On the day Peter Haffenden died the waters of the Maribyrnong River were rising, the floods peaking, lapping at the doors of Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West. Peter passed at 4.24am, with his partner Kerrie Poliness, and daughter Phoebe, by his side. That afternoon, as Peter lay in state in the bedroom of his Footscray home, young volunteers shifted documents from the museum for safekeeping in the weatherboard house. Among them, the negatives of thousands of photos taken by Peter during his long association with the museum.

The Venerable Thich Phuoc Tan, the abbot of the Vietnamese Quang Minh Buddhist Temple in Braybrook, arrived soon after to pay his last respects to his long-time friend. The abbot sat beside the bed where, defying the odds, Peter held court for a stream of visitors during his final eight weeks. The abbot wished him a safe journey and encouraged him to stay grounded whilst being open to the vastness of the skies. He then invited those of us who were there to pick a flower from the riotous garden, to place on the bed beside Peter while we delivered him a final message. I chose a blazing red geranium, and my message was simply: ‘Thank you Peter for the many gifts you have given me.’

Since he passed much has been said about Peter Haffenden’s many accomplishments and I will touch on some of them. But this is a personal tribute, and I wish above all to speak of gifts — and of Peter’s magical, mischievous and expansive way of moving in, and seeing the world.

Peter spent his summers in Point Lonsdale, camping on the family block. He was an acute observer of the skies and an expert reader of the ephemerous. On summer nights when Venus was rising and casting its reflection on the sea, Peter would make his way to the bay, bucket in hand, wade into the shallows, and collect water where the reflections fell. He would later seal it in bottles he found in antique shops and hand them out as gifts to friends. Now that is magical.

As too was Peter’s love of stones. For decades, he collected quartz stones by the sea. White, and as smooth as bone. As Peter liked to say, give or take a few millennia, they were well on the way to becoming a grain of sand. Over the years he gave them to friends who were going overseas. There are stones now imbedded in a Shinto Temple in Japan, on the banks of the Danube, on New York’s Ellis Island, on Ireland’s sacred mountain, Croagh Patrick, in the grounds of the Kremlin and the Colosseum, and in Tiananmen Square and the Great Wall of China, among many places. Together, they form a hidden necklace around the earth. Peter, and his co-conspirators, Kerrie and Phoebe, each wore a piece of quartz which he had mounted in silver and made into a necklace. Again, magical. And inspirational too. It gets you reflecting on how you live your own life, and what kinds of crazy, daring projects you can conceive — and act on.

Perhaps the most cherished gift I received from Peter were the exhilarating conversations we had since we first met back in the late 1960s, during our university undergraduate days. Many concerned water — the seas and rivers, and oceans and lakes, and our mutual love of Port Phillip Bay and the Maribyrnong, aka Melbourne’s ‘forgotten river.’

'Three weeks after his passing, hundreds of friends from many walks of life and backgrounds gathered at the Living Museum to celebrate Peter’s life. Uncle Larry Walsh performed a smoking ceremony. Friends, collaborators and family members spoke, long-time friend and cabaret artist Tim McKew performed Life is Just a Bowl of Cherries, and many attendees stayed on late into the night to recall Peter’s magic.'

Peter did a lot to make that river known. He talked, but he also walked the walk. Big time. He transformed his lateral ideas and visions into practical projects and brought them to fruition, many under auspices of the Living Museum of the West. Peter’s 38-year association with the museum began at its inception. It was first located in a worker’s cottage in Footscray, and then in its permanent home in Pipemakers Park, above the banks of the Maribyrnong. Peter was employed as its inaugural media co-ordinator in 1984 by the museum’s first director, Olwen Ford. He brought to the job his skills as a photographer, researcher, and his stints as an ABC and Age journalist. And, above all, his intimate lifelong connection to the West.

Born and raised in Footscray and Maidstone, Peter was a true son of the West. His years as a student at Maribyrnong High reinforced his love of its mix of established working-class Australian families and newly arrived immigrants, many of whom manned the factories of the west in the immediate post war years. Peter grew up in the family’s milk bar in Barkly Street, West Footscray, in the 1950s, and in one of his typical observations, he said that the succession of owners of the milk bar, Timorese, Vietnamese, and Sudanese, for instance, reflected the theatres of wars over recent decades ‘like clockwork’.

Peter succeeded Olwen Ford as the museum’s director when she retired in 1997. He managed over a hundred projects, supervised many exhibitions and community gatherings, wrote the book Your history Mate, explored the histories and industries of the West, and documented them in word and image augmented by intensive research.

But these are just figures. Peter was wholly aligned with the museum’s focus on local oral testimony and stories drawn from its industrial heartlands. He revelled in its ethos as Australia’s first eco-museum. And he brought on board indigenous storyteller, the late Robert Mate Mate, an initiated elder of the Woorabinda-Berigada people of Central Queensland, as a cultural officer; and Uncle Larry Walsh, Taungurrung man, as the Aboriginal liaison officer. Peter worked alongside them to document the ongoing presence of First Nations peoples in the West.

It was a partnership based on friendship and love. Peter shared with Mate Mate and Uncle Larry, and other First Nations’ elders, their sorrows and trauma over dispossession, whilst celebrating the epic grandeur of their ancient connection to, and knowledge of Country. Peter rejoiced in discovering that the Wurundjeri peoples remained a living, creative presence in the West. He worked closely on the Koori Gardening Team project, which began as a pilot training scheme employing young Aboriginal apprentices at the museum. It became the forerunner of other enterprises that have provided expertise and economic independence for many Aboriginal and Torres Islander peoples.

In those final weeks, as he held court in the front bedroom of his Footscray home, Peter proudly recalled the day in which the Karen people of Burma were welcomed by Wurundjeri elders. The Karen’s deep connection with the earth in their homeland compounded their sense of displacement as refugees in a new land. The day-long celebrations culminated in First Nation’s elders working alongside the Karen to plant bamboo in the museum’s garden.

Inspired by fellow visionary, First Nation’s elder, Reg Blow, this project, called ‘Custodian’s Welcome’, was emblematic of many projects Peter engaged in and reflected the way he saw the world. For years he championed the many cultures of the West. This is why the abbot sat by his bed on the day he died. Peter had worked with him and the Vietnamese community on various projects, creating for instance, an industrial grade worm farm, which recycles food scraps from the hundreds of free meals that are served in the Quang Minh temple every week.

One of Peter’s crowning achievements was the Volcano Dreaming project. Developed in collaboration with his partner Kerrie, and a team of community scientists and ecologists, it was a massive undertaking. The team created a vast panoramic montage, made up of over 3000 photographs taken in over 100 field trips, documenting the evolution of the wildflower grasslands of the western plains. Extending from Melbourne, across southern Victoria towards the border of South Australia, this fragile ancient ecosystem is under threat. Many plants and animals have already been driven to extinction since European occupation. Peter felt this personally. The western plains were an extension of himself, an intimate lived reality.

As too was his beloved block on Point Lonsdale. Again, Peter integrated his love of the area with practical activism. In 1999, he founded the Friends of Buckley Park to initiate projects aimed at protecting the coastal dune system between Point Lonsdale and Ocean Grove. He remained active as President until his final days.

Three weeks after his passing, hundreds of friends from many walks of life and backgrounds gathered at the Living Museum to celebrate Peter’s life. Uncle Larry Walsh performed a smoking ceremony. Friends, collaborators and family members spoke, long-time friend and cabaret artist Tim McKew performed Life is Just a Bowl of Cherries, and many attendees stayed on late into the night to recall Peter’s magic.

Peter’s playful, profound love of life ranged from the earth to the skies, and from the oceans to the great mysteries of the universe. It was a love that was grounded in family and community rituals. One of them was an annual New Year’s performance of Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat, staged on full moon nights every January by the Point Lonsdale lighthouse. The performances began 23 years ago, after the birth of daughter, Phoebe. The celebration of Peter’s life ended with a video of the final performance, filmed in January 2022, by torchlight on a mobile by Kerrie. Peter and Phoebe are pictured reciting the text in masks by the foreshore, silhouetted by the night sky. It is hauntingly beautiful.

On a Sunday morning, a month after Peter’s death, I drove to the Quang Minh Buddhist Temple in Braybrook. It is an oasis of beauty and community, located above the Maribyrnong, bordered by the factories of the industrial west. I lit incense for Peter and placed it at the feet of the giant white statue of the Goddess of Compassion, Guanyin. Wisps of clouds appeared to drift in and out of Guanyin’s sunlit profile. It was an image Peter would have loved. Backed by the vastness of the skies. Magical.

On the night of the full moon, 6 January this year, family and friends gathered on the Point Lonsdale foreshore beneath the lighthouse to honour Peter and his legacy. His partner Kerry and daughter Phoebe, wearing the masks, and accompanied by the audience, recited the Owl and the Pussycat. As the sun descended, they launched a homemade miniature boat loaded with cut outs of the owl and pussycat, and various offerings, setting it on fire as it swirled from the reef into the wind-driven currents. Farewell Peter.

Arnold Zable is a writer, novelist, storyteller and human rights advocate. His books include Jewels and Ashes, Café Scheherazade, Scraps of Heaven, Sea of Many Returns, The Fig Tree, Violin Lessons, and The Fighter. His most recent book, The Watermill, was published in March 2020.

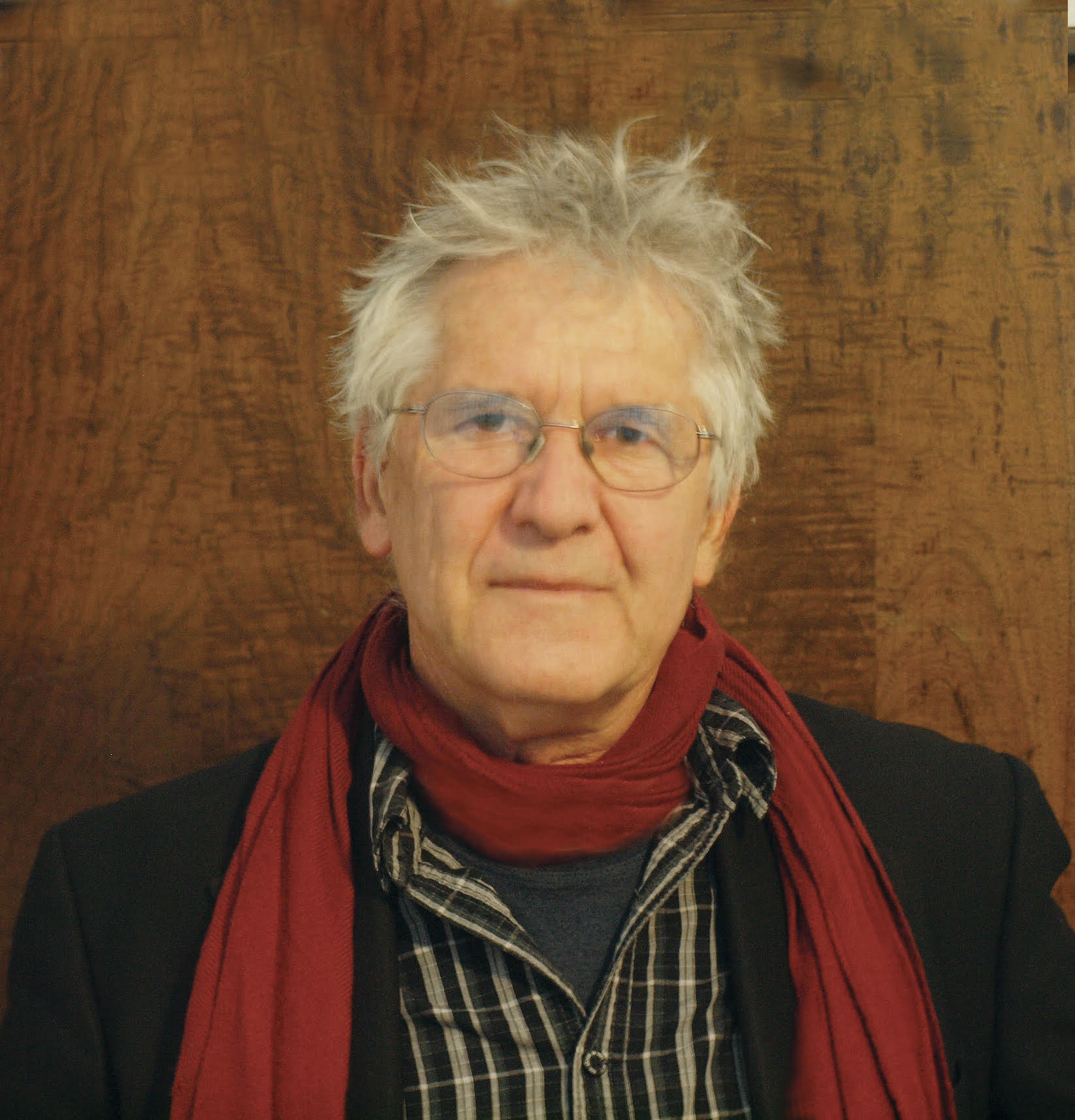

Main image: Peter Haffenden (Arnold Zable / Photo supplied)