: the proclaimed transformation of bread and wine, the handling of the sacred vessels, the gestures and movement of the Mass as ‘dance’. Last year in his memorable Radio National Encounter interview with Margaret Coffey Peter said that what priesthood has in common with poetry is that each of them has to do with celebration. He went on:

the cultic side of priesthood, which still is mainly the Eucharist, is what sort of besots me the older I get. The word ‘Eucharist’ means saying ‘Thank you’. I think that God can never be thanked enough for being God and for sending his Son Jesus to be both God and a human being. There is no end to the amount of celebration which this warrants.

If the Incarnation—the Word become flesh—was the central truth of the Christian faith for Peter, he also celebrated in countless poems and sermons the joy and splendour of the Resurrection. He was ever conscious, however, that the path from Incarnation to Resurrection led through the divine vulnerability that climaxed at the cross. If Peter was a kind and compassionate priest, a faithful and sympathetic friend, it was so because he had personally plumbed and felt the brunt of human alienation and despair. He was no stranger to depression, could swiftly oscillate in mood between high and low.

For Peter the supreme moment of divine eloquence occurred at Calvary—an hour when the divine Son uttered very little but was stretched out, nailed and lifted from the earth in a helplessness of love eloquent beyond discourse of any kind. His 1986 poem Crux speaks so typically of Peter before that divine humility that I cannot forbear reading it now.

Crux

Seeing you go

Where the dead are bound, and having no resource

To twist those timbers out of their lethal course,

I want at least to know

What I can say

Now that the boasts have blown away and even

The cursing has grown faint, while the pall of heaven

Abolishes the day.

I was never wise

In word or silence, never understood

The killer in my members, thought of good

At what one might devise

From scraps of evil.

How can I learn a way for me or mine

To stand beside you? Vinegar, not wine,

Is all we give you still.

Among the dice

And the dirt, with more of shame than love to show,

All that will come to heart is ‘Do not go

Alone to Paradise.’

As he lay dying in Caritas last week, I asked him whether he remembered that poem. ‘Indeed I do’, he said. He was living—or rather, dying—it now.

As long as I’ve known him Peter has always lived in close consciousness of mortality. In the college library where we did our early studies in Philosophy there weren’t many books that were not in Latin. But Peter found his way to a treatise of Karl Rahner on Death and it left a mark upon his imagination and his writing that never went away. Nor was this preoccupation with mortality merely theoretical. I know there are many of you here present who have experienced Peter’s priestly accompaniment through tragedy and loss in a deeply human way. Whether that was in the context of explicit Christian faith or no faith at all, Peter knew what to do and say.

Of his own mortality, he said, again on that Encounter program:

I believe it is a condition … let’s call it a room, which is what John Donne called it, which precedes and leads into a capacious and entirely blessed and secure immortality, one of whose names is heaven. And I believe in that very, very strongly. And I probably believe that more strongly than almost anything else.

To speak personally, it has always been a great sustenance for my own faith that Peter, who read everything, heard everything that could be thrown against the faith—in the name of so much suffering, so much evil—and who was constantly in conversation with friends and colleagues who did not share his faith, could hold to the end that ‘assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen’ (Heb 11:1). Peter’s faith was simple in the best sense, his piety unostentatious but profound. When you visited him in his room in the Dome, there was his Breviary open, his vow crucifix close at hand.

Many have remarked on the equanimity with which Peter accepted his terminal illness and the medical procedures it increasingly required. The poem Rehearsal is, I believe, his Nunc Dimittis. He addressed it publicly on several occasions in recent months, including what was to be in fact his last class of all, given to our Jesuit students at Jesuit Theological College early in May. Several times, in the course, of that event, granted his physical condition, I tried to bring the session to close but, try my best, he kept on explaining, drawing out responses—the teacher to the end.

The poem is too long to read here in full. Basically, it’s a reverie while preparing (Peter the cook in action to the last!) the ingredients of a meal. He runs through all those places in a life of travel to which he must now say ‘Farewell’. Here is the final stanza:

But here’s the mint still on my hands. A wreath,

so Pliny thought, was ‘good for students,

to exhilarate their minds.’ Late in the course,

I’ll settle for a sprig or two -

the savour gracious, the leaves brimmingly green -

as if never to say die.

Farewell, but once again the hint of resurrection.

The ‘wreath’ motif must have appealed to Peter. It features also in a line from a poem he wrote to commemorate our mutual Golden anniversary in the Society:

‘Yesterday’s vow goes on wreathing its way through the heart’.

Peter’s vowed life as scholar, teacher, poet, priest, wit and friend has wreathed its way through our hearts—hearts that so keenly feel his loss. His immense legacy, in memory and print, will ensure that his eloquence about God remains.

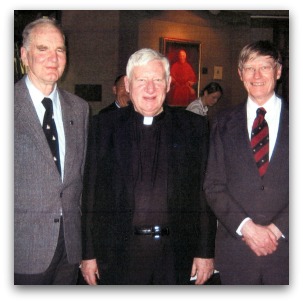

Pictured above: Jesuit contemporaries Andrew Hamilton, Peter Steele and Brendan Byrne, at Newman College.

Brendan Byrne teaches New Testament studies at the United Faculty of Theology, Parkville, in Melbourne.

Brendan Byrne teaches New Testament studies at the United Faculty of Theology, Parkville, in Melbourne.