They came to stop the violence. Four, maybe five of them, in dark hooded jackets and pale, worn jeans. Hovering uncertainly in the car park. Shadow-like. Haunted.

They came to stop the violence. Four, maybe five of them, in dark hooded jackets and pale, worn jeans. Hovering uncertainly in the car park. Shadow-like. Haunted.

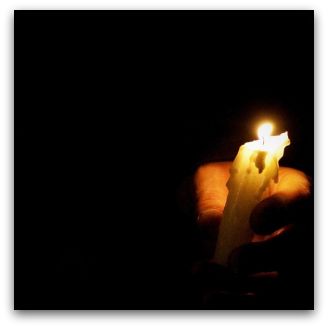

Wrongly, we assumed they had come to join us. It was 9.30pm, and we were gathered outside the place to which he had come, bleeding, begging for help. We had initiated this gathering: 'Bring a flower. Bring a candle. Spread the word. Spread the word.' And so with short notice we had gathered. With short notice, the word had spread.

Now, these newcomers. It was 'the media', angling for a statement, that had alerted them: 'How do you feel about the protests planned for outside Hungry Jack's tonight?' Not wishing for violence to answer violence, the small group of Indian students, who introduced themselves as the housemates and friends of Nitin Garg, had come to stop us.

Greg was the first to respond, with a pastor's face, wise to the inadequacy of words at times like these. Then Xingi, or was it Soph, with long stalks of white roses. Candles.

On the mutual ground of the restaurant car park we explained that we were simply people from the community. Christians, many of us. Concerned. Compelled. Our desire, like theirs, was for the violence to end. We asked them to join us.

A woman stood beside them as we waited for more people to gather. Students. Church people. Hungry Jack's workers. Local residents bearing straggly, home-grown flowers and arriving on bikes. Then we commenced the silent procession through Cruickshank Park, to mark the final steps Nitin took. We asked his friends to lead us.

Five days after Nitin's murder, the question of whether or not this violence was racially motivated rages on. People rush to defend Australia's reputation. Other stabbings, other murders, against all races of people, are cited. The Indian caste system is mentioned more than once.

Frantic pointing elsewhere. Everywhere except here.

Here at the grassroots, where, in the trembling, personal words of mourners, in the awkward shuffling of police officers' feet, in the slow weaving line of candles and the silent laying of flowers, people do care. Where Australians do grieve with the family of Nitin Garg.

Where, also, Indian students, away from friends and family, work grave yard shifts for minimum wages. Where they live poorly, in suburbs where rent is low, and catch public transport to work at night. Where one of their friends was stabbed on his way to work at Hungry Jack's.

Where together we gathered, joined in our desire to stop the violence.

Cara Munro organised a candle-lit prayer vigil on 4 January at the suburban Melbourne site of the murder of Inidan student Nitin Garg.

Cara is a registered nurse and passionate supporter of interfaith dialogue. Her essay 'Aurin' was awarded First Prize in the 2009 Margaret Dooley Awards.

Cara Munro organised a candle-lit prayer vigil on 4 January at the suburban Melbourne site of the murder of Inidan student Nitin Garg.

Cara is a registered nurse and passionate supporter of interfaith dialogue. Her essay 'Aurin' was awarded First Prize in the 2009 Margaret Dooley Awards.