'I love despair,' I said, and everyone laughed. But I do. As a concept. It's very important in the medieval literature I studied in my idle and misspent youth: 'Abandon hope all ye who enter here', written over the gateway of Dante's hell (I must pause here to tell you that I'm writing this with a speech recognition program that replaces Dante's hell with 'downtown hotel' — which may not be far off, if you think about all the alcohol and pokies and the consequent despair).

'I love despair,' I said, and everyone laughed. But I do. As a concept. It's very important in the medieval literature I studied in my idle and misspent youth: 'Abandon hope all ye who enter here', written over the gateway of Dante's hell (I must pause here to tell you that I'm writing this with a speech recognition program that replaces Dante's hell with 'downtown hotel' — which may not be far off, if you think about all the alcohol and pokies and the consequent despair).

St Thomas Aquinas thought hope the most important theological virtue because it inspired a man to do good actions. When he despaired, unrestrained, he fell into all kind of vices. Probably, this principle holds true for women as well.

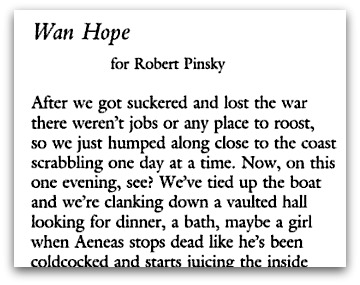

Despair's English name is wanhope. The death of a word is the death of an idea: wanhope has gone from our vocabulary, taking with it a palely loitering misery that's rather different from the modern black dog.

William Langland is the greatest exponent of wanhope. In Piers Plowman, he describes it as the cousin of sloth: a sort of vicious circle: you despair, you fall into sloth or accidie, you fall asleep, carelessly setting the house on fire, and fall into worse despair. Or the other way around: you're so slack that all your food 'forsloths in your service' and you despair.

I think of Langland every time I clear the mouldy cheese and sour milk from the back of the fridge.

But why am I writing about despair just before Christmas? Because I've forslothed on a deadline for three small articles for an Encyclopedia about how Biblical concepts fare in later literature: Despair, Damnation, and Capital Punishment are my Christmas fare this year.

In my research, I found a whole book about Victorian novels and the despair arising from the clash of ideals with reality: Catherine Earnshaw dying when she can't integrate Linton's civilisation and Heathcliff's energy; Maggie Tulliver dying because there's no place in a man's world for an intelligent, passionate woman; Dorothea Casaubon learning somehow to act in a narrower sphere and live to comfort others.

Despair's my old friend, and Damnation's always a kind of grisly fun — Dante's graphic representations of what sin does to the soul, Francesca whirled eternally in her lover's arms because she's subjected reason to desire, unable to take responsibility for her actions, blaming a book and its author instead.

Not so different from Charles Bukowski who envisages hell as an endless series of poetry readings with nothing to drink.

Then there are Milton's devils, ripping up hell's volcanoes to find enough gold to build their gorgeous palace of Pandemonium. Or A. D. Hope's Lord Byron, confined for his lust in a hell of women who offer sensuality rather than the 'sexless friendliness' of men — I think the sexism is Hope's.

Gallows humour aside, execution is no subject for joking; it's Christmas, and I'm reluctant to inflict capital punishment on you. Except to say that, during my research into literary executions, I was shocked to find so few cases where they were opposed on Christian grounds, and so many examples of Christian acceptance — Dr Johnson accepting that hanging was a reasonable fate for a forger and counselling Dr Dodds to think of his soul, Wordsworth's pietistic sonnets, Dickens romanticising the death of Sydney Carton and abhorring Fagin's horrible unrepentant despair rather than execution itself.

It seemed left to atheists like Shelley and Camus to oppose what Orwell terms 'The unspeakable wrongness ... of cutting a life short when it is in full tide'.

Most shocking was finding a collection of Irish Gallows Speeches in the second-hand bookshop. So many speeches of Christian repentance from condemned men who'd stolen some item of property, a 14-year-old boy holding himself up as a warning to other children, about to hang for stealing a grate. He can't have written this speech for himself. Some pious Christian must have done it for him.

Thank God, things have changed: in 1998, Pope John Paul's Christmas speech called for an end to the death penalty; Pope Benedict welcomed its abolition in Mexico, while conceding 'a legitimate diversity of opinion, even among Catholics, about waging war and applying the death penalty'; Eureka Street publishes Frank Brennan's speech opposing capital punishment altogether (though I can't find on the website any opposition to Iran's possible stoning of Sakineh Ashtiani — an affair which has aroused international condemnation through grassroots organisations Avaaz and Getup).

Perhaps I can banish wanhope and return to my Christmas reading of Antony Beevor's description of the hellish Stalingrad campaign, confident that we've made some progress and will make more, may save Sakineh and Scott Rush, and others languishing on death row. Happy New Year, Everyone.

Charlotte Clutterbuck lives in Canberra and writes essays and poetry. Her collection of poems, Soundings, was published by Five Islands Press in 1997. She won the Romanos the Melodist Prize for religious poetry in 2002 and the David Campbell Prize in 2009.

Charlotte Clutterbuck lives in Canberra and writes essays and poetry. Her collection of poems, Soundings, was published by Five Islands Press in 1997. She won the Romanos the Melodist Prize for religious poetry in 2002 and the David Campbell Prize in 2009.