So, the Government response to the Disability Royal Commission is in. The Royal Commission was billed as an opportunity (after plenty of previous reports), to get real government action on the multitude of issues facing those of us with disabilities: in the workplace, in school, in the justice system, in care and indeed, in everyday life. After months of harrowing testimony and ten months after the commission’s final report, of the 172 recommendations falling wholly or partially under the Federal Government’s purview, the government has fully accepted … thirteen (or just under 6 per cent). These included many reforms that were already partially in progress (such as reviewing the Disability Discrimination Act, continuing the Primary Care Enhancement Programme, improving the accessibility of complaints processes and providing data on unregistered providers). Disability advocates can, perhaps, be forgiven for being underwhelmed.

Government would not commit to a dedicated Disability Rights Act, setting out the rights of disabled people and effective enforcement of these rights. While it was prepared to consider some of this as part of the ongoing review of the possibility of a Human Rights Act more generally, it would not commit to more specific protections. Basic protections in line with international law (like those against involuntary sterilisation or the requirement to involve people in decisions made on their behalf) were likewise only ‘accepted in principle’, i.e. with no commitment to implement them.

The response to other areas was equally lacklustre. There was no commitment to raise subminimum wages, to end segregation in employment or housing or to agree an integrated set of principles for adult safeguarding – nor even to appoint a minister for disability issues. This, despite the fact that segregation from the broader community was cited by the Royal Commission as one of the biggest factors in violence against people with disabilities. The months of harrowing tales of such violence (which required incredible courage to recount) seems to have left the Government unmoved. Indeed, even the recommendation for a national agreement on reviews of deaths of disabled people was kicked into the long grass for ‘further consideration’.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that representative organisations issued a joint statement declaring that: ‘Today’s Federal, State and Territory government response to our four-and-a-half-year Disability Royal Commission is deeply disappointing and fails to respond to the scale of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability.’

Indeed, many people with disabilities had hoped for more from the Commission itself. While the stories it heard were horrendous, many similar tales had been told before – for example to the Senate committee which found – in 2015, no less – that violence against disabled people in institutional settings had reached ‘epidemic’ proportions. Many had hoped that the commission would be an opportunity not merely to tell these stories of horror again but to secure real, measurable and systemic change. It is now abundantly clear that the government has other ideas. Indeed, even the Government’s own Human Rights Commission said, in a media release: ‘Over four-and-a-half years, people with disability repeatedly provided harrowing evidence to the Royal Commission highlighting the inhuman treatment of people with disability. Sadly, it was not the first time our community had heard such accounts.’

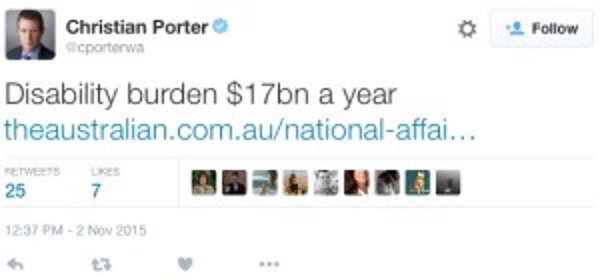

Indeed, the Government’s view of where disabled people sit in its list of priorities was on display again in the reforms to the NDIS currently wending their way through Parliament. The proposed changes, which aim to cut billions from the scheme, were enthusiastically endorsed by Pauline Hanson (who has previously described disabled people as a strain on teachers and schools). This government seems to share the view of disability pithily expressed by its predecessor:

In one area, however, the government does undoubtedly remain committed to disability. That, of course, is the funding to disable other people. The Government has announced that it is on track to grow Australia's defence industry to become a top ten global defence exporter by 2028. Together with AUKUS – which it seems, include the ability to receive radioactive waste from other countries – there seems little doubt that disability will be a growth industry for decades to come.

Fr Justin Glyn SJ, General Counsel of the Australian Province, was appointed by Pope Francis as consultor to the Dicastery of Laity, Family and Life.

Main image: (Disability RC)