In recent years dumping names and persons has become a cottage industry. In some cases ancestral names replace more recent ones. In other cases the current name is seen as objectionable. Generally, I have been unmoved by the debates – I can see arguments for and against. On hearing of a proposal to rename Deakin University, however, I found myself annoyed. But after more reading I saw the force of the proposal. I have a lot of time for Alfred Deakin, the second Australian Prime Minister who led the movement for federation. Deakin, however, also advocated both in Victorian and later in Federal parliament for policies based on racist theory which have wrecked the lives of Indigenous Australians. So what should the university do?

I believe that there are four principles to be taken into account. They pull in different directions. The first is that erecting statues and naming institutions are not private actions but reflect and reinforce the culture of a society. They represent the values that are honoured and the lives that are seen as admirable in society. These values will be reflected in the discriminations a society makes in is legislation and in public attitudes.

Second, naming and monument-making also record changes in culture and in what is valued. In Victoria the monument to Redmond Barry, the judge who had Ned Kelly hanged, is probably outnumbered by more modest representations of Ned Kelly. New statues of politicians, too, are less numerous than those of male sportspersons, and more recently of female athletes. Where that change in values is violent, as in the case of attitudes to such dictators as Stalin or Hitler, the pulling down of statues and renaming of towns that honoured them expresses revulsion at the past culture.

Third, where the attitudes and actions approved in a past culture discriminated against and and gave pain to particular groups in society, the descendants of those groups may continue to face discrimination. Where it is enshrined in the monuments and naming of the past, they may be a source of anxiety and outrage to the descendants. In colonial societies this explains the desire to remove monuments to people who killed and dispossessed Indigenous peoples, traded in slaves, and enriched themselves by dispossession. It is also expressed in the move to restore the Indigenous names for places significant to them.

Fourth, when we judge the past we ought to do so with humility. We may see clearly the faults and sins embedded in an earlier culture, but we are usually less aware of such failings in our own. The Scriptural axiom of leaving it to a person without sin to throw the first stone urges caution in destroying monuments, too. The corollary of this insight is that in telling the story of those whose names are enshrined in monuments and institutions we should include both their own virtues and vices and those of their culture. Our own monuments, too, should include representatives of people who suffered under and resisted the injustices of earlier generations.

This is to say that the politics of memory should make space for forgiveness just as should the politics of encounter. As with face-to-face forgiveness, the forgiveness of memory should include a necessarily vicarious public confession of guilt, a commitment to restore just relationships with the descendants of people who were disrespected, and in rare instances the penance of the loss of a monument or of institutional recognition.

'Deakin offers a university a rich inheritance, with humility thrown in. What equivalent heritage would disowning him leave? And which Australian in public life could safely be chosen to replace him?'

In light of these principles, what should institutions do with monuments to Alfred Deakin? First, they should unequivocally acknowledge that the ascription of moral and cultural superiority to the white race that underlay his policy on Indigenous Australians as well as his advocacy for the White Australia policy was and is abhorrent. It led to the separation of Indigenous families and the seizure of land on the basis of degrees of aboriginality. The continuing effects of these policies on Indigenous Australians make a reasonable case for institutions to dissociate themselves from his memory.

They should also take account, however, the context of his actions. In his time it was progressive wisdom to attribute moral qualities to race and to believe that inferior races would die out. The repulsive mixture of pity and callousness in Deakin’s reference to Indigenous Australians in his speech advocating the White Australian policy echoed the attitudes of other high minded contemporaries:

‘We have power to deal with people of any and every race within our borders, except the aboriginal inhabitants of the continent, who remain under the custody of the States. There is that single exception of a dying race; and if they be a dying race, let us hope that in their last hours they will be able to recognise not simply the justice, but the generosity of the treatment which the white race, who are dispossessing them and entering into their heritage, are according them.’

The progressive, self-congratulatory and brutal blindness in these lines are evident in retrospect. In any celebration of Deakin and of Federation they must be acknowledged and disowned. Deakin’s virtues and his public service, however, also deserve to be honoured, particularly by educational institutions. In his public life he displayed an intellectual curiosity honed by wide reading, was willing to engage with difficult questions, was prepared to engage patiently with premiers of other Australian States who had a far more parochial and self-interested view of Australia, and kept on seeking consensus. In insisting that Australia should be a Commonwealth, his vision embraced the more recent sense of the Commonwealth as a self-governing nation, but also with reference to its earlier ideal of a nation built on the pursuit of the common good. As a man of his time and class, of course, he saw this more idealistic and relational view to be embodied in Australia’s part in the British Empire.

.png)

Deakin’s qualities are precisely those that a university today should treasure as part of its patrimony – the sense of an intellectual tradition wider than the local, the view of a political understanding of nationality broader than one defined by exclusion, a belief that dialogue with people who hold different and even abhorrent views will serve truth, a commitment to public service, and the recognition that even the best of minds and cultures can often be cruelly wrong.

Deakin offers a university a rich inheritance, with humility thrown in. What equivalent heritage would disowning him leave? And which Australian in public life could safely be chosen to replace him?

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

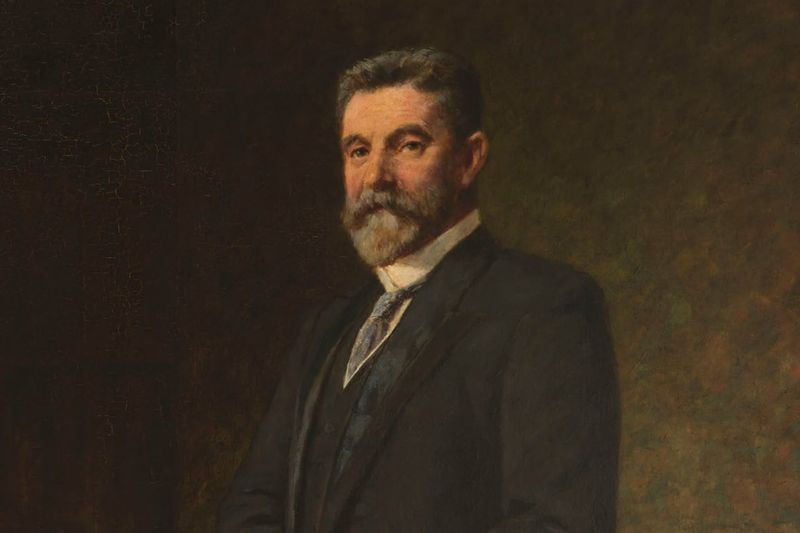

Main image: Official portrait of Alfred Deakin by Frederick McCubbin (Wikimedia commons)