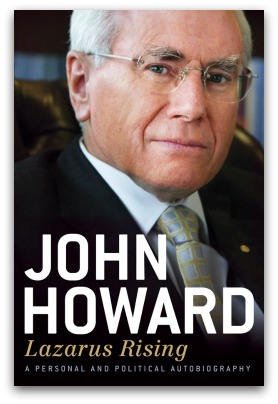

With no hint of regret or apology, former Prime Minister John Howard has defended his decision to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

With no hint of regret or apology, former Prime Minister John Howard has defended his decision to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In Lazarus Rising, Howard argues that the US Administration believed Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction that he could supply to terrorists. In other words, the decision was based on fear and supposition of what Saddam might do.

Howard writes that he relied heavily on intelligence reports that Iraq had such weapons, pillories opponents of the war and completely ignores the restraints of the just war principles.

As we know, that intelligence proved disastrously wrong. But why? Howard offers no explanation or even criticism of the failure.

Nor does he consider the devastating consequences of the war. Tens of thousands were killed in the invasion. According to the UNHCR, since 2003 two million people fled Iraq, 2.7 million more were internally displaced, and much of the country's infrastructure was reduced to ruins.

No one knows how many civilians have died as a result of the war since 2003; the Iraq Body Count puts the number at about 100,000, but other estimates put this much higher. To add insult to injury, the Howard Government later treated Iraqi refugees and asylum seekers very harshly.

The 'Coalition of the Willing' defied widespread forceful protests, including by key custodians of the just war principles, the churches. The Catholic Church firmly opposed the drift to war. Pope John Paul was strenuously outspoken, followed by all the major bishops' conferences throughout the world, including the United States. Many in other churches also challenged the morality of invading Iraq.

In addition, leading experts contested the case for war, including UN weapons inspectors Rolf Ekeus and later Hans Blix, as well as the retired chief of the Australian Defence Force, General Peter Gratian, and the former head of Australia's Joint Intelligence Organisations, Major-General Alan Stretton.

As Blix said in February 2003: 'The paradoxical thing is we don't really know whether there are weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.'

Before the invasion, the Australian Catholic Social Justice Council published a 56-page booklet, War on Iraq: is it just?, in which I summarised the case against going to war. There is not a word in this that I would now change. Relying on sources readily available in the media and on the web, how could this be so accurate and our intelligence agencies and government so appallingly wrong?

In particular, the so-called 'proofs' about Iraq's WMDs were exploded one after the other, including the mobile weapons factories and the aluminium tubes that were supposed to be for enriching uranium. This should have alerted Howard and President Bush about the weakness of the evidence, but they had already decided on war; the supposed weapons were a pretext.

In his account, Howard gives no consideration to the just war criteria. This is not surprising, as on all these principles the case for a just war fails.

Just cause. Despite Saddam's obfuscation, there was no clear evidence that Iraq possessed WMDs that posed an immediate threat. Much of the intelligence was faulty or overblown by the Bush Administration and its hawkish allies. Saddam had not supported terrorist attacks on the US, despite repeated US efforts to link him to them.

Last resort. Who can doubt now that it would have been better to have continued to contain Saddam rather than to invade Iraq? The invasion occurred for ideological and political reasons, not because there was no choice.

Legitimate authority. The legal status of the war is highly contested. The fact that only Britain and Australia joined the US invasion of Iraq, and that the United Nations refused to give its moral authority, undermines claims to legality.

Right intention. The Bush Administration claimed to be spreading democracy and human rights in Iraq, but questions arose about the Administration's close links with the oil industry and its desire to punish Saddam. As Howard wrote, Saddam was 'unfinished business'.

Proportionality and prospect of success. US neoconservatives imagined the invading forces would be welcomed as liberators. They refused to listen to warnings from experts in the State Department and elsewhere, or anticipate the difficulties in a post-war transition. It was part of Howard's responsibility to ensure such planning was done, and his book gives no indication that he took any steps to do so.

The Coalition flagrantly violated the principle of proportionality by destroying power stations, water purification works and communication networks. As a result, the population lacked clean water and essential services, resulting in a further huge death toll from hunger and disease. Why did the Australian government not use its leverage to urge greater restraint in bombing?

After nearly eight years, Iraq is still racked by sectarian strife and bombings. It lacks a stable government, and Iran has filled the regional power vacuum. As the churches feared, there has been an upsurge of anti-western sentiment in many Muslim countries, providing more recruits for terrorist networks. Of the ancient Chaldean Catholic Church, only 500,000 members, less than half the pre-war number, remain in Iraq.

In addition, the cost of the war keeps growing. The eminent US economist, Joseph Stiglitz, estimated it will finally cost the United States three trillion dollars, including for pensions and medical support for the many severely injured veterans.

Mr Howard abandoned the just war restraints developed by military, religious and philosophical thinkers over hundreds of years. He ignored completely the moral criteria for going to war, and instead plunged Australia into a 'war of choice'. One wonders if Mr Howard would have joined the invasion of Iraq had his middle name not been 'Winston'.

Dr Bruce Duncan is a Redemptorist priest and Director of the Yarra Institute for Religion and Social Policy at Box Hill. He specialises in just war and development studies at Yarra Theological Union.

Dr Bruce Duncan is a Redemptorist priest and Director of the Yarra Institute for Religion and Social Policy at Box Hill. He specialises in just war and development studies at Yarra Theological Union.