The passing of Cardinal Pell on 10 January, 2023 occurred at a critical moment in the life of the Australian Church as its bishops consider how to respond to the call of Pope Francis in October 2021 for a synodal Church, based on communion, participation and mission. The news that he had penned an anonymous memorandum condemning the direction currently taken by the papacy appeared like a declaration of war against those he sees as enemies of the true Church.

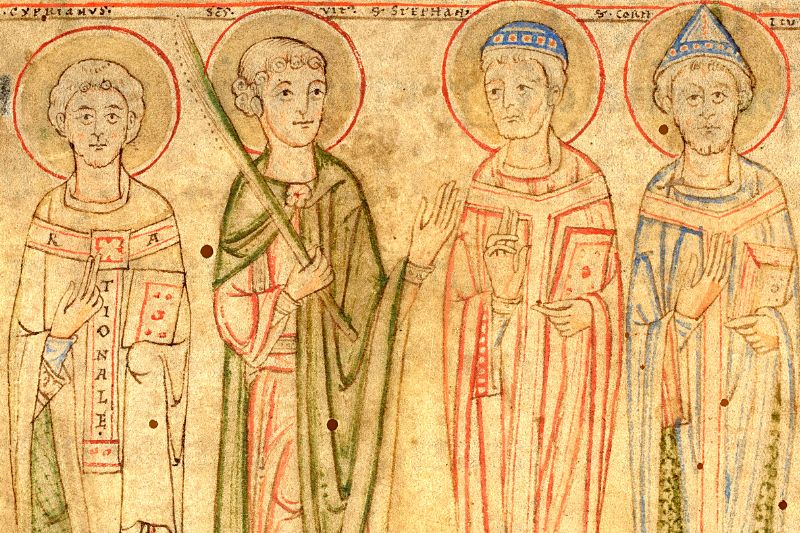

Yet synodality (literally travelling the road together) is simply another word for perhaps the oldest tradition in the Church, that of coming together to discern the voice of the Holy Spirit. Given that the Cardinal had a particular interest in the early Church (his doctoral thesis was on Cyprian of Carthage, a third-century Church Father), it is perhaps surprising that he did not reflect more on what Cyprian had to say about diversity within unity as like there being ‘many rays of the sun, but one light; and many branches of a tree, but one strength based in its tenacious root’.

The mechanism for resolving differences from the earliest days of the Church was that of the council, as attested by the account in Acts 6:1-6 about how the Twelve ‘called a full meeting of the disciples’, so that they might select those who could help distribute food to widows without incurring friction between Jews and Hellenists. While Acts names men appointed to this role, Paul makes clear in Romans 16:1 that they also appointed women, in particular Phoebe, a deaconess at Cenchrae. The emphasis in both Acts and in the Pauline Epistles is that decisions are made, not by bishops, but by the community as a whole.

Cyprian promoted the election to the papacy of Cornelius ‘by the testimony of almost all the clergy, by the suffrage of the people who were then present, and by the assembly of ancient priests and good men’. In emphasising that the bishop of Rome had the support of most of its Christian community, Cyprian rejected the claims of a rival pope, Novatian, who argued in favour of complete exclusion from communion of those who had lapsed from their faith during a period of particularly savage persecution. Cyprian favoured mercy and compassion for the sake of preserving unity within the Church.

These historical examples have great relevance to the contemporary Church — the need for appointing women as deacons, and of allowing divorced people and those who identify as LGBTQI+ to receive communion. Australian bishops (like those of any country) need to be aware that such policies are essential if the Church is to be perceived as listening to its oldest traditions. Yet in those early centuries, such traditions of consultation were inevitably shaped by the masculine paradigms of power within the Roman world.

Between the fourth and sixteenth centuries, Church Councils provided an authoritative structure through which doctrine and discipline were established. Prior to each council, it was common for a range of different interest groups to communicate their vision of what the council should establish. Articulate women, like Hildegard of Bingen, could use prophecy as a way of communicating their vision.

'One major challenge for those who call themselves Christian is to recognise the reality of the violence of sexual abuse and its lingering effects on those disillusioned by clerical failure to acknowledge these wrongs.'

The problem with such councils, however, is that they became hostage to episcopal privilege and national ambition. The first Vatican Council promoted papal supremacy. Only with the second Vatican Council was there a concerted effort to return to this conciliar way of thinking as involving the whole people of God. Only 23 women attended that Council, however, and then only as auditors.

Words get tired, and need to be reinvented, to recapture their original meaning. Synodality is simply the most recent way of regenerating traditions of consultation that go back to the earliest days of the Church. Here in Australia we can learn from how a multitude of First Peoples, each with their own language and songlines, their orally transmitted sacred traditions, have learned to live together in the same way as the branches of a tree, to use Cyprian’s metaphor.

The precedent for acknowledging diversity within catholic tradition must go back to the New Testament itself, in which (by the mid second century, and then not universally adopted) did a consensus begin to emerge of combining four versions of the Gospel and a range of letters from different apostles. Even then, the official record gives only the vaguest hints as to what female followers of Jesus had to say. Paul may have been shaped by the cultural assumptions of his day, but he did recognise that the message of the Gospel was for all people, whatever their status in society.

One major challenge for those who call themselves Christian is to recognise the reality of the violence of sexual abuse and its lingering effects on those disillusioned by clerical failure to acknowledge these wrongs. In the medieval period, it was thought that celibacy was a legitimate way of overcoming failures of chastity within a clerical elite. Such ideas operated within an understanding of sexual identity that privileged repression of the flesh. True synodality must involve recognition of those who have been abused by those in positions of power. The issues are not dissimilar to a debate within the national stage of acknowledging the voice of indigenous peoples within the constitution, and the violence to which they have been subjected over the last two centuries.

Whatever word we use for synodality, we must learn to travel together on the road.

Constant J Mews is Professor Emeritus at Monash University, attached to the School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies.

Main image: Saints Cyprian, Vitus, Stephan, and Cornelius, third quarter 12th century. (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC)