Life lurches on in Greece. Moody's has lifted the country's credit rating marginally, but this will make no difference to your average Spiro and Maria, who face yet another hard winter. Troubles with the powers that be in Europe continue, unemployment rates remain high, young people are leaving the country in droves, and doctors and hospital staff are all set for another strike. Fascist Golden Dawn is still popular, and in the provinces the olive harvest, such a vital part of the rural economy and individual psychological wellbeing, has been disappointing.

Life lurches on in Greece. Moody's has lifted the country's credit rating marginally, but this will make no difference to your average Spiro and Maria, who face yet another hard winter. Troubles with the powers that be in Europe continue, unemployment rates remain high, young people are leaving the country in droves, and doctors and hospital staff are all set for another strike. Fascist Golden Dawn is still popular, and in the provinces the olive harvest, such a vital part of the rural economy and individual psychological wellbeing, has been disappointing.

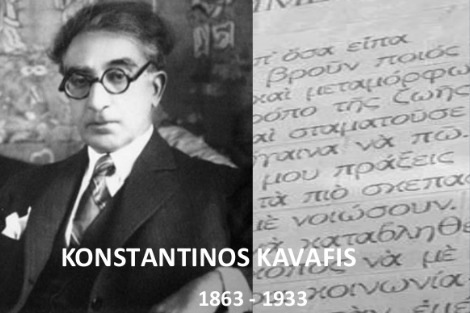

So it is cheering to have a little relief, along with a reminder that today's Greeks, like their forefathers, have a sense of rightness and proportion: 2013 has been declared the year of poet Konstantine Kavafis (anglicised as Constantine Cavafy). Like Shakespeare's, Kavafis' span displayed an unnatural symmetry, in that he died on his birthday. This year marks the 150th anniversary of his birth, and the 80th anniversary of his death.

I knew nothing about Kavafis until I came to Greece, but his presence in my mental and literary life is one of the many presents migration has given me. He was part of the cultivated Greek diaspora in Alexandria, where he spent most of his life working at his day jobs: those of journalist and civil servant. But in his creativity and spare time he was a relentless perfectionist who polished and reworked his 154 poems, which were read initially only by his friends: his fame came posthumously, and continues to increase.

Poets do not see it as their business to instruct, yet inevitably readers learn from them. When reading Kavafis' 'Voices', I learned once again about loss. 'Candles' teaches the reader about time and old age, 'Ithaka' about life's journey, and 'The City' about the patterns in living we seem doomed to repeat: no matter where we travel, we will return to the same metaphorical city and ruin our lives in exactly the same way we did at first.

Then there's 'Waiting for the Barbarians', possibly Kavafis' most famous poem. In it, citizens are doing nothing: they are waiting. The Senators are waiting for the Barbarians to come and make the laws, and the Emperor is also ready for their arrival. He is dressed and bejewelled, as are the consuls and praetors: all are ready to dazzle the Barbarians. The renowned public speakers, the rhetoricians, however, are silent, because the coming Barbarians are bored by such practices.

But suddenly confusion and restlessness begin, and the streets and squares soon empty. The Barbarians have not come, and word from the border says they no longer exist. The concluding couplet drives the lesson home:

And now, what will happen without the Barbarians?

These people were a kind of solution.

I cannot claim to think about Kavafis' poetry every day, but sometimes it connects with events or comments. Such was the case recently, when I read an online interview with Noam Chomsky, who asserts that America is a terrified country, but that much fear is of 'the concocted enemy'. He maintains that there are all sorts of things concocted for Americans to be frightened about, and points out that 'the whole terror system' is making enemies faster than it is killing suspects: he deplores both happenings.

Chomsky maintains that there is much distracting and scaremongering talk in America about the deficit, but that most people prefer to discuss the lack of jobs. Inevitably, he also comments on immigration: 'If you're worried about immigration, let's take a look at why people are coming, and what our responsibility is, and what we can do about it.' Taking a look is not usually a Greek response, and other countries, Australia included, seem to wear a variety of blinkers, or else turn a blind eye to the complexity of the problem.

The comments on the interview were mostly sane and sensible. One person said: 'No nation can ever be perfectly safe, so there will always be those who exploit insecurity.' Politicians mostly, it seems to me. Everywhere.

And there are those who will always try to escape responsibility. Kavafis knew it was, and is, often easier to sit around and wait for the Barbarians. But waiting cannot last forever, so then what?

Gillian Bouras is an Australian writer who has been based in Greece for 30 years. She has had nine books published. Her most recent is No Time For Dances. Her latest, Seeing and Believing, is appearing in instalments on her website.

Gillian Bouras is an Australian writer who has been based in Greece for 30 years. She has had nine books published. Her most recent is No Time For Dances. Her latest, Seeing and Believing, is appearing in instalments on her website.