I knew this particular book was hiding somewhere, but was still surprised when I found it while looking for something else entirely. It was at the bottom of one of numerous boxes I have to use in order to cope with the number of books in this house. (I swear they reproduce under cover of darkness.) There it was, with its appropriate royal blue cover and stamped gold crown not coping too well with the ravages of time and the harsh Greek climate.

The Queen Elizabeth Coronation Book was published and released a few months ahead of that other coronation in June, 1953. Some things never change, although I’m not sure about coronation publications this time round. But the BBC recently ran a segment on the ceramics industry, which showed a veritable army of potters and painters readying souvenir plates and mugs for May 6. And all workers were saying what a privilege such work is.

My maternal grandmother’s crabbed handwriting on the book’s fly-leaf is still very clear. With lots of love and every good wish. She had known I wanted this book for my birthday, an occasion that rolled around a good two months after the Coronation, but a period when the excitement of the great day and the memory of its lengthy preparations were still lingering.

It seemed that the whole primary school had been preparing for months for the display we were to present at the local football ground. We paraded up and down repeatedly in rehearsal rows of three, while letters went home to instruct mothers as to their responsibilities: each child had to wear a cape in red, white or blue. I remember feeling very inferior and deprived when I scored a white one, which in reality was an old sheet that was definitely less-than-Persil-white: luckier children were clad in red or blue crepe paper.

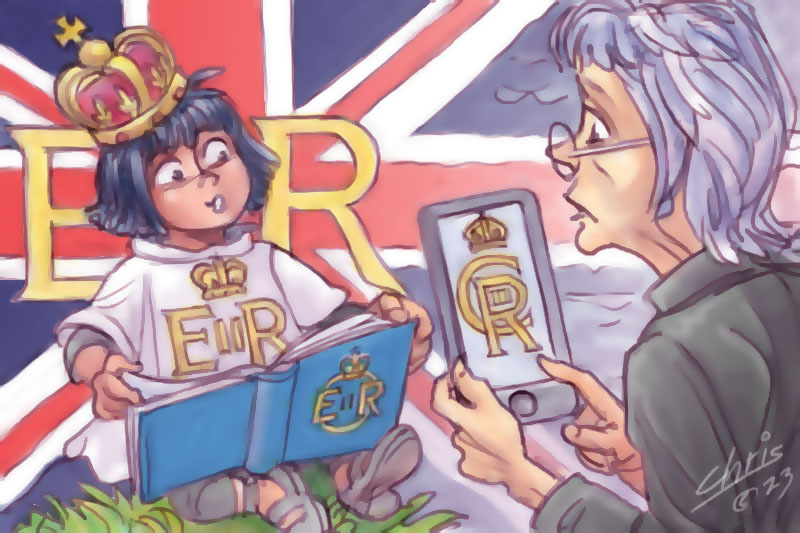

I was also very jealous of my younger sister, who was decked out in full Scottish regalia on the day, and took her place on one of the floats, depicting scenes from British history and representations of Empire, that moved slowly around the boundary line, while lesser mortals (me in my white sheet) obeyed orders. We marched into position in the centre of the ground, and then awaited the signal to kneel and crouch, thus forming the display ER II. One of my classmates, with whom I’m still in touch after all these decades, can still remember that he was on the bar of the E, but I can’t remember where I was , or what colour cape he had: I just bet it wasn’t a bit of old sheet, though. The whole effort must have looked quite good from the air (the township had an aero club), or from the highest row in the not-very-grand stand, but of course we kids saw only a few capes to the front and to the sides.

How times have changed. Way back then we swore the oath of loyalty every Monday morning. I love God and my country/I honour the flag/ I serve the Queen and cheerfully obey my parents, teachers and the laws. The flag was always flying, and school heads always had a portrait photograph of the Queen on their office walls. In my lavishly illustrated book, the great names of contemporary photography are there: Beaton, Baron, Marcus Adams, Karsh of Ottawa.

'There are also rumblings of discontent about the cost of the Coronation. The British Government is to pay for the occasion, but of course this really means that the taxpayer is to foot the bill at a time when so-called ordinary people are trying to cope with energy bills, the rising cost of living, and the rate of inflation.'

The Foreword of the book tells us that the Coronation of an English Sovereign is at once an awe-inspiring reality and a symbol. The reality, we were told then, was the might and wealth of a great Union of Free Nations (the word Empire does not appear) paying tribute to the power that binds them together. The symbol is the dedication of this power, embodied in the single person of the Sovereign, to the service of God.

I’m not sure that anybody today will consider King Charles’s coronation an awe-inspiring reality, although it goes without saying that the ceremony and accompanying pageantry will be spectacular. And many people want to do without the symbolism altogether. With the revelation, for example, that the monarchy has long been involved in the slave trade, disillusionment is ever-expanding: people can no longer concentrate on the abolition efforts of the early 19th century, when they learn about the first Elizabeth and slave trader John Hawkins. There are also rumblings of discontent about the cost of the coronation. The British Government is to pay for the occasion, but of course this really means that the taxpayer is to foot the bill at a time when so-called ordinary people are trying to cope with energy bills, the rising cost of living, and the rate of inflation.

I don’t doubt I will be glued to the BBC at the relevant time, but right now I’m going to put this ancient book back in its box.

Gillian Bouras is an expatriate Australian writer who has written several books, stories and articles, many of them dealing with her experiences as an Australian woman in Greece.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.