I was once the fiction editor of a journal called Meanjin, a job that was far more for love than for money. Crates of short stories would arrive, and most would be returned without comment. There was only space to publish a small number. Once I was holidaying in NSW with my wife, Jenny, and was taken aback to find a sign in a café offering a support group for emerging writers who’d had their stories rejected by journals such as Meanjin ‘without a word of encouragement.’ I wished they knew it was only me at the other end.

I’ll not forget the day when a few very short stories stood out like diamonds in the slag heap. I rang the author, and we met for a coffee in North Caulfield. This was how I met Jacob Rosenberg and for five or six years until his death in 2006 he became a significant influence on my life.

Jacob grew up in the Polish city of Lodz, which became a ghetto in 1939. Later, he and his entire family, including two sisters, were deported to Auschwitz. All except one sister were murdered on arrival. The surviving sister took her own life within a few days. Imagine Jacob’s loneliness and despair.

Jacob had a childhood friend called Simcha. The two parted company when they were about fifteen because Simcha was committed to his faith and became a cantor in their synagogue. Jacob was drawn to politics and joined a socialist movement, “the bund”. One day, as he was falling in with a work party in Auschwitz, Jacob saw a truck loading with prisoners. On the truck, he saw Simcha. Before he could react, a guard approached Simcha and said, ‘I hear you’re a great singer. Well, I don’t want to hear you sing, “it’s a lovely day today”, I want to hear you sing, “it’s a lovely day to die”.’ In defiance, Simcha stood up and intoned the words sung between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, Avinu Malkenu. ‘God is our father and king.’ The guard shot him on the spot.

This was an important moment in Jacob’s existential journey, one which took him to the places of mystical depth which are reflected in his stories. After release, he went through displaced person’s camps where he met his wife, Esther, who had been in the Warsaw ghetto before being shuffled around eight separate camps. Eventually, they arrived in Melbourne in 1948. The couple had a daughter, and for a long time Jacob ran a tailor’s shop in Flinders Lane. He wrote Yiddish poetry and eventually switched to English, which was how we met.

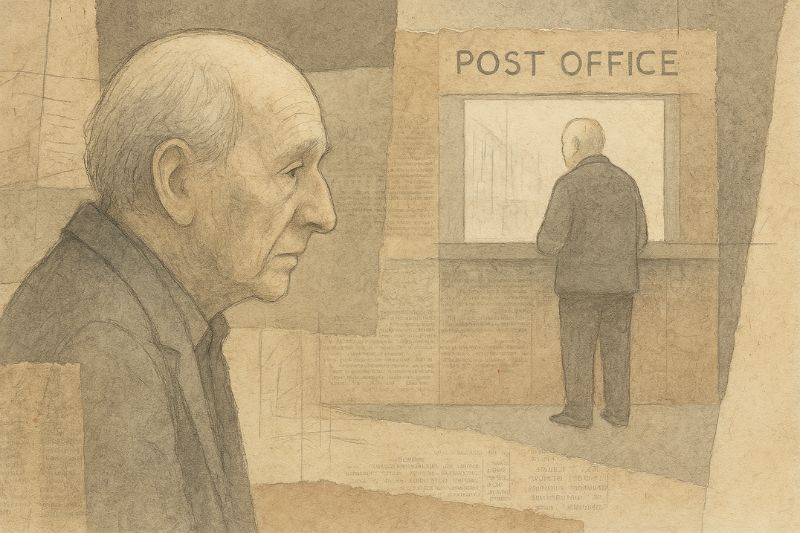

Jacob told me that one day late in 1948 he was in the Melbourne GPO when he saw the guard who had shot Simcha in cold blood.

I was stunned by what Jacob said. He had no doubt that this was the same guard.

‘How could I forget him?’ he asked.

‘So, what did you do?’

‘What could I do?’ he shrugged.

Jacob did nothing. He walked away.

‘Michael,’ he said, emphasising the point with his shoulders. ‘Somewhere it has to stop. Somewhere it has to end.’

I would offer Jacob’s words, somewhere it has to stop, to a world which is tearing itself apart. Peace only comes about when people are prepared to lose something. Peacemakers, Christ said, stand alongside those who mourn.

This year is unusual in that the great celebrations of Passover, Eid al-fitr and Easter fall in close proximity. If you drew a Venn diagram showing the intersection between these Jewish, Islamic and Christian feasts, there would also be a considerable amount of overlap. Of course, they all arise from different historical experiences and traditions. They express God’s mystery in different ways. But their historical experiences are centrally about faith in God that leads to peace, freedom, a fresh start and a belief in the sacred calling of all human people. They are all enlivened by a faith that does justice.

I am a Christian and, as Easter approaches, I am deeply pained by some of the appalling words that are sometimes put in the mouth of God, including by people who also call themselves Christian but with whom I feel precious little in common. It is patently absurd that some people, including Elon Musk, want to use Christianity as a political asset whilst claiming that empathy is somehow evil. You may as well look at the cross and argue that Jesus was the real killer. It’s crazy.

Antisemitism and islamophobia are both real and destructive. In Melbourne this past year, we have seen a beautiful synagogue set on fire and, on the other side of town, a woman attacked in broad daylight in a shopping centre. The attacker tried to strangle her with her own hijab. There is no point in barracking for one side or the other in any tension like this. I try not to never mention antisemitism without also mentioning islamophobia. It is a discipline I need to observe.

I am also deeply pained by increased spending on weapons of war. Around the world, a good deal of this money is coming from the pittance usually offered in aid to our sisters and brothers in desperate circumstances. How long will it take us to realise that there is no lasting peace without justice? One aspect of the Easter stories that speaks to me more and more is the fact that Jesus has no appetite for retribution. He doesn’t even mention Pilate or Caiaphas or Annas or the soldiers or any of the other proponents of hatred and violence. He is interested only in new life: love, healing and a fresh vision for the future. He knows, as did Jacob, that somewhere the anger and revenge must stop. That was the task the risen Jesus leaves to his followers.

Michael McGirr is the mission facilitator of Caritas Australia