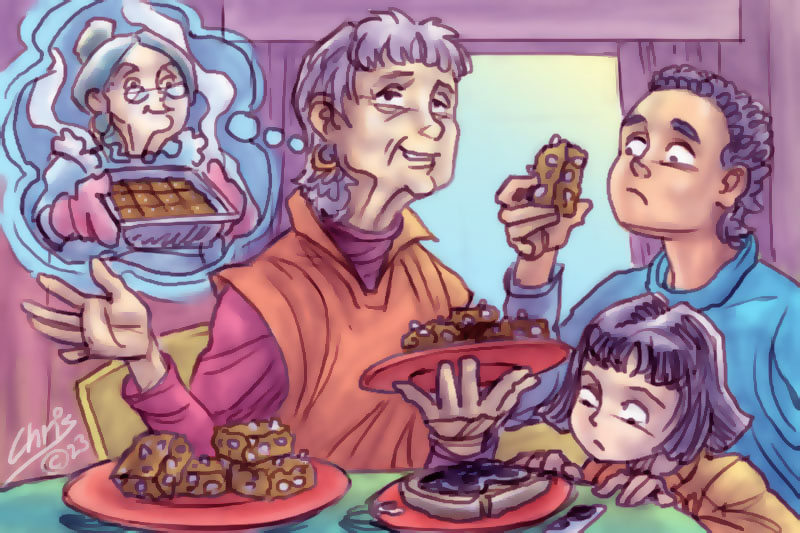

Greek waiters usually serve some complimentary sweet at the end of a meal. Often it is the cloying halva, or walnut cake dripping with honey. But last week, it was hedgehog! My English friends could not understand my nostalgic glee, so all I could do was try to explain that the chocolaty biscuit-studded slices took me straight back to childhood, even though they were not quite as good as the ones my Mum used to make: the biscuits could not have been Marie ones, for example. But these details didn’t matter.

Later those same details set off a train of thought about the food that I still miss, and the people who had made that food: of course I miss them more than I can say. Mum’s apple pies and her chocolate steamed puddings. The shepherd’s pie: it was my job to mince the leftover cold lamb in the little machine that screwed on to the edge of the kitchen table. Granny’s apple turnovers and her almond bars. Nana’s nut loaf and gingerbread.

Much later, when the woman who became my newly-widowed father’s second wife presented him with a jar of chutney, which was also one of Granny’s specialties, I was taught a lesson. Cook for a man the food he ate before the age of ten, said my worldly-wise friend Primrose, and you’ve caught him. I know a man, a mature English expat, who still literally walks for miles in order to sample another expat friend’s cauliflower cheese: the power of nursery food. He has never been caught, though.

When I return to Melbourne (all too seldom) I engage in a ritual. On the first day I make sure I eat fish and chips. A little later I buy at least one Cherry Ripe bar and a Violet Crumble. (I mourn the loss of the Polly Waffle, and so does Phillip Adams, who wrote a long-ago lament about its demise.) I’m proud of the fact that my Greek daughters-in-law are converts of years standing to these still extant and unique treats, but I admit to failure when it comes to the iconic Vegemite. My sons, having been heavily indoctrinated from an early age, quite like it, but all daughters-in-law say a firm OXI (NO.)

My Greek husband and my Austrian brother-in-law also gave a long-ago thumbs down to Vegemite, and to other mainstays of Australian cuisine as well. George could not believe the texture and the blandness of mashed potato, not to mention the lack of olive oil, and Karl was definitely anti-pumpkin. ‘At home,’ he intoned sternly, ‘we feed that stuff to the pigs.’ He was, naturally, never served pumpkin again. Of course when potato and pumpkin were mashed together, they emitted a stereophonic gasp of sheer horror. I realise now that they were helping us make a cultural transition: George cooked lamb stuffed with garlic, and Karl introduced us to sauerkraut and apple strudel.

The young must find it hard to grasp what things were like way back then, when Australia was largely populated by monocultural, monoglot carnivores. As far as I can remember the word lifestyle, if it existed, was rarely used. People didn’t know what the word meant or if they were in possession of such a thing. Exotic eating, a rare occurrence, meant a parcel of chicken with cashews from the local Chinese takeaway: I seem to remember you could bring your own saucepan. Although you could also ring your grocery order through to the relevant shop and await delivery, there was no possibility of ready meals appearing in the same way. The twin blights of McDonalds and Kentucky Fried Chicken had yet to descend upon the land. Vegetarians were few and far between, and were thought quite odd.

'Members of Sikh Volunteers Australia have become famous for feeding people in need, particularly during times of bushfire and Covid lockdown. At one stage they were providing 1800 vegetarian meals a day: many Sikhs involved regard this effort as part of their spiritual practice.'

How times have changed. Now, in multicultural Australia, different ethnic groups have altered both Australian eating habits in particular and society in general. And have done a great deal of good along the way. Members of Sikh Volunteers Australia, for example, have become famous for feeding people in need, particularly during times of bushfire and Covid lockdown. At one stage they were providing 1800 vegetarian meals a day: many Sikhs involved regard this effort as part of their spiritual practice.

A cookbook published by Melbourne’s Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC) captures this changed culinary landscape and the fusion of welcome, service and generosity the best meals inspire. The book’s title is Philoxenia, which translates as hospitality, or more literally friend to the stranger. Given members of at least six different nationalities at ASRC cook a variety of food daily, it points to that generous reception of guests and strangers, a practice of which Greeks are very proud.

Native American activist Winona LaDuke points out that food has culture, history, story and relationships. How right she is.

Gillian Bouras is an expatriate Australian writer who has written several books, stories and articles, many of them dealing with her experiences as an Australian woman in Greece.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.