Opening keynote address at the Catholic Mission conference Mission: one heart many voices 2017, Sydney, 15 May 2017

Let's start by giving thanks for the reconciling witness of Ginn Fourie. But also, let's admit that most of us who are parents would find it all but impossible to forgive any person who ordered the killing of one of our children. Ginn Fourie's story arrests us and inspires us because we know it is so out of the ordinary, and because we know that for us believers the forgiveness she found in her heart speaks of God's grace. She has forgiven the unforgivable. Ginn tells her story with a disarming humility. Imagine being in the same court room as three men who assassinated your daughter. Add to that the element of race. Ginn's daughter Lyndi had gone with friends deliberately to socialise in a multi-racial bar during the apartheid regime in South Africa. Lyndi, like Ginn, had dreamt of a more reconciled South Africa, a more just South Africa, a post-apartheid South Africa. Three young black South Africans had targeted this venue in revenge for the killing of black South African children by officers of the apartheid state. Ginn and Lyndi were South African citizens who would have abhorred those state killings done in their name.

Ginn attended the trial of the three young killers and gave the court interpreter a message: 'If they are guilty or feel guilty, I forgive them.' Though Ginn forgave them, it's important to note Ginn's precondition for forgiving them: 'I depended on the law to avenge my loss, and I was relieved when all three were convicted of murder and sent to prison for an average of 25 years each.' Mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation need not be invoked to bypass the truth and justice. Truth and justice may well be the most reliable path to mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation. A well-established legal order allows the state to administer justice to wrongdoers enhancing the prospect that their victims and the victim's families might then offer mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation. Consider the present situation of victims of child sexual abuse in the Church. Some of them might want to offer forgiveness to errant church officials and be able to seek reconciliation with the church community, but only once there is a legal regime or church arrangement in place for truth, justice and healing.

Ginn attended the trial of the three young killers and gave the court interpreter a message: 'If they are guilty or feel guilty, I forgive them.' Though Ginn forgave them, it's important to note Ginn's precondition for forgiving them: 'I depended on the law to avenge my loss, and I was relieved when all three were convicted of murder and sent to prison for an average of 25 years each.' Mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation need not be invoked to bypass the truth and justice. Truth and justice may well be the most reliable path to mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation. A well-established legal order allows the state to administer justice to wrongdoers enhancing the prospect that their victims and the victim's families might then offer mercy, forgiveness and reconciliation. Consider the present situation of victims of child sexual abuse in the Church. Some of them might want to offer forgiveness to errant church officials and be able to seek reconciliation with the church community, but only once there is a legal regime or church arrangement in place for truth, justice and healing.

Jane N. Dowling (a pseudonym for a self-described 'survivor' of abuse) has published a book Child, Arise! The Courage to Stand: A Spiritual Handbook for Survivors of Sexual Abuse. Jane hopes that 'survivors can discover that they are never alone because the loving God who created us and gave us life is with us in all the ups and downs of our healing journey.' Just look at the birds of the sky. They do not sow or reap or gather into barns. Think of the flowers growing in the fields. Not even Solomon in all his regalia was robed like one of these. Let's hope and pray for those victims who will never darken the door of a church again, that they will find healing and new life assured by their God that even if those to whom they were entrusted as children forget, they will never be forgotten and they can stand firm again knowing a rock, a stronghold and a fortress. Let's be ready to extend a helping hand to victims and church leaders. Both groups need our help; and both groups are yet to emerge from a very dark place. May God, our rock, our stronghold and our fortress sustain us in these dark days.

Three years after their trial and convictions, the three young murderers of Lyndi Fourie appeared before the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission where they had the opportunity to talk to Ginn. They thanked Ginn and said that they would take her message of forgiveness and hope to their communities and to their graves. But it was not until nine years after the death of Lyndi that Ginn encountered Letlapa Mphahlele, the mastermind of the massacre that killed Lyndi. Letlapa was publishing a book and Ginn attended the launch where she confronted him about his past crimes and asked him why he would not front the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He was remarkably honest with her, explaining that the commission, while overlooking the state authorised killing of blacks, would not acknowledge that he and his fellow rebels were engaged in a just struggle. He was anxious to meet Ginn after the book launch. She concluded 'that for Letlapa saying "sorry" is too easy. He wants to build bridges between our communities to bring conciliation'. Those of us with a commitment to mission and reconciliation need to have an eye to building bridges to those on the other side of the river of life, who are 'other'. And let's not forget that where you stand so often depends simply on where you sit. On what side of the river are you situated as you contemplate the divide between the 'haves' and the 'have nots', between the victims and the perpetrators of injustice?

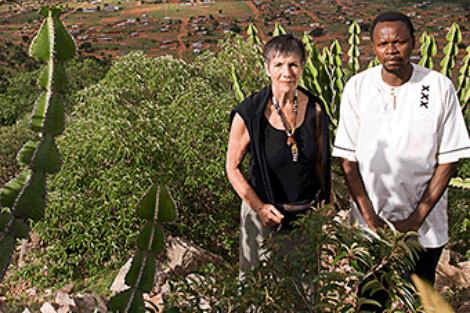

Ginn and Letlapa established a relationship of trust, committing to a better future for themselves and their country. Letlapa invited Ginn to his homecoming ceremony with his tribe. Ginn says, 'I was able to apologize to his people for the shame and humiliation which my ancestors had brought on them through slavery, colonialism and apartheid.' She then offers a profound insight: 'Vulnerable feelings, when expressed to other people, have the potential to establish lasting bonds.' The Australian journalist Martin Flanagan describes the event of that homecoming: 'Referring to Letlapa as a child of this soil, Ginn said: "I too am a child of this soil." She went on with wavering voice, "Your comrades' bullets killed my daughter. That terrible pain will always be with me. But I have forgiven the man who gave the command. I feel his humanity." She said she had consulted her ancestors who were deeply sorry for the shame and humiliation they had visited upon black people. Shame and humiliation lead to violence'.

Mind you, this sort of healing and reconciliation takes time. Ginn is honest enough to admit, 'If I'd met Letlapa in the first year after Lyndi's death, I would have tried to strangle him with my bare hands.' When visiting her 100-year-old mother on Lyndi's birthday, Ginn was taken aback when Lyndi's grandmother told her own daughter: 'You know that Lyndi was killed as a sacrifice for all us white South Africans.' Healing takes time; spiritual insight takes time. Our faith community should provide the space and time for this healing and insight.

The philosopher Jacques Derrida puts a clear challenge to us: 'Forgiving is surely not to call it quits, clear and discharged. Not oneself, not the other. This would be repeating evil, countersigning it, consecrating it, letting it be what it is, unalterable and identical to itself.' 'If one had to forgive only what is forgivable, even excusable, venial, as one says, or insignificant, then one would not forgive.' 'The forgiveness of the forgivable does not forgive anything: it is not forgivenes'. One must forgive 'the unforgivable that resists any process of transformation of me or of the other, that resists any alteration, any historical reconciliation that would change the conditions or the circumstances of judgment.'

Those of us who are Christian accept that there can be no reconciliation between us and God, and therefore no ultimate reconciliation in the ground of our being, except in and through Christ who forgave the unforgiveable through his life, death and resurrection. To quote Paul in his second letter to the Corinthians: 'It is all God's work; he reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation. I mean, God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself, not holding anyone's faults against them, but entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.' (2 Cor 5:18-19)

The reconciliation of this vertical relationship is possible only through the mediation of Jesus who embodies, lives and dies the reality of this reconciliation. He puts us right with our God and thereby establishes the basis for right relationship with each other. In many countries such as Australia, Timor Leste and South Africa, the public rhetoric and programs for reconciliation have, at least in part, been informed and underpinned by this theological perspective. Think back to the 1997 Australian Reconciliation Convention presided over by Patrick Dodson. Some onlookers of that convention twenty years ago observed that it had all the hallmarks of a Catholic liturgy. But, how can our theology of reconciliation assist the political process and outcomes in the public forum when there is no shared articulation of religious faith and no accessible fount of truth, justice and forgiveness? Those of the most profoundly humanitarian and humanist bent might profess profound commitment to truth and justice. But if forgiveness be the possibility of forgiving the unforgivable, it's hard to see how this can be reckoned or achieved in the secular public forum where an eye for an eye, and a fair go for all is as good as it gets. Forgiving the unforgivable can be done only through personal relationships as witnessed by Ginn Fourie or through communal sacramental celebrations.

The troubling question of how to attain atonement arises in Ian McEwan's novel of that name, Atonement. The main character Briony as a child wrongly accuses her older sister's boyfriend of a dreadful wrongdoing while he is visiting the family estate in the English countryside. Years later after he has wrongly served a term in prison, he then goes to war, escapes from Dunkirk and meets up again with Briony and the older sister. In the novel, Briony herself is an accomplished novelist and the last chapter consists of her ruminations about how to recount the tale and how to have it end. After publication of the book, McEwan confided that early in the writing project, he had read the initial chapters to his wife who then asked how it was all going to end. He started to improvise: 'I told her the last chapter and to my amazement she burst into tears. Ah, well, I thought, this is correct. I hadn't seen it in quite so emotional terms.' It was another two years before he wrote his final chapter but in terms almost identical with what he had described to his wife. In this closing chapter, Briony, the all controlling novelist within the novel, writes what McEwan had in mind those last two years:

The problem these fifty-nine years has been this: how can a novelist achieve atonement when, with her absolute power of deciding outcomes, she is also God? There is no one, no entity or higher form that she can appeal to, or be reconciled with, or that can forgive her. There is nothing outside her. In her imagination, she has set the limits and the terms. No atonement for God, or novelists, even if they are atheists. It was always an impossible task, and that was precisely the point. The attempt was all.

Originally McEwan had named his novel An Atonement but Oxford Professor Timothy Garton Ash on reading it 'had suggested that he remove the an, because the novel was not just about Briony's search for atonement but a more generic sense of redemption, about guilt as something "too great to expiate".'

Here we are, Catholics affirming our mission for reconciliation, affirming our belief that in Christ the unforgivable can be and is forgiven and that even the guilt which can be too great to expiate can be the occasion for redemption when together we 'know what we are, and can go on', immersed in the marketplace of politics, political correctness, conflict and avoidance, finding in ourselves and in our meeting of the other, the sacred meeting place of justice, truth, mercy and peace. To do this we need bridges across rivers and moments and places that bridge the gap of difference. Neither the victor nor the victim can set the limits and the terms. Together equally at risk, we might embrace the possibility of being and encountering the reconciler, the reconciled and the member of the reconciling community. Justice relates to the actions of the past, forgiveness to the present disposition of the wrongdoer, and reconciliation relates to the commitment of the parties agreeing to work together in the future. Pope Francis hinted at this in his meeting with the Lutherans in Sweden on the eve of the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther's 95 theses posted at Wittenberg. He told his Catholic and Lutheran listeners: 'For us Christians, it is a priority to go out and meet the outcasts and marginalised of our world. We Christians are called today to be active players in the revolution of tenderness.'

Ginn Fourie and Letlapa discovered something in common in their past. Together they jointly identified and acknowledged the injustices of the past of their country. Together they committed themselves to a joint project for the future on the path to reconciliation. United in the past and in the future, they could forgive and be forgiven the unforgivable in the present. Ginn could forgive Letlapa's unforgivable act of orchestrating the massacre that killed Lyndi. Letlapa could forgive the unforgivable acts of Ginn's ancestors who came and pillaged at will from generation to generation. We recall that there are Aboriginal Australians who have forgiven the unforgivable acts of past dispossession and violence, pictured graphically by those who wore the black T shirts saying simply THANKS on the day that Prime Minister Rudd delivered the national apology in the Australian Parliament.

Robert Schreiter who sadly cannot be with us has published a couple of books which are very helpful for us Christians committed to reconciliation and mission. In The Ministry of Reconciliation: Spirituality and Strategies, Schreiter rightly highlights that for those with a Protestant mind-set 'there is an emphasis on reconciliation as the result of Christ's atoning death and the justification by faith', but for those of us with a Catholic mind-set the focus is more 'on the love of God poured out upon us as the result of the reconciliation God has effected in Christ'. Celebrating the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther's posting of his 95 theses to Archbishop Albrecht, 'the most important churchman in all Germany, on 31 October 1517', it's probably time that we admitted that there is a bit of Catholic and a bit of Protestant in all us thinking Christians, or at least there ought to be. Schreiter lists five key points in Paul's teaching on reconciliation:

1. Reconciliation is the work of God, who initiates and completes in us reconciliation through Christ

2. Reconciliation is more a spirituality than a strategy

3. The experience of reconciliation makes of both victim and wrongdoer a new creation

4. The process of reconciliation that creates the new humanity is to be found in the story of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ

5. The process of reconciliation will be fulfilled only with the complete consummation of the world by God in Christ.

Schreiter has the great insight that the resurrection stories in the four gospels are stories of reconciliation. Through his own reflections on the resurrection accounts, he says 'we can bring our own stories of quests for reconciliation to the Jesus story.' In this way, he thinks that 'our quests might be illumined and our horizons expanded'.

We have all known loved ones who have died, and we are sure that their spirit lives on — perhaps in their children and grandchildren, and perhaps in their achievements and artistic productions. The disciples in the resurrection accounts would all have known such loved ones and they would have treasured those memories. But their experience of Jesus' resurrection is something altogether different, and so it is for us. That's why we turn up to Church proclaiming our belief in the Risen Jesus. This matters ultimately for each of us.

We remember that the disciples left Jesus in the last hours of the passion in a bad way. One of them betrayed him and went off and committed suicide. Those closest to him fell asleep when he was enduring his agony in the garden. The ever-assertive Peter went to water and denied him three times even after Jesus warned him that he would. Only one of them is reported to have been at the foot of the cross. But after the death and the strange happenings of Easter morning, Jesus was back with them as best of friends, breaking through the locked door in the upper room, telling them not to be afraid, and promising them peace during conflict, light in the midst of darkness. There he was forgiving the unforgivable.

We are told that Mary of Magdala came to the tomb early in the morning, while it was still dark. For John, the great story teller, dark is where we expect to find unbelief. Mary gets to the tomb and sees the stone rolled away. She rightly suspects that the body may well have been stolen. What other explanation could there be? John can dispel that theory by describing how the burial cloths were neatly wrapped, including the cloth over the face of Jesus. No thief rushing under cover of night would have gone to the trouble of unwrapping the body and folding the cloths neatly for future use. John expects us the listeners to recall that when Jesus responded to the call of Lazarus's sisters going to the tomb of Lazarus, he ordered that the stone be moved away and that the onlookers unbind Jesus and set him free. John goes to pains to tell us that there was a separate cloth to cover the face of Lazarus, just as there was a separate cloth to cover the face of Jesus. We know who moved the stone and who removed the cloths with Lazarus. They did it at the command of Jesus, for all to see. We enter the mystery of the stone and cloths being removed for Jesus. He was in no position to give a command. This could only be done by God, his Father, out of sight and in the mystery of grace.

Schreiter writes: 'A spirituality of reconciliation can be deepened by a meditation on the stories of the women and the tomb. These stories invite us to place inside them our experience of marginalisation, of being incapable of imagining a way out of a traumatic past, of dealing with the kinds of absence that traumas create. They invite us to let the light of the resurrection — a light that even the abyss cannot extinguish- penetrate those absences.'

There is then the sprint by Peter and the disciple whom Jesus loved. Peter sets out first, because that's what we expect of a leader. But the other disciple does not need any pope or bishop to show him the way to faith. He gets there first. He sees and he believes. We are coming out of the darkness into the light. Whatever the false and tardy steps of our church leaders (and there are many), we see and believe. Those leaders can affirm us in our faith. Unlike these two disciples in the Gospel, we have now understood the Scripture that Jesus had to rise from the dead. His rising from the dead is the definitive change in the relationship between God and creation, between God and us. We, like our loved ones before us, will all die. We will leave great memories and hopefully something of our spirit will be preserved by those who love and admire us. But that's not all there is. That is not the end for us or for them. We are assured continued life with God, and this is the source of our Easter joy. The Risen Jesus gives us something to live for, something to live by, and something to die for — the hope that all can be reconciled no matter how dreadful the history, no matter how deep the present mistrust.

At the moment in our world, we are immersed in the darkness of Syria, of North Korea, and the bombings in the Coptic Christian Churches in Egypt on Palm Sunday. But we see the light. We dare to hope for a better world to come. We dare to hope for the repair of our fractured human relations. Why? Because we too have rushed to the tomb and beheld not only the rolled back stone but also the neatly wrapped cloths which speak to us of the Risen Lord, the one who embodies the hope that we, and all we strive for, survive the grave and the remembrance of those who love and admire us. We, like Jesus, are invited into eternal life with our God who shows us the way, the truth, the light, and the life. It's our Easter faith that allows us to be ministers of reconciliation — holding the faith that beyond the grave is the possibility of justice and peace for all, and that on this side of the grave we are able to prepare for that kingdom to come and to effect its signs and presence breaking in here and now.

From time to time, I get to visit Georgetown University, a Jesuit university in the heart of American power, in Washington DC. Last month, the Jesuits and university administrators at Georgetown hosted a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope with about a hundred of the descendants of the 272 men, women and children who had been enslaved by the Jesuits and then sold in 1838, to pay off debts and keep the first US Catholic university afloat. The head of the Jesuits announced: 'Today the Society of Jesus, which helped to establish Georgetown University and whose leaders enslaved and mercilessly sold your ancestors, stands before you to say: We have greatly sinned, in our thoughts and in our words, in what we have done and in what we have failed to do. The Society of Jesus prays with you today because we have greatly sinned, and because we are profoundly sorry.'

Fr Kesicki, president of the Jesuit Conference of the USA, said, 'When we remember that together with those 272 souls we received the same sacraments; read the same Scriptures; said the same prayers; sang the same hymns; and praised the same God; how did we, the Society of Jesus, fail to see us all as one body in Christ? We betrayed the very name of Jesus for whom our least Society is named.'

At the mass celebrated the previous day, the Jesuit rector presiding at the liturgy prayed:

Justly aggrieved sisters and brothers: having acknowledged our sin and sorrow, having tendered an apology, we make bold to ask — on bended knee — forgiveness. Though we think it right and just to ask, we acknowledge that we have no right to it. Forgiveness is yours to bestow — only in your time and in your way.

These liturgical celebrations of reconciliation were the culmination of years of research and co-operation between the descendants of the slaves and the university administrators. They had agreed on a course of conduct trying to put right the sins of the past from this day forward. They agreed to providing the same preferential advantage in the university admissions process for the descendants as for the children of faculty, staff and alumni; renaming two buildings named after the Jesuits who arranged the slave sale; and creating an on-campus memorial to the slaves.

Building bridges of reconciliation is very painstaking work requiring practical and symbolic action. Pope Francis has given us all a lesson in bridge building with his visit last month to Egypt just weeks after the terrorist bombing of Christian churches there. In Cairo, he attended an international peace conference at the Al-Azhar Mosque and University with the grand imam Ahmed el-Tayeb. Pope Francis told the world:

Three basic areas, if properly linked to one another, can assist in dialogue: the duty to respect one's own identity and that of others, the courage to accept differences, and sincerity of intentions.

The duty to respect one's own identity and that of others, because true dialogue cannot be built on ambiguity or a willingness to sacrifice some good for the sake of pleasing others. The courage to accept differences, because those who are different, either culturally or religiously, should not be seen or treated as enemies, but rather welcomed as fellow-travellers, in the genuine conviction that the good of each resides in the good of all. Sincerity of intentions, because dialogue, as an authentic expression of our humanity, is not a strategy for achieving specific goals, but rather a path to truth, one that deserves to be undertaken patiently, to transform competition into cooperation.

In his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Francis writes: 'Frequently, we act as arbiters of grace rather than its facilitators. But the Church is not a tollhouse; it is the house of the Father, where there is a place for everyone, with all their problems.' More recently in Amoris Laetitia, he repeats the image of the field hospital and complements it with other images: 'The Church must accompany with attention and care the weakest of her children, who show signs of a wounded and troubled love, by restoring in them hope and confidence, like the beacon of a lighthouse in a port or a torch carried among the people to enlighten those who have lost their way or who are in the midst of a storm'. He then goes on to insist that mercy must be the hallmark of all we say and do: 'Mercy is the very foundation of the Church's life. All of her pastoral activity should be caught up in the tenderness which she shows to believers; nothing in her preaching and her witness to the world can be lacking in mercy.'

In Misericordiae Vultus when commencing last year's Year of Mercy, Francis noted, 'The temptation, on the one hand, to focus exclusively on justice made us forget that this is only the first, albeit necessary and indispensable step.' He calls us to move beyond justice to mercy, love and forgiveness. He knows that mercy is not a popular idea in present public discourse. He says that 'we must admit that the practice of mercy is waning in the wider culture. In some cases, the word seems to have dropped out of use. However, without a witness to mercy, life becomes fruitless and sterile, as if sequestered in a barren desert.' He compares God and man, mercy and justice:

If God limited himself to only justice, he would cease to be God, and would instead be like human beings who ask merely that the law be respected. But mere justice is not enough. Experience shows that an appeal to justice alone will result in its destruction. This is why God goes beyond justice with his mercy and forgiveness.

In my closing keynote, I will address A Mission of Justice and Mercy — Becoming a Church for Mission 2030. Meanwhile let's commit ourselves afresh to a mission of reconciliation, finding in our hearts the room for many voices, especially those voices which have been wronged and those voices which have perpetrated wrongs. The heart of Jesus has room for Ginn and Letlapa. We are called to be that beating heart for an unreconciled world.

Frank Brennan SJ is the CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia.

Frank Brennan SJ is the CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia.