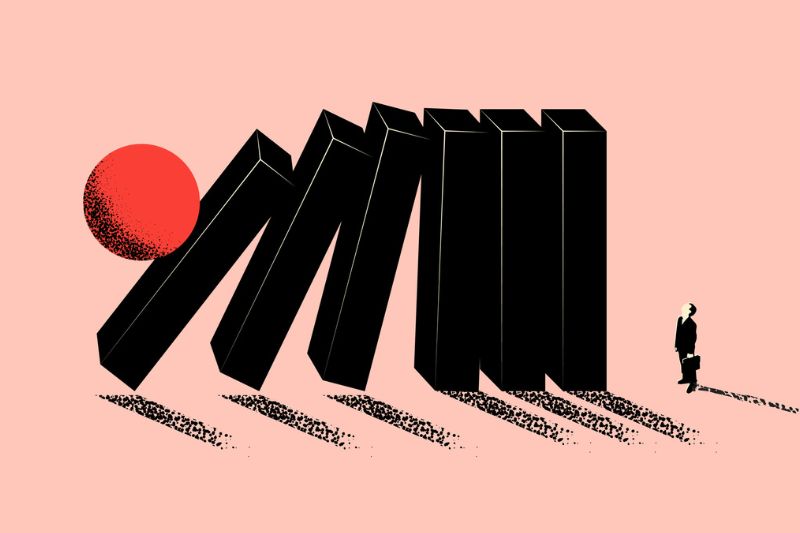

When you look through a peephole at a wide landscape, it is inevitable that you will only get a small part of the picture. That is what happens with much economic commentary in Australia. There is a tendency to assume that the system is simple enough to be understood by correlating a few of the more obvious statistics. It is not, and that is why the most pressing social issues, especially a deeply damaging generational divide between those who have property and those who don’t, are not addressed.

The way economic analysis tends to be conducted is reminiscent of the famous, or infamous, Phillips machine – sometimes called the Monetary National Income Analogue Computer (MONIAC) device.

In 1949, a New Zealand engineer and economist Bill Phillips unveiled a mechanical economic model that was supposed to demonstrate, by pushing coloured water through clear pipes, how money moves through the economy and what would happen if tax rates were changed, or there were increases in the money supply, or there were changes to other parameters, such as wages.

The machine was far from a success – human behaviour turned out to be frustratingly complicated and unpredictable – and the original version now sits as a quaint relic in the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s head offices.

Yet such mechanical thinking persists. Thus, when Australia’s wage growth nominally outstripped inflation for the first time in three years, recording a 4.2 per cent increase in the December quarter, a certain amount of alarm was evident in the business community and more right leaning economists.

Why? Because in their view higher wages means more money sloshing around the ‘pipes’, which will result in stronger demand and cause higher inflation. It would also reduce employers’ profits, which a cynic might say is the real reason for their complaints (a cynic would be right).

Thus Innes Willox, chief executive of the national employer association Ai Group claimed the increase is a clear sign that inflationary pressures are still here. ‘As the Reserve Bank has warned, sustainable real wage increases depend on an increase in productivity,’ he cautioned. ’Yet, according to the most recent national accounts data, over the year to the end of September 2023, Australia’s productivity as measured by GDP per hour worked fell by 2.1 per cent.’

'Working age people are more likely to be saddled with higher mortgage payments or higher rents. Many households with mortgages are experiencing intensifying financial stress.'

It all sounds persuasive enough until you examine the assumptions and the meaning of the words. First, if higher wages does mean more demand for those things recorded in the consumer price index (CPI) will that necessarily push up those prices? Only if they are sensitive to higher demand (assuming people actually want to spend more on those CPI products, which may not happen). A lot of the recent inflation came from changes on the supply side, especially when Covid affected global supply chains. It is stating the obvious to say that supply costs may continue to be volatile, depending on how the various wars in Ukraine and the Middle East unfold.

Second, does looking at ‘productivity’ help us? Not much. Productivity, which measures how much money you get when you sell your product compared with how much money you put in, is essentially a circular measure.

It is not the same as efficiency. ‘Efficiency’ is a measure of how many widgets come in, relative to the money you put in. Improving efficiency across an industry sector can actually result in lower productivity if competition leads to tighter profit margins and weaker prices. Witness, for example, how prices for many manufactured goods have fallen over time as production became more efficient. According to conventional analysis that means productivity fell.

Rising productivity simply means you can charge more – proving that you can charge more. It is all suspiciously circular, yet the term is used to bash workers, the implication being that somehow they have not been trying hard enough and so do not deserve to get higher wages.

In the real world, away from circular arguments and simplistic assumptions, the wage rises to Australian workers, after taking into account inflation, have been tiny. Higher energy and petrol costs have affected households’ real (after inflation) income and restricted much of the discretionary consumption. The savings rate, which was over 20 per cent during Covid is headed towards zero.

The aggregate picture of the economy may seem healthy enough after two years of heavy immigration, over 800,000, and the return of students and tourists. But the elephant in the room remains. Australia is a two-tiered society sharply divided between people who own homes and people who do not.

This deeply unhealthy generational split has been mostly ignored by politicians and the financial authorities for 25 years. Instead, they just peered through the peephole at their limited range of measures and concluded that things were fine. They purred over weak consumer price inflation numbers (until recently) and largely ignored the out-of-control asset inflation in the housing market.

The generational divide is worsening. Older people, who are more likely to own their homes, have been less affected than working age people by cost of living increases. Working age people are more likely to be saddled with higher mortgage payments or higher rents. Many households with mortgages are experiencing intensifying financial stress.

To address the issue it is, at a minimum, necessary to reign in the reckless bank lending that has left Australia’s household debt levels as some of the worst in the world. It is also essential to realise that looking at measures like CPI inflation, GDP (gross domestic product), wage rises and productivity is nowhere near enough to understand the complete picture.

David James is the managing editor of personalsuperinvestor.com.au. He has a PhD in English literature and is author of the musical comedy The Bard Bites Back, which is about Shakespeare's ghost.

Main image: (Getty images)